[title]

This is the second article in Back to Broadway, Time Out’s new series of interviews with members of the Broadway community who will be returning to work this fall.

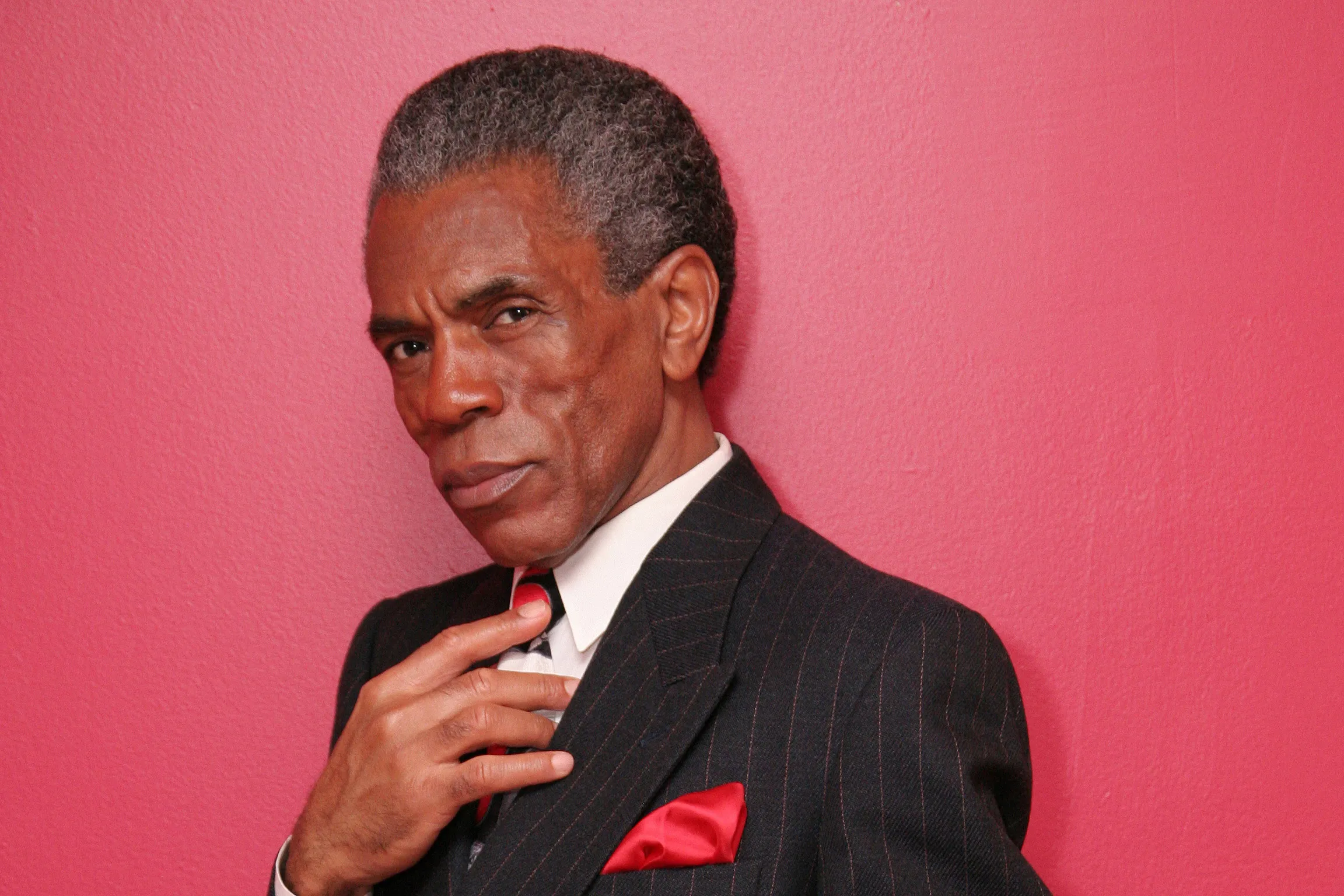

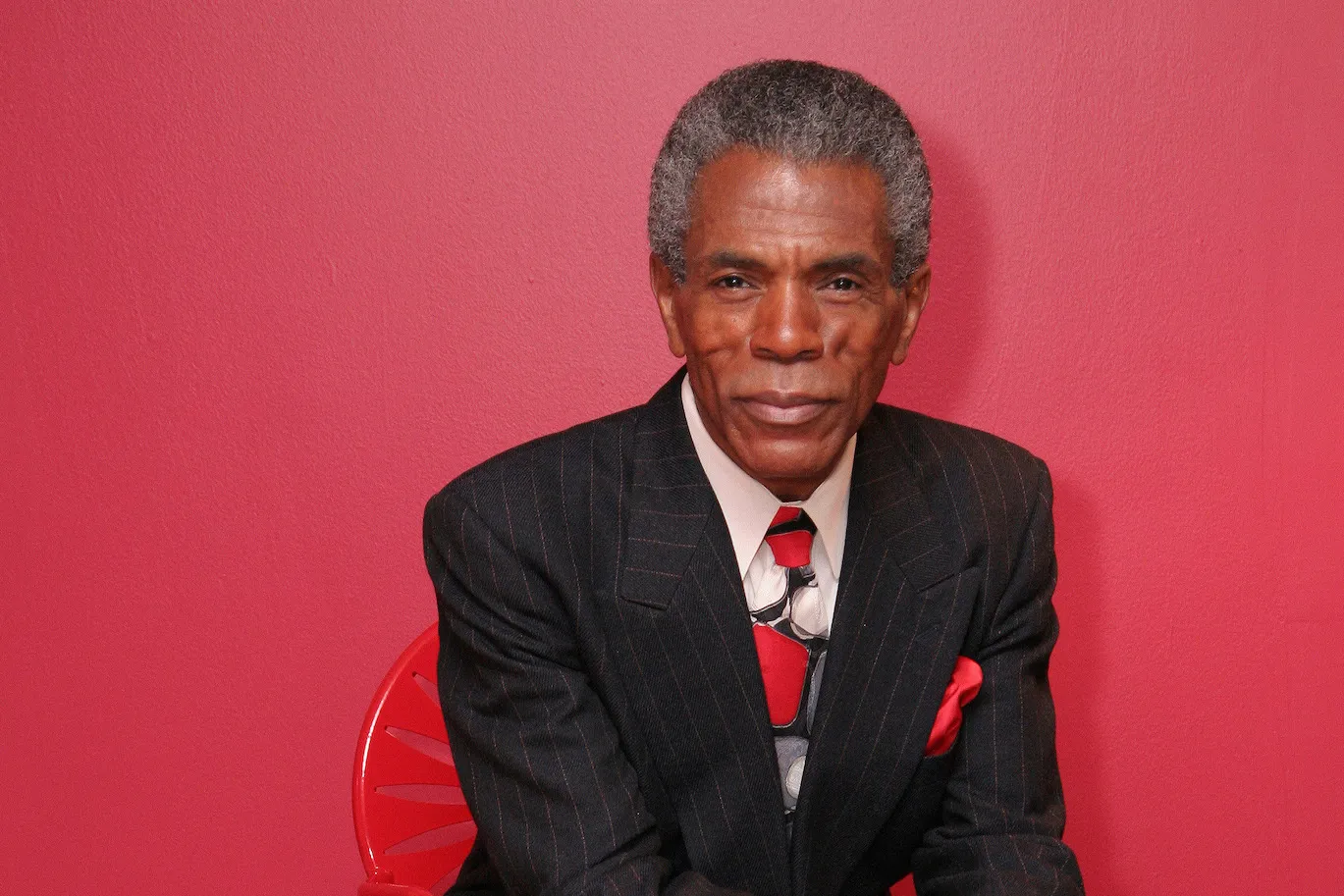

Not all actors are as fascinating in real life as they are onstage, but André De Shields somehow manages to be. That’s no small feat, because De Shields has been one of Broadway’s most magnetic performers for nearly half a century, bringing masterful command to the original productions of The Wiz (as the Wiz), Ain’t Misbehavin’, The Full Monty and now Hadestown, for which he won a 2019 Tony Award. He has also acted in many nonmusical roles, and has served as a director and choreographer (including for Bette Midler in the 1970s). In conversation, De Shields chooses his words with impeccable care, threading them with classical references and taking whatever time he needs—he is comfortable with silence—to express his expansive ideas about the universe and humankind. We talked with him by phone about his experience of the past year, his creative activism, his upcoming return to Hadestown and the lessons of living through a crisis.

