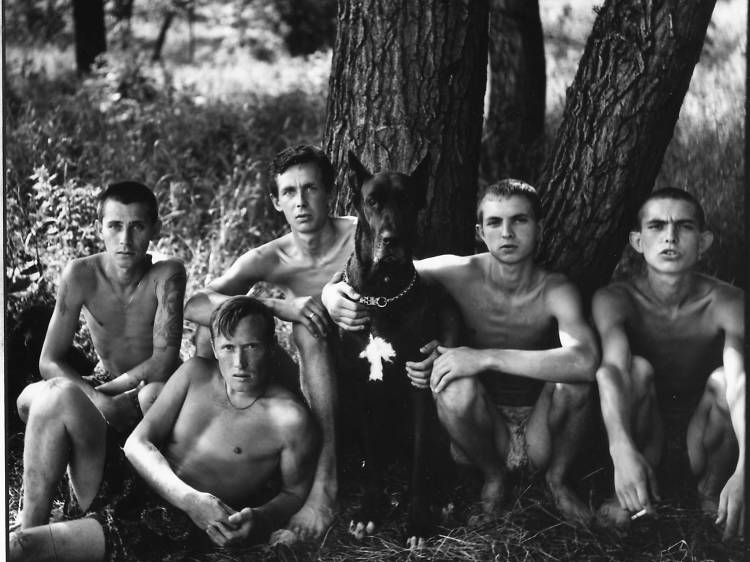

Nikolai Bakharev

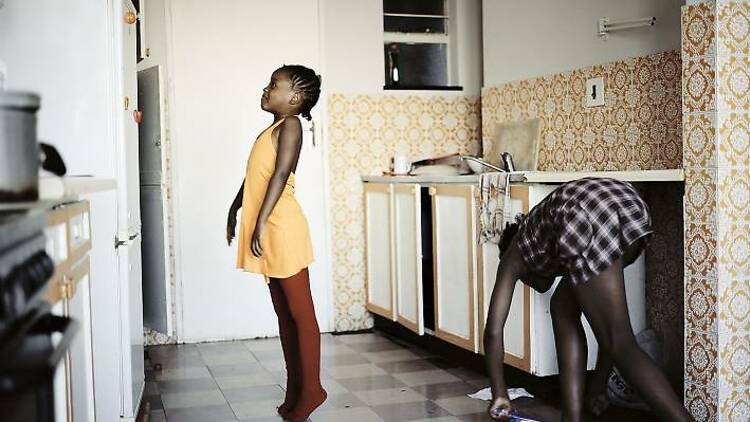

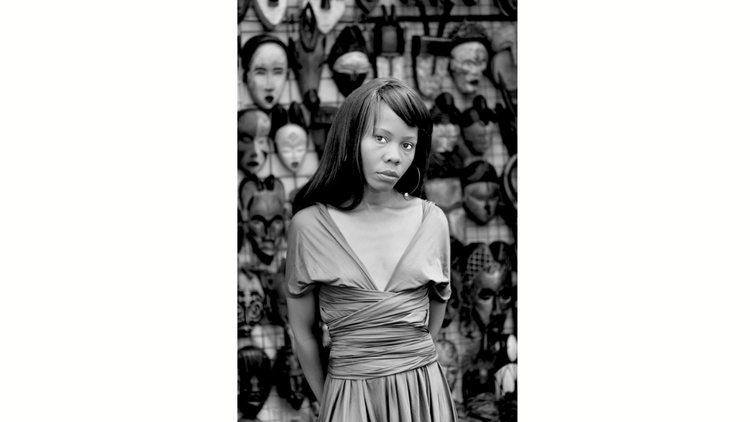

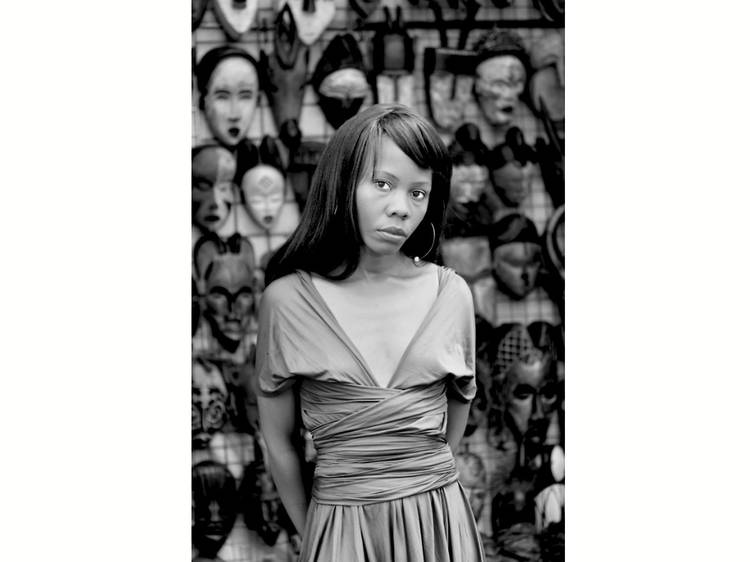

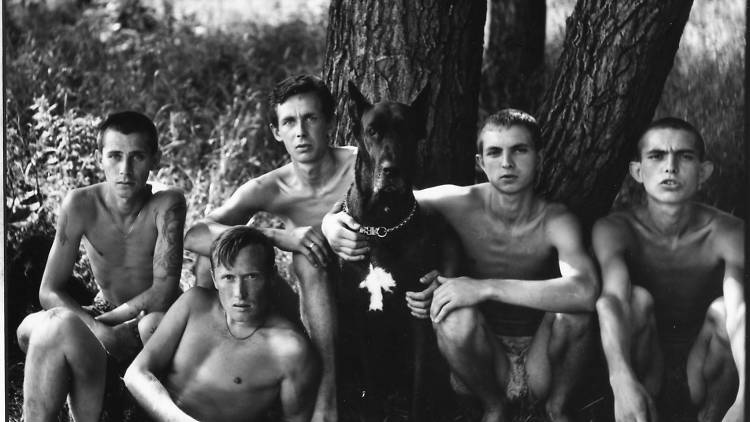

A photographer for the ominous-sounding Communal Services Factory during the Soviet era, Russian artist Nikolai Bakharev found himself snapping weddings and kids’ parties to supplement his income. This is how he came to shoot this series of bathers on Russian beaches during the 1980s. His subjects are just couples and families on days out (in fact, the photos on show are the ones his sitters didn’t want to keep). Except, of course, they’re way more than that. Curiously difficult to date, these black-and-white photos of unnamed subjects exist in a beguiling hinterland between the private and public, the informal and staged. It’s the most coherent display, and the easiest to digest, but by concentrating on one aspect of his work it gives little indication of Bakharev’s breadth. A couple of interior shots of women slouching and smoking suggest that as a photographer Bakharev packs way more than just swimwear.