[category]

[title]

Founder Tommy Gelinas has been saving Valley-centric vanishing architecture and keepsakes for over two decades.

“This is like my childhood in a nutshell,” Valley Relics Museum founder Tommy Gelinas says as we survey a display of Southern California fast food curios. Between a wooden Taco Bell sign and an oil painting of Colonel Sanders, there’s a Jack in the Box clown head that you used to be able to yell your drive-through order into—at least until “the clowns might’ve freaked out one too many kids so in the late ’70s, early ’80s they started blowing up Jack [in TV commercials].”

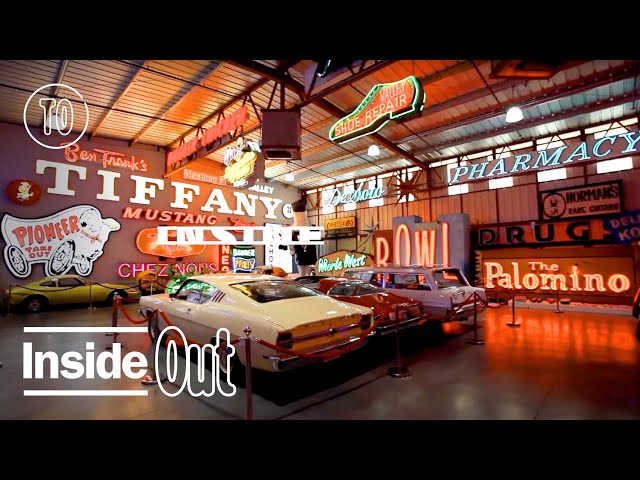

If there’s a 20th-century local pop culture curiosity that’s vanished from L.A.’s San Fernando Valley, there’s a good chance some remaining shred of it has found a second life at this Lake Balboa museum. Gelinas has been rescuing, collecting and preserving Valley-related ephemera for over two decades. In 2013, he first put his accumulation of mementos on display at the Valley Relics Museum’s first brick-and-mortar location in Chatsworth. As his collection of 20-foot-tall signs grew, he moved the museum in 2018 to its current home, a pair of spacious hangars at the Van Nuys Airport stuffed with cars, bikes, neon, arcade cabinets and celebrity memorabilia.

For out-of-towners and Basin-dwelling Angelenos, the Valley’s reputation has often been unfairly distilled down to a few things: heat, adult entertainment and, like, grody-sounding Valspeak. For Gelinas, though, growing up in the Valley was so much more than that. It was go-karts and BMX tracks, record stores and themed restaurants, film studios and movie star residents, hot rods and airplanes, and sparkling swimming pools alongside empty ones that’d been converted into skateparks. But there wasn’t really any sort of shrine to that story of the Valley.

“I always tell people, it’s not Van Gogh,” Gelinas says. “The Valley’s history is really important history, it’s very interesting history. But no one’s really fighting for it.”

Now, though, the Valley Relics Museum sure is. Unlike a Post-Impressionist masterpiece, its acquisition and authentication process tends to be a bit more straightforward. A lot of the items that enter into the museum’s collection are donated, many times from celebrities’ and business owners’ surviving family members. The rest are rescued. In those cases, there’s a pretty good chance the museum already has postcards and photos to document the history of the item, and oftentimes Gelinas is scooping up the artifacts himself.

“I pretty much have saved every item personally by hand,” he says. “And when something’s donated, it takes time and money to hire a crane and bring a crew down. Anyone can take down a sign for a few hundred bucks. But just anyone can actually carefully remove the neon, bring the sign down, transport it, get it safe and then restore it.”