You’ve been rehearsing for Hadestown for a week. Does it seem different to you in any way?

Well, of course it's different because it's coming deep into this era of the pandemic. It is in some ways celebratory because we have been separated from our Hadestown family for these past 18 months. On the other hand, a lot of it is commiseration because we cannot think that the only positive result of having spent these 18 months apart is that Broadway is experiencing a rebirth. We have to also understand that the paradigm is changing. For instance, while we are restoring the cultural spine to New York there's an instantaneous diaspora happening in Afghanistan. And although that may be categorized as geopolitics it is part of the collective that got destroyed when this pandemic hit us. One of the lessons we learn as artists is that a house divided can not stand. That's what the world is right now, that's what the United States is right now, that's what our communities in New York are right now: We are a house divided, until we understand that if we don't have this revolution we're all hungry for in a structure of discipline, it's not going to last.

What kind of revolution do you mean?

I'm talking about letting go of nostalgia for the norm, for the past—because the past has let go of us—and cultivating a nostalgia for the future. It takes an ostrich with its head buried in the sand not to realize that there is an old world that's dying. If we're smart, we’ll allow it to die. And if we’re wise, we will assist in its dying. Why? Because simultaneously there's a new world that's bristling with energy and yearning to be born. The paradigm is changing and we have to apply our art, our energy, our time and the most powerful tool we have, our imagination, in being good midwives to the birthing of this new world. You have to coordinate. You have to communicate. You have to cooperate. You have to collaborate. This is one of the reasons that Shakespeare has been such a powerful element for hundreds of years: because he understood, as many of us do today, that when nature is in discord it is simply and intricately a reflection of our own psyche that is in discord. Theater makers of the world unite! We are needed more than ever right now. It is not just our cause to get Broadway back on its feet. We are needed to teach that the definition of freedom is not personal choice. The definition of freedom is responsibility. We are most free when we take on responsibility for someone other than ourselves.

I'm interested in your focus on the future because, of course, you've had such a successful past. But then again, when you achieved success in the 1970s you were Black and gay in a Broadway community that seems to have been less welcoming in some ways—

It was less welcoming than it is today, yes.

—and since then, you’ve also been open about your HIV status, for example. What was your experience in those positions? Because you’re someone who managed somehow to be very successful despite that adversity.

Yes, and that’s because of the adversity. Here is one specific example: 9/11. What we learned from that in simple terms was: If you see something, say something. I believe if you know something, share something. That's what I did when I delivered my Tony acceptance speech. I was sharing what I know, what I've learned, what I have tested repeatedly and found: that the universe will conspire if you surrender to the balance that it requires, which is generosity and gratitude. The universe provides the generosity. Humanity must provide the gratitude. We continue to believe in the anthropocentrism of mankind, that we are the greatest of all entities in the cosmos. And that's what has gotten us into this apocalyptic setting that has caused us to act in fear and react in panic. Instead of building bridges, we're building walls. That's exactly the opposite of what we should be learning from how the paradigm is changing, how the patriarchy is falling, how the great male authority representatives are finally revealing themselves to be clay. The natural universe is moving away from patriarchy and toward matriarchy—toward nourishment, toward collective progress. Which the politicians like to call socialism, but that only creates more divisions.

The theater community has been in a reckoning with itself on questions of equal treatment and opportunity. Do you see good things coming from the discussions that were had and are still being had?

I do think something positive can come from it, if we just learn the lesson that every difficulty, every complication, every problem, every crisis is disguising a blessing. I know that sounds like New Age madness, but the greatest people who have ever lived have given us endless examples of exactly that, from the myth of David and Goliath to New Seeds of Contemplation by the monk Thomas Merton and the Joseph Campbell revelation “follow your bliss.” It all says, in different words, the same thing. If you avoid a problem, it will appear as insurmountable on the horizon. But if you approach the problem, you will see that it is porous and you'll be able to step through those holes. And before you know it, you'll be on the other side of the problem. So I have retooled that Latin phrase carpe diem—seize the day—and substituted another Latin word to make it carpe donum, which is seize the gift. The pandemonium has done what we've been praying for for so long. How many times have we said, Oh, if only the playing field were leveled? Well, that's what the pandemic did: It leveled the playing field. So now what?

