Right now, there’s trouble brewing in Stratford.

An unholy coterie of architects and developers are conspiring to bring a gigantic glowing globe to its streets. The MSG Sphere is a new concert venue that’s 110 metres high, and covered in over a million light emitting diodes that’ll either turn the night sky into a wondrous fairyland of glimmering adverts, or will be an obnoxious source of light pollution, depending on your point of view.

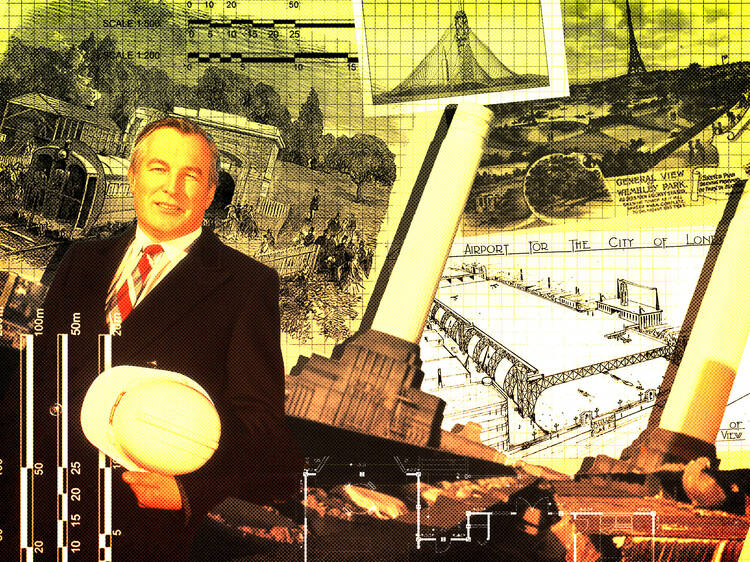

Thankfully for angry locals, there’s still one step before the MSG Sphere needs to go through: approval from Mayor Sadiq Khan. London’s skyline may be littered with unlovable, seemingly ill-conceived projects (the Walkie Talkie that fried cars, the eerie, James Bond villain-like Strata Tower, the Millennium Bridge that dangerously wobbled) but there are thousands more grand schemes that never made it off the drawing board. Here’s a timeline of some of the most weirdly brilliant buildings to never grace this city’s streets.

1820: The giant pyramid of death

19th century London was literally overflowing with corpses, with putrid results. You may have heard of Necropolis Railway, the Victorian train line designed purely to ferry dead bodies from overcrowded London to graveyards in Surrey. But morbid 19th century inventors nearly went one step further. Pragmatic architect/entrepreneur Thomas Wilson drew up plans for a modish Egyptian-inspired pyramid on Primrose Hill, a 94 storey high behemoth large enough to hold a frankly terrifying five-million bodies. Given that only two million people actually lived in London at the time, he was playing a long, long game. But sadly, the authorities decided it was preferable to build seven conventional cemeteries ringing the city (of which Highgate is probably the most famous). Boring!

1855: The crystal railway

In Victorian London, some people were starting to mutter darkly about putting trains in tunnels underground. What a bunch of freaks, am I right? Obviously, the correct solution to getting the city moving was to encircle it with a loop of trains that ran 24 feet above the city’s streets, and that was encased in a delicate carapace of steel and glass. This crystal railway was the brainchild of established architectural whizz Sir Joseph Paxton, who had already successfully designed London’s Crystal Palace (a lost exhibition centre that once sat in the neighbourhood of the same name). Even Prince Albert was on board. But sadly, the government declined to cough up the £34 million (in old money) needed to build it, leaving a motley patchwork of railway innovators to develop the London underground network we know and love to moan about today.