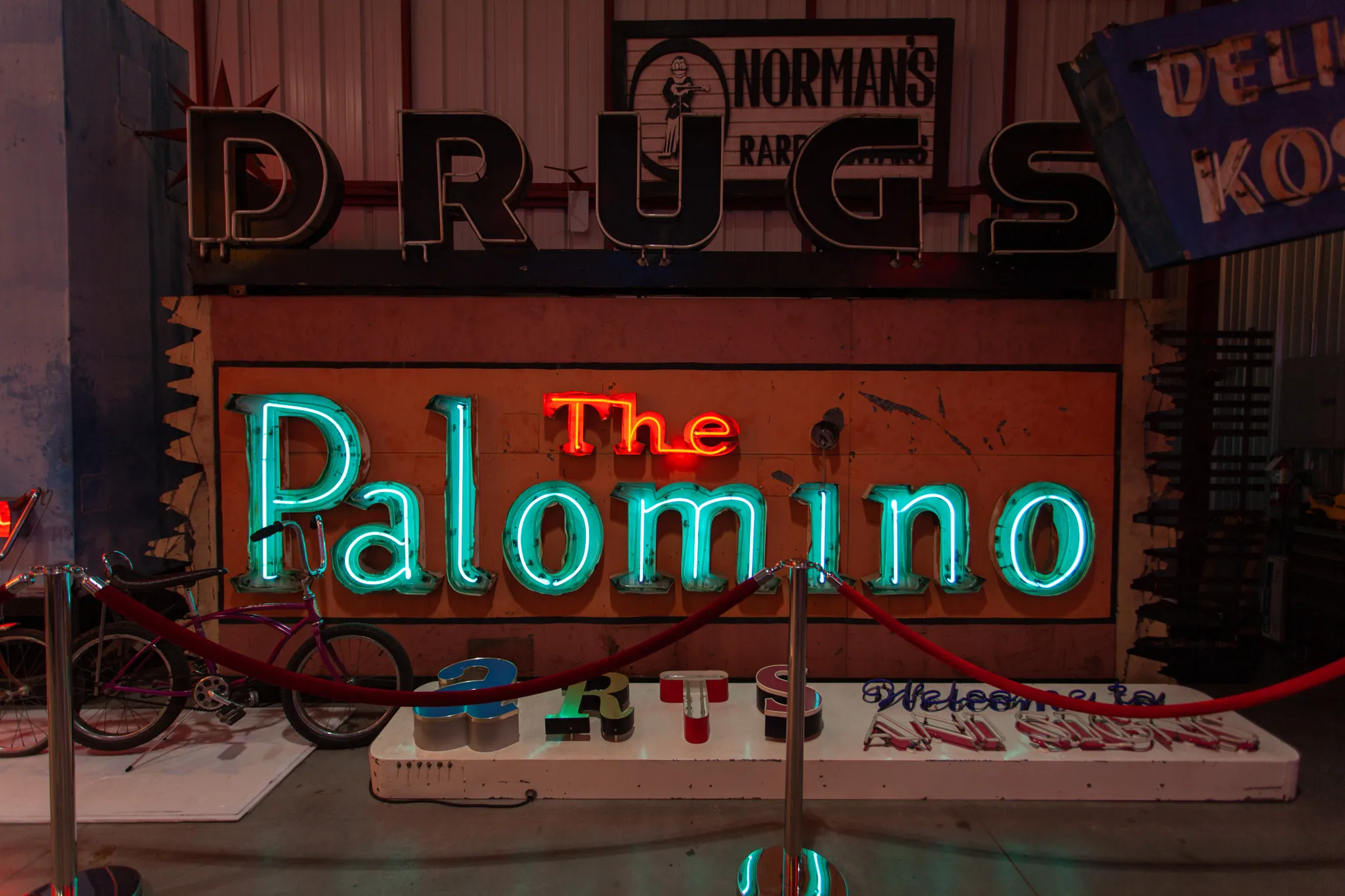

The museum’s hangar full of illuminated signage is easily its most visually impressive asset. You’ll find insignias from some familiar spots like Henry’s Tacos and Bob’s Big Boy, but the neon and backlit collection is mostly a collection of Valley bygones: country western club the Palomino, mostly-vanished fast food chain Pioneer Chicken and Woodland Hills spot My Brother’s Bar-B-Q (three-dimensional cow sign included).

For a long time, the Valley was looked down upon because people didn’t understand it

It’s also where the museum deviates the most from its geographic boundaries and acts as a catch-all for dying signage around the city, like the starburst-adorned Premiere Lanes from Santa Fe Springs or the Sunset Strip’s former Tiffany Theater and Ben Frank’s. When we met with Gelinas this fall, we happened to bring up the Pig ‘N Whistle sign in Hollywood that had been abruptly dismantled the day before. Sure enough, Gelinas started swiping through photos on his phone: His team had already saved the neon letters and carefully placed them into the bed of a pickup truck.

Beyond the monument to business marquees, you’ll find rows upon rows of nostalgic souvenirs. BMX bikes from manufacturers like Redline and Mongoose—that were made in the Valley, where the sport first took off in the ‘70s—are suspended from the ceiling. There are signs and blueprints from Lockheed’s secretive Skunk Works aerospace plant in Sun Valley. Still-functioning cabinets from Family Fun Arcade in Granada Hills are set to free play. There’s a cash register and belt buckles from cowboy-bedazzler Nudie Cohn’s North Hollywood shop, plus his antler and spur-adorned Pontiac. Spicoli’s Volkswagen bus from Fast Times at Ridgemont High is currently on display on a yearlong loan, complete with its interior disco ball.

Like any proper museum, there’s a gift shop, too, and here Valley Relics has taken the clever step of letting you literally buy a piece of nostalgia. Gelinas scooped up the rights to dozens of defunct local restaurant and retail logos, so you can support the nonprofit by buying a T-shirt with Malibu Grand Prix’s F1-style go kart against the sunset or Licorice Pizza’s steaming record. Taken altogether, it’s a pretty persuasive argument that the Valley has offered way more than just sleepy suburbia.

“For a long time, the Valley was looked down upon because people didn’t understand it,” Gelinas says. “But every time someone talked funny about the Valley, we were like, it doesn’t really matter, because there was so much to do.”

The Valley Relics Museum is located at 7900 Balboa Boulevard in hangars C3 and 4 (you’ll find the entrance on Stagg Street). It’s open Saturdays and Sundays from 11am to 4pm. Admission costs $15.

Discover Time Out original video