One of the things that I find so fascinating about your career is that you’ve been in some of the greatest successes of the past 50 years—huge hits that ran for years and won Tonys and the rest— but also in infamous productions like Prymate, which closed in less than a week, and Rachael Lily Rosenbloom (And Don’t You Ever Forget It), which I don’t think even made it to opening night.

Right, it closed during previews. It's the first show I've ever done where people would stand up and actively boo the performance. [Producer] Robert Stigwood wasn't going to throw good money after bad, so he said, “Well, we're not opening, folks.” But there are reasons that we arrive at certain crossroads in our lives. When you come to a crossroads, the Sphinx sits there. If you can answer the riddle, you are allowed to continue on your path to your destiny, and eventually, your destiny rises up and says, “Hey, where've you been, we’ve been waiting for you!” But if you cannot answer the riddle, the Sphinx will eat you. That's where we are right now as humanity. If you cannot solve this riddle, you’re going to be eaten by the Sphinx. So get your shit in gear and stop bringing each other down, stop fighting, stop spending our lives accumulating stuff, which you can't take with you. What you can do is create a legacy for those who are coming in our wake. And that's by being grateful for the gifts that were here before us and that will persist after we’re gone. I'm talking about simple things like air, water, wind, trees. We have no respect for the natural phenomenon any longer. So why is it going to have respect for us?

Speaking of respect, you have been showered with honors in the last two years: the Tony for Hadestown, Lifetime Achievement Awards from the Theatre World Awards, SAGE and the York Theatre Company, a Key to the City in Baltimore, even a State Senate proclamation of André De Shields Appreciation Day. How has it felt to be on the receiving end of this flood of adulation, especially in the middle of a disaster?

Well, it's been invigorating. I could look at the past 18 months as a disaster, but during that same time I was able to harvest 50 years of the seeds that I've sown, and the harvest has come in a shower of abundance, as you've just mentioned. So I had to look beyond the pandemic and say, “Thank you.” That's gratitude. “Thank you.” I could have acted in fear like everybody else, but we are not bears who fatten up and go into a dark cave and hibernate for months. That is not what we do. So in the face of the pandemic, I had to carpe donum, seize the opportunity. And by doing that, I was able to remain gainfully employed for the past 18 months. People say, “André, how do you do it?” And I say, the answer is one word: surrender.

André De Shields | Photograph: Lia Chang

On a personal level, what is your takeaway from this time? Is there anything positive it may have given you?

Certainly, it's given me an opportunity to learn once and for all that the time of the lone wolf is over. If you're not cooperating, if you're not collaborating, if you're not participating in a collective—that is, at least trying to do the greatest good for the greatest number of people—you are lost. You're trying to make happiness of a collection of things. And that is not what we are about. Here we are at one of the greatest intersections of our lives. It doesn't happen in every generation that history and evolution intersect; more often than not, history is ahead of evolution or evolution is ahead of history. But here we are, at this clash of the titans, and we are not learning the lesson of…okay, there's no other word for it, but agape. It's a Greek word and it’s one of the most powerful examples of the word love, but it's love that subordinates one's individual advancement to another individual’s. That will draw us closer and closer to what Aristotle called the golden mean, when things are balanced. But if all you believe in is greed and capitalism and this God-awful sense of my individual right over yours, then it only means destruction. It only means decay, complacency, apathy, and all kinds of systematic wrongs like racism, homophobia, misogyny, fascism, all the conditions created by that negative energy. That's all the universe is: energy—dynamic, explosive mind-blowing energy that expresses itself in constant change. And here we are investing our time in trying to make things inflexible, trying to keep things normal, trying to get back to a world that was obviously infested with inequities. And we still are so far away from healing that wound that is American society, or I like to call it the United Plantations of America—not plantations only in the sense of enslavement, but plantations in the sense of demeaning another person’s humanity in order to create your material stock in life.

How does working as a performer intersect, for you, with the ideas you've been articulating?

