June marks World Pride Month, when cities and communities around the world celebrate and advocate for LGBTQIA+ rights. Here's where you can fly the rainbow flag in Sydney right now.

In April 1987, the Grim Reaper ad first aired on Australian TV. I was 13 years and four months old and I’d only just experienced my first teenage sexual fumblings with a school friend in the garage out the back of our family home; after school, beside the pool table. I had no idea then what HIV/AIDS would or wouldn’t mean to me. I knew that two years earlier little Eve, one of the first children in Australia to be diagnosed with HIV, had been banned from her pre-school and in that same year, Rock Hudson had died. Three years before that, Australia had recorded its first AIDS-related death.

The Grim Reaper ad was designed to shock an entire nation into an education about the rising global health epidemic that had already reached our shores. In the ad, a grim reaper figure in a bowling alley plays a game of bowls, knocking out the lives of men, women and children indiscriminately. Some HIV/AIDS advocates insist that the ad did more to contribute to creating a stigma around the HIV virus and its associations with gay men, the effects of which are still being undone. At the time I wasn’t aware of the politics or the fallout or what symbolism was being read into what. All I knew was that I liked other boys just like Rock Hudson and after watching the ad at the age of 13 years and four months, I had the sinking feeling that I would end up like Rock Hudson too.

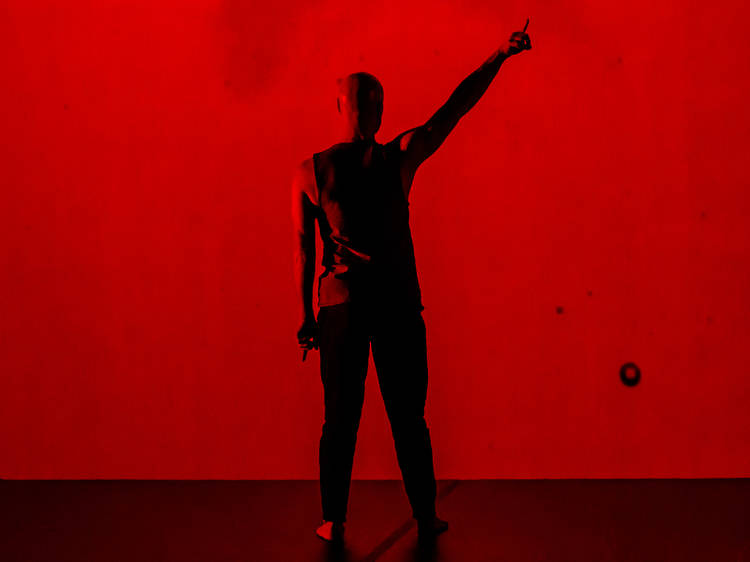

Photograph: Bryony Jackson

Photograph: Bryony Jackson

In 1996, I began dance studies at NAISDA, Australia’s longest-running and premier dance training institution for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander performers in Sydney. The years that followed set the foundations for a career in dance and an approach to creating theatre with songmen and songwomen from around our country and overseas. During my first year as a student dancer, I became friends with Anthony who studied dance at Redfern Dance Theatre, a rival Aboriginal dance school on the opposite side of the CBD. Anthony was an exquisite dancer. Limbs long and sinewy like a grasshopper and beautiful green eyes, too good to be on a man. We’d meet every Friday after class at The Shift Hotel, gay anthems blaring, disco lights going off like it was 3am. Within months of knowing Anthony, his boyfriend blurted out that Anthony was HIV positive and within a month of that, Anthony was found hanging from a ceiling fan in his bedroom.

In October 1998, a doctor in Erskineville had the job of giving me the news that would shift and shape and change my life forever. We sat in his painfully silent consulting room, the ticking of the clock above his desk sounding more like the beating of a tom drum. He took out a file and fumbled with his words. I eventually put him out of his misery and asked “It came back positive didn’t it?” He answered “I’ve never had to do this before. Yes.” He then began to cry. I consoled the doctor, he cleaned himself up and we scheduled my first appointment with St Vincent’s HIV Clinic on Oxford Street. I took myself next door to the pub and knocked back a vodka shot followed by a gin and tonic, with a beer.

