The truth is absolute. Right? Well, that could be a matter of opinion. Or not. But maybe?

This confounding tug-o-war between the crisp dimensions of objective fact and the fuzzier boundaries of subjective ‘truth’ is at the heart of this thoroughly meta Sydney Theatre Company production. Through the lens of a true(ish) story about a lot of lies, it explores the tension between the fictions we choose to believe and the realities that stand up to confront them.

Two of the trio of roles in this three-hander are based on real people: celebrated essayist John D’Agata and one-time journalism intern Jim Fingal. In 2003, Harper’s Bazaar commissioned D’Agata to write an in-depth essay about the suicide of a teenager in Las Vegas. However, when plucky intern Fingal was assigned to fact check the piece – considered an easy bit of busy work for a budding sub-editor – he discovered hundreds of discrepancies – some small and forgivable, others egregiously fast and loose. But this wasn’t a mere case of carelessness on D’Agata’s part. In telling the story of how a young man came to leap to his death from the observation tower of a Sin City casino, his essay sought to force beauty’s will onto the beats of this teen’s last day. Simply substituting the elegantly crafted inaccuracies with their blunt factual counterparts would gut the essence and atmosphere of D’Agata’s writing, or so he insisted. Which raised a curious question: what’s more important – honesty, or artistry?

It took Fingal and D’Agata almost a decade to hash out an answer to this, with the 2013 publication of the co-authored book from which this play was adapted by Jeremy Kareken, David Murrell and Gordon Farrell in 2018. And given its content – plus the unanticipated resonances today’s disinformation culture brings to this production – it seems not just forgivable but entirely apt that the stage retelling of these events should also distort the truth.

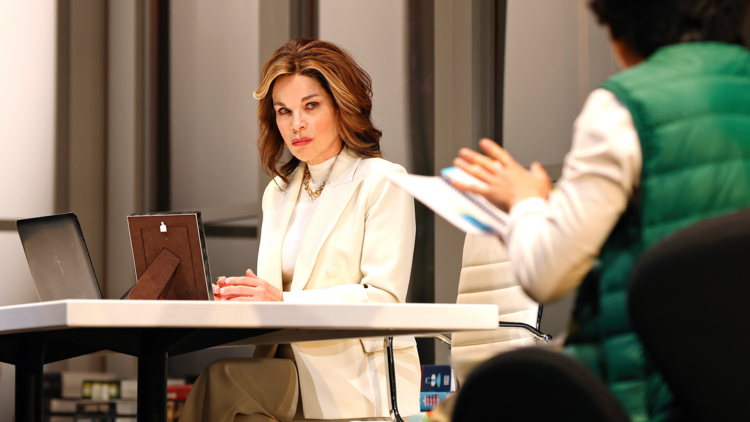

The broadest strokes of the narrative are faithful to their inspiration, but the fine details care little for the facts. Most notably, a fictionalised composite character, magazine editor Emily Penrose (Sigrid Thornton in her STC debut), is added to provide context – both of the practical constraints of seeking truth under the tyranny of a deadline, as well as the slipping value of integrity in an industry that is slowly atrophying. As the play unfolds it gradually shapeshifts from a piece theatre vérité into a more philosophical sparring match, with Penrose playing referee as D’Agata argues the virtues of poetry against Fingal’s factual pedantry.

There are also clear liberties taken with the characterisations of these two men, to allow them to more easily shift the action from that of a biopic into a more intellectual realm over the course of this one-and-a-quarter-hour show. D’Agata (Gareth Davies) is a puffed-up diva, resistant to the mere suggestion that facts should overrule the rhythm of his words. Fingal (Charles Wu) channels a similar hyperbole, going to extraordinary, near-superhuman lengths to research in microscopic detail each and every line of enquiry, arguing for the most unimpeachable standards of integrity, above and beyond the call of any intern’s duty.

Now established as an immovable object meeting an unstoppable force, D’Agata and Fingal seamlessly transform into totems of their respective beliefs, in a way that sweeps aside social decorum or the innate power imbalance of a lowly intern going toe to toe with a venerated writer. On this idealised battleground where influence, status and being ‘somebody’ no longer matters, the strength of the arguments alone can cross swords. Delivering meta on meta on meta, the play itself becomes an essay on the way humanity, with all its flaws, its yearnings, its need for pathos and redemption, is an imperfect prism for the cruel sterility of fact. Especially when it gets in the way of a good story.

But I hasten to add that while this is a deeply thoughtful play, with a lot of intellectual red meat for those who are hungry for it, it’s also a helluva lot of fun. There’s a wonderful odd couple dynamic between Wu’s dorkiness and Davies’ world-weary exasperation. Thornton finds a goldilocks shade of Madison Avenue swagger (not too Miranda Priestly, not too Carrie Bradshaw, but just right) to fully round out the emotional terrain, and the chemistry between all three of these actors is a riot, philosophical musings notwithstanding.

Indeed, director Paige Rattray’s vision for this production is a similar melding of whimsical charm and quiet brilliance. There’s a lot of surprisingly physical comedy at work as D’Agata and Fingal butt heads, and amping up these moments of comedic relief helps to blunt the sharper edges of a show which spends quite a bit of time discussing suicide in not always the most delicate way.

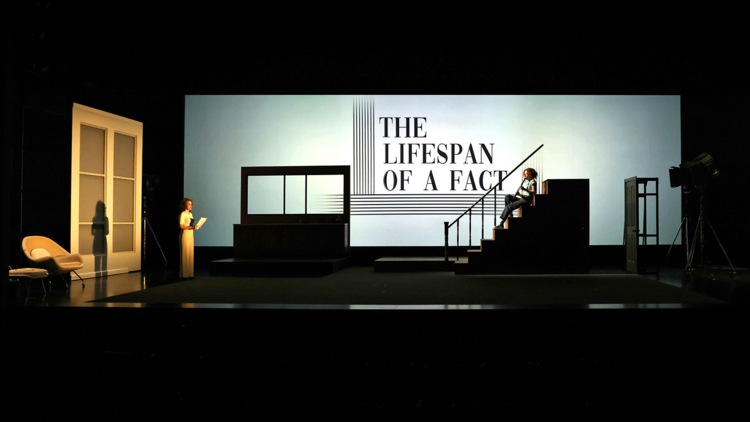

But Rattray also finds scope for some intellectual flexing of her own. Summoning the spectre of Bertolt Brecht (the German theatrical innovator who prized bulldozing the fourth wall in order to make the stage’s artifice a conspicuous conceit), the use of projected titles, on-stage costume changes and the absence of wings, all frames the action as a fabrication from the outset. A wandering on-stage clarinettist, who plays phone ringtones and bluesy incidental ditties, is another Brechtian wink that keeps the audience away from any suggestion of realism (although whether this flourish adds much to the production is a little dubious). Marg Horwell’s set of trundled pieces and half-built structures against a sprawling vista of the Nevada desert also follows suit, while containing the action in a more intimate space – a useful trick, given the potentially overwhelming size of the Roslyn Packer stage for such a small-scale play.

You could be forgiven for thinking The Lifespan of a Fact is some kind of morality tale, but there’s no finger wagging to be seen in this production. Here in the real world back in 2003, Harper’s Bazaar eventually opted not to publish D’Agata’s essay because of its shortcomings (it would be ten years before another magazine would take a punt on it). However, in the make-believe world of the play, the essay’s fate is left as a question mark. This isn’t a cliffhanger per se, but more a bit of homework, as the audience is left to ponder what they might do themselves in Emily Penrose’s shoes.