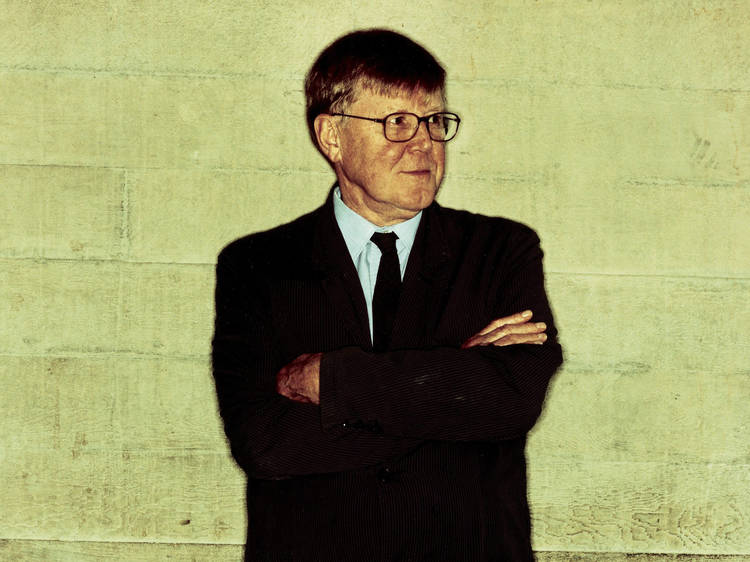

Only, he’s not. He’s Alex Jennings, the actor playing Bennett in ‘Untold Stories’, a double-bill of autobiographical plays based on the writer’s childhood memories. He’s a bit more upright than the 79-year-old and a bit younger, but otherwise it’s uncanny – right down to the pursed-lipped smile. At early performances, Jennings says he stepped out to a chorus of gasps.

An hour before curtain up, sat in his dressing room, Jennings lets slip he’s had some practice: ‘A friend of mine said, “You’ve been pretending to be Alan Bennett in the kitchen for 20 years. Now you get the chance to earn money doing it.”’

Face it, we’ve all had a go at that lukewarm West Riding accent. It’s the soundtrack to a thousand childhood car trips: Bennett reading ‘The Wind in the Willows’ or ‘Winnie the Pooh’ in his very own, very Droopy-the-Dog drawl. More than any living writer, Bennett inspires affection, if not outright devotion, in audiences. Who else could sell out the National with two plays about himself, then transfer them to the West End? It seems we can’t get enough Bennett-on-Bennett action.

We’ve loved him ever since he waltzed up to Edinburgh with ‘Beyond the Fringe’ in 1960 and casually revolutionised comedy overnight. As you do. Aged 26. We admired Peter Cook and we liked Dudley Moore; we didn’t really know what Jonathan Miller was on about, but Bennett we loved. (Even ‘Spitting Image’ let him off lightly, routinely showing a tiny Alan having tea and a natter with Thora Hird.) And he hasn’t really changed since. ‘He’s found a look and stuck with it,’ says ‘Untold Stories’ designer Bob Crowley, ‘so now it’s part of his personality. There’s nothing ostentatious about him and, for that reason, I’d call him a style icon.’ Then, there’s Bennett’s writing: a string of modern stage classics: ‘The Madness of King George III’, ‘Forty Years On’ and, best-loved by far, ‘The History Boys’. Plus, short stories, essays, documentaries and television dramas. ‘It was classy stuff,’ says Jennings. ‘The sort that doesn’t get made now, but he was also pushing boundaries. No one had seen anything like “Talking Heads” before. The detail of his observation is extraordinary.’

And that’s the key. Brits get Bennett because Bennett gets Brits. He sees through our outward politeness and exposes the quirks and insecurities. Never nastily, mind; always with a wry chuckle. His is a lost, better Britain; one of cod liver oil and cathedrals, before Murdoch and the metric system. For all that he pooh-poohs the term, Bennett is a bona-fide national treasure.

