Robert Longo interview: “The shows represent what we thought we could be versus what we are right now”

The artist offers competing visions of America in two gallery shows

How did the exhibitions come about? Why did you pair these sets of images?

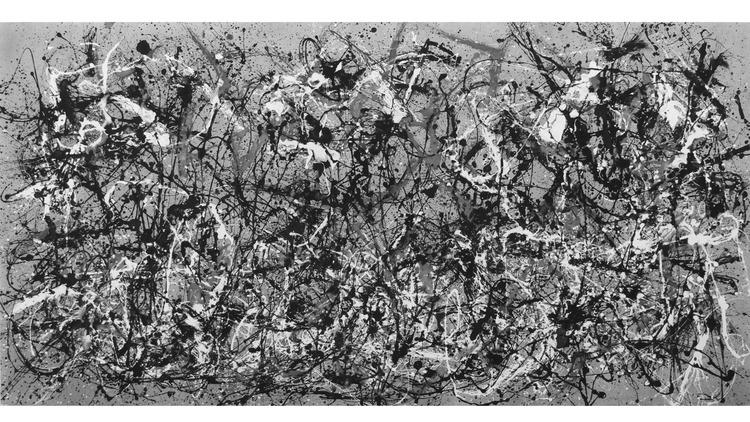

My drawing Capitol was in a show at the Aldrich museum in Connecticut, and I wanted to exhibit it here with Friedrich Petzel, who is my Berlin dealer. He suggested that I also present my new drawings of Abstract Expressionist paintings at Metro Pictures. The shows, I think, represent what we thought we could be versus what we are right now.

You’ve re-created some of the most famous paintings from Abstract Expressionism as drawings, using a level of detail that certainly seems exacting. How did you manage it?

Each painting required its own strategy for creating it. It was like waging war on several different fronts.

How so?

There was a lot of reading involved, conversations with various curators and art historians, and museum visits. Word got out as to what I was doing among the art handlers at different institutions, so as I went from the Whitney to the Guggenheim, more and more paintings were being pulled out of storage. I was like a kid in a candy store.

Did you take photographs of the work?

Yeah. We had to obtain permission from the estate of each artist to do that, but once we did, we had hi-res photos we could grid out to create a map of the canvas and the brushstrokes.

Why translate these images into black and white?

Because it makes everything seem that much more abstract. Also, as a kid, I didn’t read, I just looked at picture magazines like Life. And that's how I first saw the work of the AbEx guys, as black and white images in a magazine.

Why use charcoal as your medium?

I like the fragility of it. It’s just dust, and carbon is one of the primary elements of life. I also love the fact that charcoal can imitate the graininess of photography, as well as the velvety nature of painting.

How did you pick which paintings to draw?

It was highly subjective. Basically, I went with artists I really like, and chose paintings with an iconic quality.

Can you give an example of where your subjectivity came into play?

The Clyfford Still I used was at the Albright-Knox in Buffalo when I was a student there. So, that museum was an incredibly important place for me; plus, the scale of the painting is enveloping.

How important is that sort of scale to you, both in general and in terms of the way you approached the work of Still and the others?

Well, I’m an American, so big is good! And aside from cinema and big cars, those guys got to me. There’s a commitment involved to making something big and a commitment to owning it. But with these pictures, I actually changed the scale based on the size of paper of I was using. My Pollock, for example, is smaller than the original, while my Rothko is bigger

What prevents these works from simply being copies?

Again, it’s the subjective aspect of the translation process. The most important thing for me is that they’re not art about art, but art from art.

You mentioned seeing these paintings up close and personal. What was it like encountering them in that way?

It was like a mix of archeology and forensics. Viewing these works in real life made it possible to figure out how they were made.

Just how closely did you replicate them?

I didn’t want them to be photorealistic, but I did use some trompe l’oeil techniques to make the brushstrokes seem more alive. I wanted to locate the works somewhere in this weird zone between photography and drawing, where they could become themselves.

And also somewhere between abstraction and representation?

Well, I’m making representational images out of abstract paintings, so yeah.

Did any of the artists have a particular emotional appeal to you?

Pollock was an interesting case because I thought his work represented an artist who was fucked up and drunk. But I found out that his best paintings—the drip paintings—were made during a three-year period when he was sober. That struck a chord with me as someone who’s been sober for about 20 years now.

Getting back to the pairing of the shows, are you drawing a line between global power and art-historical preeminence?

There’s a little of that. While doing the research, I discovered things that I didn’t know, like the fact that the CIA had sponsored an exhibition of Abstract Expressionism that toured Europe. They were using the work to symbolize American might, and it’s role as the hope of mankind.

One of the pieces at Petzel is a sculpture in the form of an American flag sinking like a ship. Where did that come from?

When Congress is in session, they fly the flag over the U.S. Captiol, so the sculpture relates to my drawing, Capitol.

You’ve also titled it Pequod, after Ahab’s ship in Moby Dick. What is the relevance of the book for that piece?

Well, not just for that piece. The original movie with Gregory Peck was part of my life growing up. So was JFK’s death, which I also refer to in a drawing of a horse with an empty saddle, the one that led Kennedy’s funeral procession. So it’s like the flag is the Pequod and the Capitol is the whale; the saddle is Queequeg’s coffin. The Abstract Expressionists become the crew. Harold Rosenberg once said that the Action painters were like Ishmael going on a journey. But the icing on the cake was when I discovered that Pollock owned a dog he named Ahab.

Of course, the Pequod finally went down. Are you saying the same for the rest of us?

We have the same hubris that Ahab had. The idea that America has to be No. 1, the best, is what’s destroying us.

What do you think this show says about you at this point in your life and career?

To be successful as an artist you have to be driven, have talent and have a good work ethic. But you also have to be lucky. I think as an artist, the hardest thing about getting older is remaining relevant. That’s the real challenge, and I think what I’m trying to do with this show is stay relevant.

“Strike the Sun” opens at Petzel Gallery and “Gang of Cosmos” opens at Metro Pictures, both on Apr 10.

Discover Time Out original video