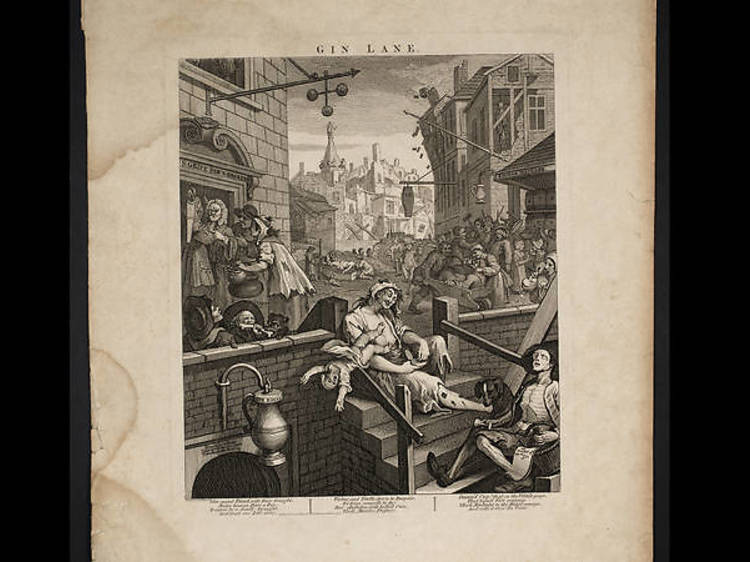

1. ‘Gin Lane’, 1751, by William Hogarth

‘This is the earliest work on show. Hogarth designed it as a print and produced it as a sort of humorous tragicomic image at a time when there was this national panic about alcoholism produced by a craze for gin, which had been imported originally from Holland, and therefore wasn’t “healthy” and “English” like beer. He produced “Gin Lane” and “Beer Street” at the same time. “Beer Street” is supposedly all about healthy drinking, whereas “Gin Lane” is about this evil that’s come over from the Continent. This was in the lead up to the Gin Act which, later in 1751, curtailed the number of unlicensed drinking establishments. Hogarth was moralising but he was a narrative artist as well. The whole thing is completely over the top, but it has to be to make its point.’