To say that ‘Manet: Portraying Life’ at the Royal Academy is a straightforward exhibition of portraits by the great French painter Édouard Manet would be like saying that Pablo Picasso painted straightforward portraits of his sitters. Unlike Picasso, however, Manet’s female subjects don’t have their noses purposefully put out of joint or their eyes misshapen or misaligned – indeed, they are often intensely beautiful and seemingly traditional in both poise and dress.

Take one of the gems in the show, ‘The Railway’ of 1873, coming from the National Gallery in Washington. It depicts a fashionable young lady and a girl in front of some iron railings. So far, so straightforward. Except the petite fille isn’t looking at us at all, but staring away at a puff of steam or smoke billowing out of an unseen train, disappearing somewhere beyond our view. Artists weren’t meant to paint ambiguities or withhold information in this way and portraitists were sure as damn meant to actually paint faces, but Manet regularly confounded expectations of what a picture could be by denying such rigid conventions and showing people in comparatively realistic, unstaged situations.

This is one reason why Manet is often described as a thoroughly modern artist (perhaps even the first?), despite having been born in 1832, half a century before Picasso. He also died prematurely in 1883 (of the dreaded syphilis) but still bestrides his century as one of France’s most important and influential artists, just as the stocky, long-lived and similarly promiscuous Spaniard would monopolise much of the subsequent, twentieth century. However, Manet refused to wholeheartedly break from tradition or forsake his heroes from art history, as his impressionist colleagues and contemporaries would do in the last few decades of the nineteenth century, when they began so rudely dashing their brushes against convention.

Still, Manet was something of a mentor figure for this generation – Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas and many others regularly met at the Café Guerbois near Manet’s Paris studio. Certainly his fast and loose style of applying paint to canvas and his ability to whip up a portrait in a solitary sitting influenced the speedy, outdoor plein air (direct-from-life) techniques of impressionism. But what separated him from, and even elevated him above his younger charges, can be seen in another fantastic work in the RA show, Manet’s portrait of ‘The Monet Family in Their Garden at Argenteuil’ (1874). Although it’s a sketchy, impressionistic work true to the spirit of his friend’s artistic vision, it’s also an incredibly witty, conceptual portrait of the Monet family, in which Claude, his wife Camille and little Jean are all mirrored by another family unit at the left of the picture, comprised of a cockerel, a hen and a fluffy baby chick.

Such distracting visual trickery, as well as Manet’s infuriating habit of not finishing or glazing his pictures – he often cut them into smaller pieces, too – wouldn’t have sat well with customers paying to have their portraits painted, but in truth there were few such posing punters. His portraits were so far from the standardised norm, having more in common with the informal, immediate photographic carte de visites becoming fashionable at the time, there probably was little or no market for his hybrid, though-provoking creations.

Neither did this flouting of artistic genres go down well with the buttoned-up newspaper critics (one of whom described a Manet portrait as ‘an indecent and barbarous smear’), nor with the guardians of the Parisian Salon, the arbiters of official taste, who rejected his submissions on four separate occasions. Manet didn’t much care (although he did once describe the critic’s attacks as like lashes of a whip). He painted largely for himself, his social circle and for the love and challenge of it.

