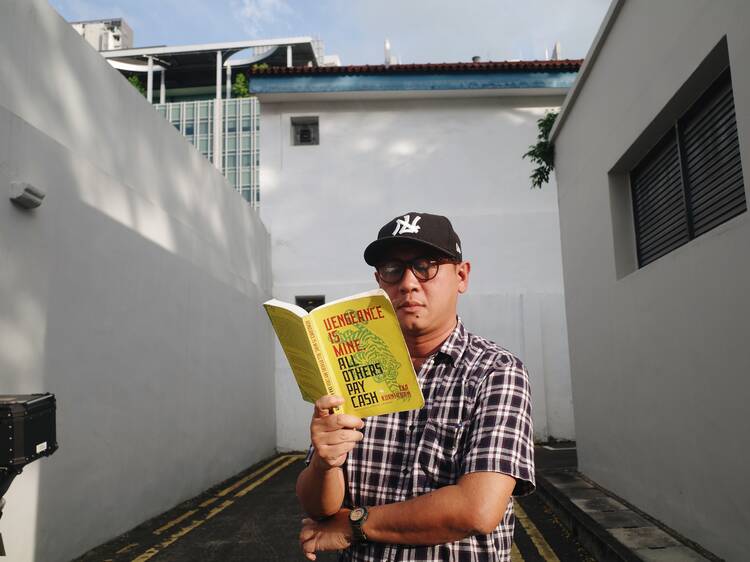

Singapore International Film Festival (SGIFF) returns from November 25 to December 5 in a full physical format. This year's edition presents a diverse, inclusive range of over 100 films filmmakers from all over the world and kicked off with Vengeance is Mine, All Others Pay Cash by Indonesian filmmaker Edwin. The feature became the first Indonesian production to win the top prize, or Golden Leopard, at the Locarno International Festival during its 74-year run.

The film, which is an adaptation of Eka Kurniawan's 2014 novel of the same name, is an 80's action drama that uses sexual impotence as a social critique. We chat with Edwin about the film, the topic of toxic masculinity in Indonesia, and working with Eka Kurniawan.

Hi Edwin! Congrats on the film premiere. How is it like to be in Singapore?

It feels like home. Not like in Jakarta, but in a more quiet, safe and calm way.

How do you feel about Vengeance is Mine, All Others Pay Cash being selected as this year's opening film for SGIFF?

I’m very happy and proud, especially because this is a co-production with a Singaporean company. I worked with five co-producers from Singapore. It feels like this is not only an Indonesian film but also represents Indonesia and Singapore. The film editor and sound designer are from Thailand, so this feels like our story. To present the film here, it feels like home. You know, we first premiered the film in Locarno, Europe, and then we went to Toronto, Hamburg. But this is the first time that I came to a film festival in Asia. It’s very close to Indonesia, so it feels nice to see the reaction of the audience who are more related to the context of the film. It’s nice to watch the film with an audience who understand or feel close to the film.

When did you first read the novel by Eka Kurniawan?

It was the first time they released the book in 2015. I was definitely attracted to the title in Bahasa Indonesia, Seperti Dendam Rindu Harus Dibayar Tuntas. I was definitely attracted to the title. It’s very poetic, very funny. There’s a lot of taste in that sentence itself. It reminds me of graffiti in the back of trucks. When you go to Indonesia and travel around, whether it is Jakarta or somewhere in Java, you will meet a lot of trucks on your journey. And those trucks always have graffiti – usually lewd stuff – at the back. The art or illustration might not be too beautiful, but you get that a lot of emotion and frustration – maybe even sexual frustration – goes into it. So the title itself reminds me of that feeling. The book was very fast-paced and very visual to me so I thought naturally that this could be translated into a film.

What were the challenges that you faced adapting the film into a novel?

I think the structure of the book is very complicated. And in terms of the structure, it’s very non-linear. And a lot of the characters have very interesting background stories. We had to really choose which characters to spotlight. In the book, of course, there’s the main character like Ajo Kawir. But there are other characters like Iteung and Budi who have their own stories that are really, really interesting. So that made it quite challenging because it's difficult to really choose which one you want to portray. And then there’s the location issue. It’s not that easy to find a place that had the right feel. In the end, we settled for a small and sleepy port town in East Java that felt nostalgic and not of this time.

How would you describe the relationship between the main two characters?

It's a love story basically, between those two characters, but they are just you know, they are not in the right place and right time. They have love for each other but they're surrounded by a rough and violent atmosphere. But essentially, this is a romantic film.

Your focus is on the topic of toxic masculinity, especially in Indonesia. Why do you think it's important to bring across the message?

I grew up with this culture of masculine culture during the 80s and 90s. During the military regime, Suharto was in power, the big 10 At the peak of their power. So toxic masculinity is really rooted in our culture, in everyday life. Although I didn’t come from a family with a military background, we lived in this kind of military discipline. I lived in a residential complex where 80 percent of my neighbours were in the navy – and it was normal to see violence everywhere.

Violence is something that is so normalised in Indonesia that you can say it's in our blood. We are used to repressed feelings and those feelings needed to be expressed. We didn’t have enough vocabulary to express, anger and violence is the only language we express – until now.

You addressed quite controversial topics. Did you have challenges with censorship?

I didn't really think about it until we finished the film. So I'm aware that self-censorship is going to be a challenge for all of us. Everywhere in the world, self-censorship is becoming a serious problem for art, writing and everything. So I am aware of that – and I don't want to be trapped. I'll just do my best. But then when we submitted the film, it didn't require cuts. I was quite surprised, but it's a good thing. So we can screen the film in Indonesia, the same cut that we have. Singapore everywhere in Locarno is the same film that we bring to everywhere in Indonesia.

How has international reception been?

They enjoy the action, the tribute to 80s cinema, a little bit of comedy, romance and horror.

The second part of the film seems to take a more or less magical surrealism approach that Eka Kurniawan is known for. Was it intentional to have that division?

Yeah, starting from after they were released from the prison, right? With the introduction of Jelita, a very strange and mysterious character. It was intentional – to ask the audience to have a different perception of the story and the context of violence.

Talking about Jelita, what does the character represent?

For me, she's a representation of everything that is unexplained. I think in Indonesia, there are a lot of questions or mysteries that are not easily explained. Whether it's a part of history that no one seems to remember, a controversial law, superstitions and myths – it's something we've lived with so comfortably that we don't question it. And sometimes, these things need to be reevaluated.

You and Eka Kurniawan's works follow a similar style but in different mediums. Is this your first time working together?

Right after I read the book, I continued directly to Beauty Is A Wound and Man Tiger. This guy is so amazing, it's crazy. I learned a lot from his work. I have a lot of questions about history and the identity of being Indonesian and he manages to piece it all together in his work perfectly. His works are deeply rooted in our history, culture and politics in very crazy ways and it really resonates with me. So I approached my friend who knew him and she connected us. When we first met, we talked about everything – music, film, books, pop culture.