1890s: London’s very own Eiffel Tower

Remember the insults heaped on the creators of Marble Arch’s Mound? Well, they were nothing compared to the shame that befell ambitious Victorian entrepreneur Sir Edward Watkins. His generous attempt to build London its very own Eiffel Tower in Wembley got nicknamed ‘shareholder’s dismay’ or ‘Watkin’s folly’ after the half-built structure started to sink into the marshy ground it was constructed on. He died in 1901, and what was left of the tower was torn down the year afterwards. Its foundations were rediscovered in 2002, when Wembley Stadium was being rebuilt. Imagine if Wembley was best known as a romantic picnic spot, and not Jadon Sancho and Bukayo Saka missing back-to-back penalties?

1934: The airport right in the middle of central London

No, I don’t mean central like City Airport. I mean really, really central. As in, sitting on a raised platform right in front of the Houses of Parliament central. In the ’30s aeroplanes were comparatively dinky so this suggestion wasn’t as nuts as it might be today…except for the fact that the rate of plane crashes was substantially higher. One wrong move from the pilot could have wiped out an entire nation’s politicians and left Britain’s inhabitants to return to the olden days of self-governing communities and bartering. Oops!

1960s: The Regent Street monorail

The main thrill to be had on Regent Street these days comes from taunting the costumed characters that cavort outside Hamleys. But it was nearly a much more exciting place to be. In 1967, the Conservative Political Centre published a plan for a monorail that would glide high above the traffic, replacing the boring old buses at ground level. In what’s frequently been described as the best ever episode of The Simpsons an ill-conceived monorail turns Springfield into a flaming wasteland. I guess it’s a good thing we’ve avoided that fate… but imagine how exciting it would be to soar right through the middle of Regent Street’s Christmas lights, watching the shoppers scurry like ants through the streets below.

1980s: The Martian space centre

Back in the ’80s, sociologist and Labour ideas man Lord Michael Young got surprisingly far with his plans to create a giant space centre on Southbank, where volunteers would live in an experimental Mars-ready community while their experiences were broadcast on national TV. NASA scientists got on board, Young agreed a deal to buy Bankside power station, and designs were drawn up for a giant tower and artfully designed biodome. Annoyingly, the government stepped in to keep the site in public ownership. A small setback for space research and a much bigger setback for London’s fame-seekers, who had to wait another decade to apply to be on Big Brother.

1989: The Battersea Power Station theme park

While Battersea Power Station slumbered, its cavernous interior sheltering only pigeons and gently toxic waste, property developer John Broome was dreaming up plans for it that would blow memories of his previous big project Alton Towers into the stratosphere. It would house an indoor theme park. One with four vast rollercoasters, the world’s largest aquarium, 4D cinemas, towering waterfalls and peaceful botanic gardens. Broome’s office would be in a glass bubble at the building’s highest point, overseeing the mayhem like a spider on its web. It all sounds like an impossible dream, but actually, work was well underway before its engineers discovered the building was structurally unsound and riddled with asbestos. The recession was the final nail in the coffin for the dream of a theme park for Southbank. Recreate the magic by getting jacked up on caffeine and riding up and down the escalators in the sensible, shiny shopping centre that now fills Battersea Power Station. It’s almost as much fun.

2016: The Garden Bridge

An astonishing £43 million of public money was spent on plans for this Thames crossing, the idea for which was first floated at some point in the ’90s by Joanna Lumley, before it inexplicably became a prime government priority in the 2010s. Yup, trees are nice. But not even the then-Mayor Boris Johnson could come up for a compelling reason for dropping hundreds of millions on this elaborate, plant-decked river crossing. When asked, he said he “wasn’t really sure what it was for”, but that it would make a “wonderful environment for a crafty cigarette or a romantic assignation”. Eventually, plans for London’s Garden, Sex and Ciggies Bridge were scrapped for being a bit of a waste of money, leaving people with only public parks to misbehave in.

But as pointless as this project might have been, it also feels like a poignant reminder of a more optimistic, more prosperous era, one where imagination came first and practicality trailed far behind, like a plodding bus following in the wake of a lightning-fast (but ultimately impractical) monorail.