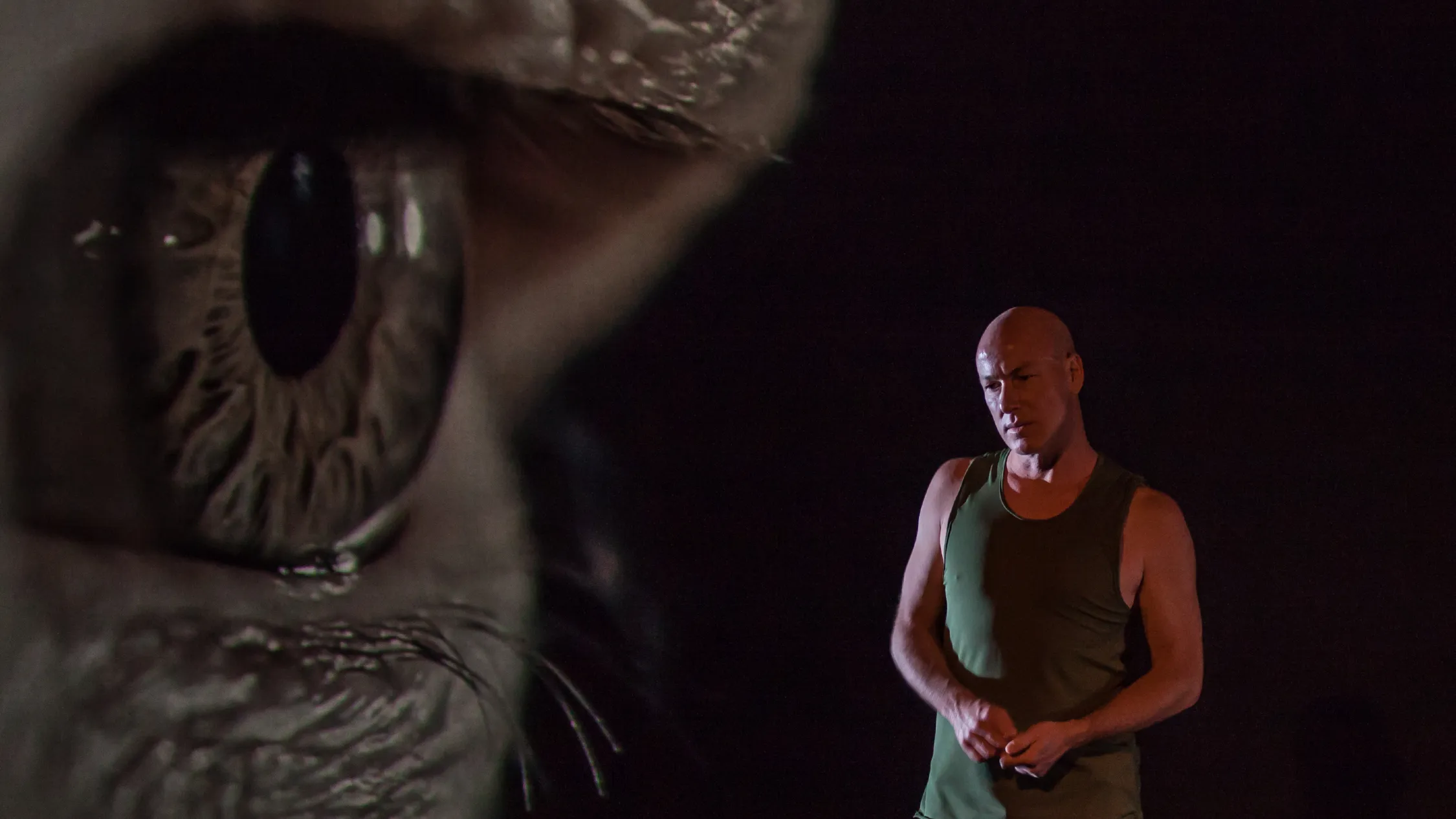

Photograph: Bryony Jackson

Photograph: Bryony Jackson

In 2013, the country was commemorating the first diagnosis of HIV. I was celebrating my own 15 year anniversary of living with HIV. And I was turning 40. As a birthday present (or challenge) to myself I decided to write a solo dance theatre work that I would also perform. I’d never performed solo before and thought before my tits hit my knees, I better get up on the stage for one last spin. The work would take the form of an autobiographical physical monologue and portray my experience of living with the virus and of the search to find love and to be loved.

It would most specifically speak to my experience of being a fair-skinned Blakfella and of HIV in Aboriginal communities. I’d never seen a stage play or a film, a tv show or even read a book about the Aboriginal experience of living with HIV. HIV is something our community doesn’t speak about. Yet, we are 1.6 times more likely to be diagnosed with HIV than our non-Indigenous neighbours.

And so, I wrote. I wrote for Anthony. I wrote to make up for the lack of targeted Aboriginal HIV programs and sexual health messaging for the past 30 years. I wrote for the absence of Aboriginal identified positions in HIV organisations that our mob could have turned to. I wrote to remember and honour all the mob that had lived with and died of AIDS-related illnesses and whose names would be forgotten and never spoken again. I wrote to give voice to our mob who live with HIV and to this day, stay silent because we are silent about HIV in Aboriginal communities across Australia. I wrote so that a part of our community could be seen and possibly invited into a conversation that’s been had without us for more than three decades. And I wrote to prove the point that we don’t all end up like Rock Husdon.

Blood on the Dance Floor premiered in 2016 and has since toured across Australia and Canada. It’s the first time I have been in a theatre space where our queer community and theatre junkies, dance lovers and First Nations audiences have gathered together to listen to the very particular voice and experience of an Aboriginal gay man with HIV.