We in the West, if you will, claim a legacy from Greece. Now, the ancient Greeks built amphitheaters to accommodate their nation states. Why did they build such large arenas? Because they believed that the gods who lived on Mount Olympus would come down and walk among them and answer their questions, solve their problems, resolve their crises, lift their burdens, break their yokes. And then of course, eventually we got to the top of Mount Olympus and discovered there are no gods there. And eventually we got to the moon and discovered there are no gods there. So what is it that we artists do? We're the only gods we have left. And it is our responsibility to walk among the nation states and answer their questions, solve their problems, resolve their crises, lift their burdens and break their yokes. That's why I am a performing activist: because I want to contribute to the healing of humanity's amnesia, humanity's self-loathing, humanity's hate for one another. We spend our imagination on things like hate and intolerance, and that's why it exists so strongly and so seemingly unalterably. But we can do away with it just as easily as we create it.

How long has this philosophical inclination been part of your relationship to performing? Were you thinking in these terms when you were making your way in the 1970s?

It's curious that you mention the 1970s, because I'm one of the few black hippies you'll ever meet. I'm an unreconstructed hippie. Not only do I believe but I know that love is the most powerful force in the universe—not lust, not affection, not desire, not quid pro quo relationships, but agape love. I will put your needs before mine and you will put my needs before yours and thereby establish a balance.

Am I mistaken that you got your start in the musical Hair?

In the Chicago production, yes. [Hair director] Tom O'Horgan came during my final month at the University of Wisconsin and held auditions and I won a role in the play. And the very month I graduated, I started my professional career.

Were you in Hair because you were a hippie or did Hair help form your hippie consciousness?

That was the universe conspiring. Obviously, Hair is about hippie love so that was bound to be my first professional show. But from my very first conscious thought, I knew that I would be an entertainer. Now, it wasn't until I was an adult and had adult conversations with my parents that I understood why I knew at a young age what my destiny would be. It’s because my mother's life's dream was to be a dancer, and my father's life's dream was to be a singer. But because of my grandparents, my father and mother had to defer their dreams because—I'll put it specifically in the words of my grandfather: "No decent colored child of mine is going to shuffle her way through life. We have barely shuffled our way off the plantation." Out of a family of 11 children, I'm lucky number nine in that those deferred dreams of my parents—when metamorphosed into X and Y chromosomes—had to be part of the conception of one of those 11 children. I'm the one. So I've never had to guess at what I wanted to do. I was going to manifest the dream, the deferred dreams of my parents. I was going to surrender to my destiny. And now I'm at another part of that equation, and that is to be of service to the enlightenment of humanity.

This interview series is about going back to Broadway, so I wonder what you're most looking forward to about restarting the show in a few weeks.

Again, I have to reference my Tony acceptance speech, and what I called my three cardinal rules of sustainability and longevity. Rule Number One was to surround yourself with people whose eyes light up when they see you coming. That's exactly what I’ve experienced with the family of Hadestown. Rule Number Two was: Slowly is the fastest way to get to where you want to be. And I'm continuing to practice that; my goal is to break the Methuselah code. And the specific response to your question about returning to Broadway is the third cardinal rule, which was: The top of one mountain is the bottom of the next, so keep climbing. I did not reach the pinnacle of the Hadestown mountain because the pandemic shut everything down. We were two months from achieving the pinnacle because we had all signed a run-of-the-show contract, which means you have to work 52 weeks. We didn't get to the 52 weeks. So returning to Hadestown is going to allow me to get to the top of that mountain and then do what I advise other people to do: Take a moment, appreciate the vista, and then look up and see the next mountain that you have to ascend.

Thank you for making time to talk tonight. I know we've gone a little longer than we’d planned.

Let me tell you something else that I’ve learned: Time is longer than anything. So we've gone 45 minutes instead of a half hour. That doesn't mean anything. You can never exhaust time when you are using it correctly. People say life is short. Life is not short! Life is long. It's how you live it that abbreviates it.

Hadestown resumes performances on September 2, 2021. You can buy tickets here. This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

RECOMMENDED: Back to Broadway: A Q&A with Moulin Rouge star Danny Burstein

André De Shields | Photograph: Lia Chang