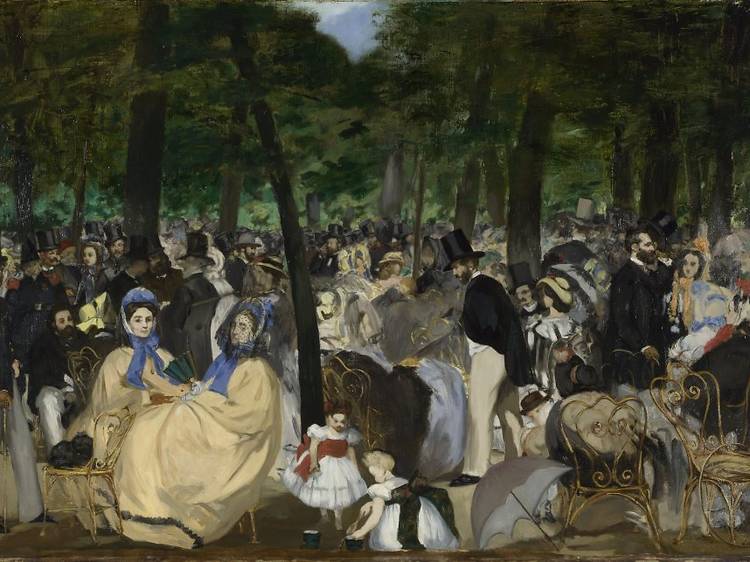

His father, Auguste Manet, was a senior civil servant in the Ministry of Justice and a property-owner of the upper middle class. Consequently, Édouard could do as he pleased without fear of running out of funds or having to flatter any dignitaries and so spent his days fraternising with left bank intellectuals such as Emile Zola, Stéphane Mallarmé and Charles Baudelaire. The latter of these literary giants not only features in Manet’s giant, teeming composition of a high-society concert in Paris (that also includes a self-portrait), ‘Music in the Tuileries Garden’ (1862), but Manet himself matched the portrayal of the passionate observer described in the poet’s famous 1863 essay, ‘The Painter of Modern Life’.

‘Today I want to discourse about a strange man,’ begins Baudelaire, ‘a man of so powerful and so decided an originality that it is sufficient unto itself and does not even seek approval’. This semi-fictional painter of modern life, Monsieur G, is both an idler and a keen spectator who manages to distil the eternal from the transitory. This notion of the dandified flâneur, who strolled aimlessly around Paris in order to collect morsels of everyday urban life – its characters, scenes and ideas – suited Manet’s artistic stance, which Honoré de Balzac also later summed up as a ‘gastronomy of the eye’.

None of which, frustratingly, gets us much closer to Manet the man, as it were. His mysteriousness – he rarely wrote letters and was by all accounts a loving husband and father, notwithstanding his occasional proclivity for prostitutes – means that we have to piece together his innermost thoughts and artistic drives through pictures alone. For instance, the 1876 portrait of Mallarmé, a difficult but brilliantly lyrical poet, is fittingly clouded in the haze of the poet’s cigar smoke, and has the writer staring off into space in a practically horizontal repose, as though lost in his own world. Elsewhere in ‘Portraying Life’, Manet thrust his models into acting out roles of street urchins or impoverished but noble singers. This was not straight portraiture.

Two of Manet’s most famous pseudo-portraits featuring strong, but vulnerable women are not coming to the Royal Academy’s exhibition. ‘Olympia’ (1863), the forthright nude, reckoned to be the depiction of a high-class call girl, is forever imprisoned at the Musée d’Orsay, as one of its biggest attractions, while the equally arresting ‘A Bar at the Folies-Bergère’ (1882) remains one of the stars of the Courtauld Institute at Somerset House (and was voted our number one painting to see in London, see timeout.com/unmissable20). Are we any worse off for not having the full complement of Manet masterpieces in this show? What exactly is the full picture, when it comes to a painter who erased or hacked off whole portions of his work, often leaving them with these gaping holes?

Perhaps one of his few surviving letters can shed some light. In 1880 Manet wrote to Antonin Proust about his recently painted portrait of the politician and journalist: ‘My dear friend, you cannot believe how discomforting it is to plant a figure alone in a canvas and to invest in it all one’s interest, without losing its life and presence… I trust that later they don’t stick this portrait in a public collection! I’ve always had a horror of that mania for piling up art works without letting the light of day between the frames, just as one puts the latest novelties on the shelves of fashionable stores. I leave it to the hands of destiny.’ Clearly Manet saw each portrait, not as an image of someone’s social stature or outward trappings, but as a personal and wholly individual homage to the character and inner life of that person. Only by standing among them will they come alive once more.

26 January 2013 to 14 April 2013

Key. 31 / Cat. 26

Edouard Manet

Music in the Tuileries Gardens, 1862

Oil on canvas

76.2 x 118.1 cm

The National Gallery, London. Sir Hugh Lan

Discover Time Out original video