‘Oh, he hates that,’ warns Jennings. ‘There’s a public perception of him being little and cuddly – like a mole, I suppose, or Pooh Bear – but he’s not like that at all. He’s sharp.’

Particularly sharp with journalists, as it happens. Bennett stopped giving interviews in 1993, after The New Yorker speculated about his love life. Shortly afterwards, trapped at home by reporters, he wrote in his diary, ‘All you need to do if you want the nation’s press camped on your doorstep is say you once had a wank in 1947.’

His elusiveness isn’t confined to hacks. Ian McKellen once asked whether he was gay or straight. ‘That’s a bit like asking a man crawling across a desert whether he would prefer Perrier or Malvern water,’ Bennett replied. A combination of shyness, modesty and crotchety reticence – such quintessentially British traits that, ironically, only endear him to us the more – mean we actually know very little of Bennett.

To that end, Jennings’s dressing room is scattered with Bennett paraphernalia: collected plays, portrait postcards, a four-disc box set of ‘Alan Bennett at the BBC’, two of the writer’s own ties. There’s something disconcerting about it – a hint of the stalker’s lair, perhaps. Jennings has been trying to get under the surface: ‘One flatters oneself that it’s not just an impersonation – that there’s something else to it. I don’t know what, but it’s not just Rory Bremner.’

Bennett himself has been closely involved in the production, acting as a kind of mentor to Jennings. So how does the real Bennett compare to the one on stage? ‘He kept telling me to be nastier, to be meaner,’ Jennings reveals. ‘I can’t let it tip into cups of tea and digestive biscuits.’ Bennett also had one costume note for Crowley: the jumper needed some food stains. I want to get closer to Bennett myself. He doesn’t often do journalists, although he’s thawed a bit in recent years, but acquiesces – via an intermediary – to an email interview. Eight questions receive all of 254 increasingly terse words in reply. He refuses to be photographed. Oh, and he really does hate the ‘national treasure’ thing. ‘It’s cosy and I don’t like labels,’ his message says. Bennett has been more open to self-revelation in recent years, publishing two books of diaries, memoirs and essays, and writing himself into plays. This newfound openness came after he was diagnosed with bowel cancer. He had chemotherapy, and recovered, which he touches on in ‘Untold Stories’. ‘You could call it tidying up,’ he says. Yet the onstage Bennett is still only a version deemed safe for public consumption. ‘Very little of my own life is revealed,’ he wrote of ‘The Lady in the Van’, which also sees two Alan Bennetts – the writer and the man – bicker about what to do with the woman who has lived in a vehicle in his driveway for a decade.

The stage Bennett and the real Bennett once really did collide. When an actor missed a performance of ‘The Lady in the Van’, Bennett stepped into his own shoes. ‘I only played myself once,’ he tells me, ‘and I didn’t feel in the least bit convincing. It’s both easier and harder to write about myself – or a character based on myself. Easier, because the audience probably knows something about me already, so I don’t, as it were, have to spell myself out. Harder, too, for exactly the same reason: if they think they know what I’m like, it’s harder for me to outflank what they already know.’

Bennett’s dramas are full of similar inversions: treacherous spies have their virtues; inspiring teachers and poets have their flaws. Is this the writer challenging his own reputation? ‘The character on stage is probably less sympathetic than the one in my diaries,’ he types. ‘Being embarrassed by one’s parents is not particularly commendable – though it’s not uncustomary.’ Evidently even Bennett’s published diaries don’t show us the real man.

So what do we know about the real Alan Bennett? Apparently, he never crosses his legs. There you go. That’s the best scoop I’ve got. I can’t even prove those are his words, because our email Q&A went through a third party. For all I know, it’s Jennings getting into character. But, with this Bennett double-bill now transferring to the West End, it seems we’re happy to take whatever we can get of this reluctant, half-buried man.

Back in Jennings’s dressing room, his hair has been combed into Bennett’s side parting. He gives it a little ruffle and purses his lips. ‘Then you put on the glasses and… Alan Bennett.’

Discover Time Out original video