[category]

[title]

Review

The Anmatyerr artist Emily Kam Kngwarray only took up painting during the last decade of her life. Making up for lost time, she produced thousands of paintings in the years leading up to her death in 1996. She worked frenetically, changing her style multiple times. This, her first major European solo exhibition, presents just a sliver of her oeuvre. It’s an impressive introduction to a visionary artist and, to those unfamiliar with Aboriginal art, a new way of understanding art.

Naturally, this show needs more exposition than most. It requires European audiences to let go of their art-historical baggage. For example, the colourful works on show here aren’t straightforwardly representational but it would be wrong to call them abstract. Rather than leave us to experience Kngwarray’s work on the familiar-but-inaccurate terms that define western art, the exhibition takes two rooms to provide a potted education on Aboriginal art and life and the artist’s place within it. Dreaming, for example, is an important religio-cultural term that pervades the exhibition, connecting Aboriginal Peoples with their ancestors through the land.

This show needs more exposition than most

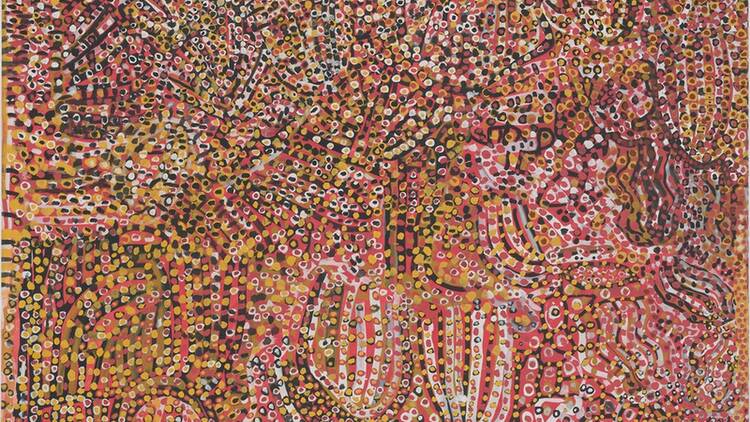

The exhibition finds confident form in its third room, where more than a dozen large-scale acrylic paintings, all replete with coloured dots, surround a procession of batik prints on silk that hang from the ceiling. Interconnectedness is less a feature of these works than an underpinning of them. In each of the paintings, the matrix of spots obscures and interacts with a web of pathways, arrows and nodes.

Ntang Dreaming (1989) is a resplendent example which I’m told depicts the seeds of the woollybutt grass that surrounded Kngwarray in her ancestral country of Alhalker. In the batik works, made using a labour-intensive process that the artist eventually gave up to start painting, such subjects find a more ethereal outlet. Untethered from canvas and wall, with light filtering through them, the images of flora and fauna become airborne constellations.

Unimaginatively, works like these have often been compared to the also-spotted paintings of the Pointilists. Though I wonder how useful pointing out western counterparts is, I think Kngwarray’s work has more in common with that of more contemporary American painters like Terry Winters and Forrest Bess, who look for profundity in patterns and symbols.

There is no shortage of work by Kngwarray to show here, and the exhibition does a good job of cycling through various groupings without feeling too brief. A film made during a 2023 research visit to the artist’s home in the Sandover region of northern Australia gives texture to our understanding of her life and work. It also shows us where the intense and earthy reddish-brown colour (used in many of the paintings) came from: unsurprisingly, the earth.

Some of the exhibition’s best and most dramatic paintings come toward the end. In the eighth room, a monumental 22-panel painting is joined by multiple other works more colourful and explosive than anything that we’ve seen so far. Here, Kngwarray’s dots are more frenzied than before, forming bulbous lines that traverse sprawling canvases. They look more like they were painted with massage guns than brushes.

It’s one thing to introduce a new artist to museum-goers; to present them with an alternative way of looking at art itself is a different ball game. Here, Tate Modern presents Kngwarray as a part of the Aboriginal art paradigm within which she was so important, enriching our experience of her work by refusing to sell it short.

Discover Time Out original video