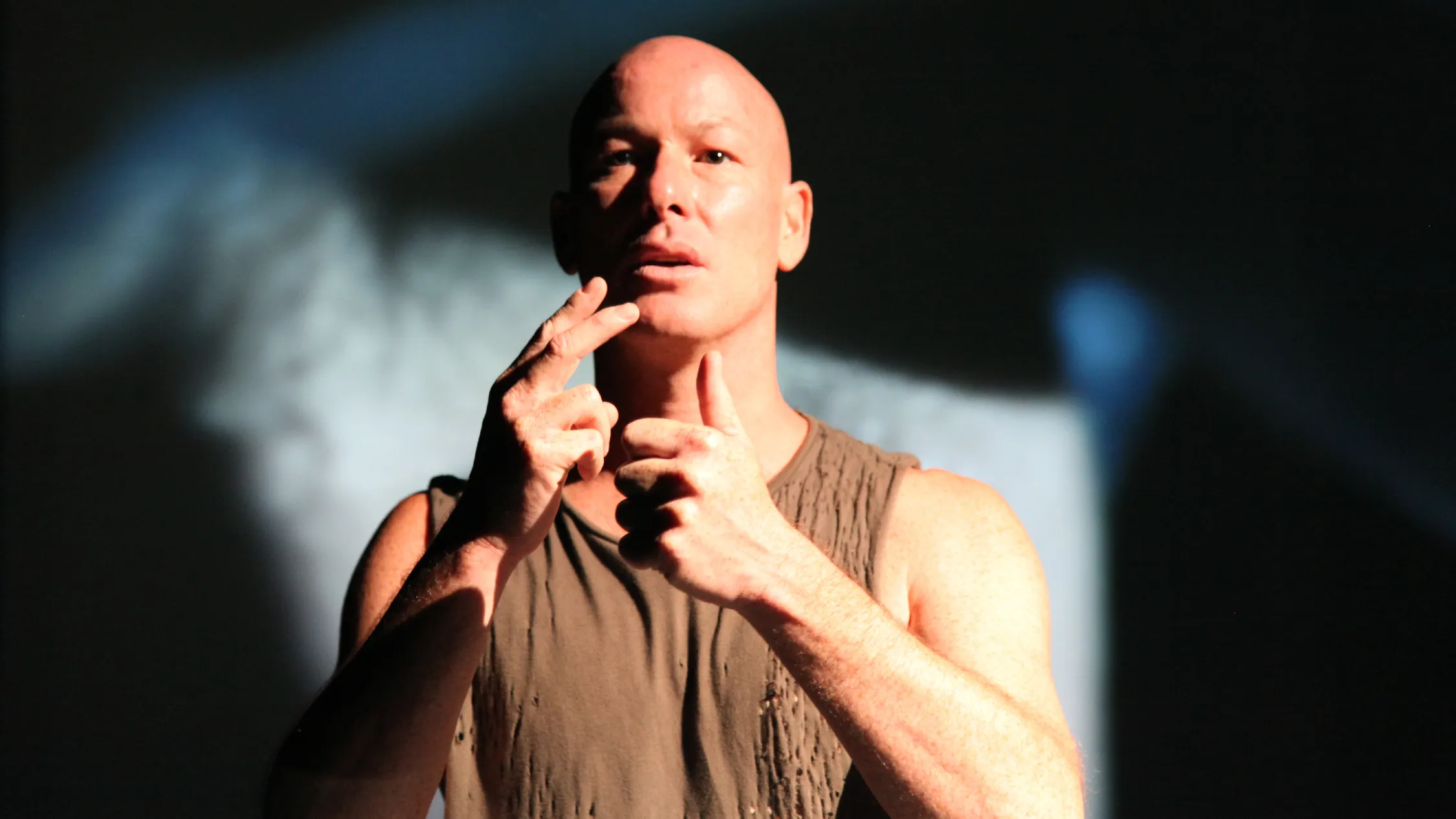

Photograph: Dorine Blaise

Photograph: Dorine Blaise

Since its premiere in 2016, cis Aboriginal women have been identified as being a high-risk group for contracting HIV, particularly those who are also IV drug users. When I toured Blood on the Dance Floor through Canada, I was shocked to learn that First Nations women on Turtle Island make up the largest number of people living with HIV, being 400 times more likely to have HIV than any other demographic in the country. Trailing behind cis women in our community back home are the cis Aboriginal heterosexual men who are climbing in numbers of HIV diagnosis.

Blood on the Dance Floor has lent itself to an ongoing body of work: a trilogy of personal stories about mob living with HIV. I’ve begun writing the second work as part of what I call The Blood Trilogy, this time focussing on cis Aboriginal women living with the virus. Representation in the public domain of a diversity of experiences living with the HIV virus is important. We look to heroes and role models for inspiration or guidance or just very simply, to see parts of our own selves.

I have been privileged with the task of documenting the life of a local unsung hero whose story is an important entry in the records of people who have lived, survived and thrived with this virus. It is both a privilege and critical, given the current rates of diagnosis, to be writing about a triumphant battle and the cultural complexities of being an Aboriginal woman and of living with the HIV virus. Not knowing right now when we might be able to gather in theatres safely again, the work will most likely premiere in 2022. And we can’t wait to share this story with you when we can.

Jacob Boehme is a multi-disciplinary artist, writer and director of the Narangga and Kaurna

Nations creating work for stage, screen and large-scale public events. An Australia Council

for the Arts Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Fellow, Jacob is currently the Artistic

Director of The Wild Dog Project, connecting songlines between South Australia, Northern

Territory and Queensland.