Did cavemen invent immersive art? When they painted bulls and stags on cave walls, and lit them with flickering firelight, were they presaging Yayoi Kusama and teamLab? Some scholars think so, believing that palaeolithic cave art is a direct ancestor of the modern, technological art wonders that have become so popular. Others think that immersive art is a contemporary con, a clever ruse designed to separate punters from their cash with the promise of the perfect selfie.

Con or caveman, it doesn’t really matter, because immersive art is absolutely everywhere, especially in London. We’ve got immersive Van Gogh and Klimt experiences, with classic art projected across the walls of Docklands warehouses; we’ve got immersive-specific art galleries like Superblue; we’ve got Kusama ‘Infinity Mirror’ rooms at Tate. We’re drowning in immersion.

The combination of technological wizardry, participatory high jinks, sensory overload and full-body experience has proved to be totally irresistible to London’s art-loving public. But it’s nothing new. Immersive art has been drawing the crowds in this city for decades.

There’s an argument to be made for theatre as the first truly immersive artistic experience in London – with new technology in the late nineteenth century leading to bigger, bolder, more intense production styles – but when it comes to art, things happened a little later. In 1965, Gustav Metzger created ‘Liquid Crystal Environment’ by placing heat-sensitive liquid into glass slides and rotating them in the heat of a projector, creating swirling, dizzying light environments. Viewers would stand surrounded by undulating multi-coloured forms, a psychedelic maelstrom for the whole body.

In 1966, Metzger’s work was used as the stage set for a gig by Cream and The Who at the Roundhouse, so it would have been seen by thousands of people. Just imagine if they’d had Instagram! ‘Liquid Crystal Environment’ had a huge impact and influence, and has a strong claim to being the first truly and intentionally immersive work of art, in London at least.

This was art built to constantly change and evolve, to never be the same twice, but also to totally overwhelm the viewer’s senses. When the work was recreated last year for the Barbican’s ‘Postwar British Art’ exhibition, it was one of the highlights. In an exhibition filled with paintings and sculptures, it felt shockingly modern, like something made last year, not last century. With ‘Liquid Crystal Environment’ Metzger, as in so much of his work, was way ahead of his time.

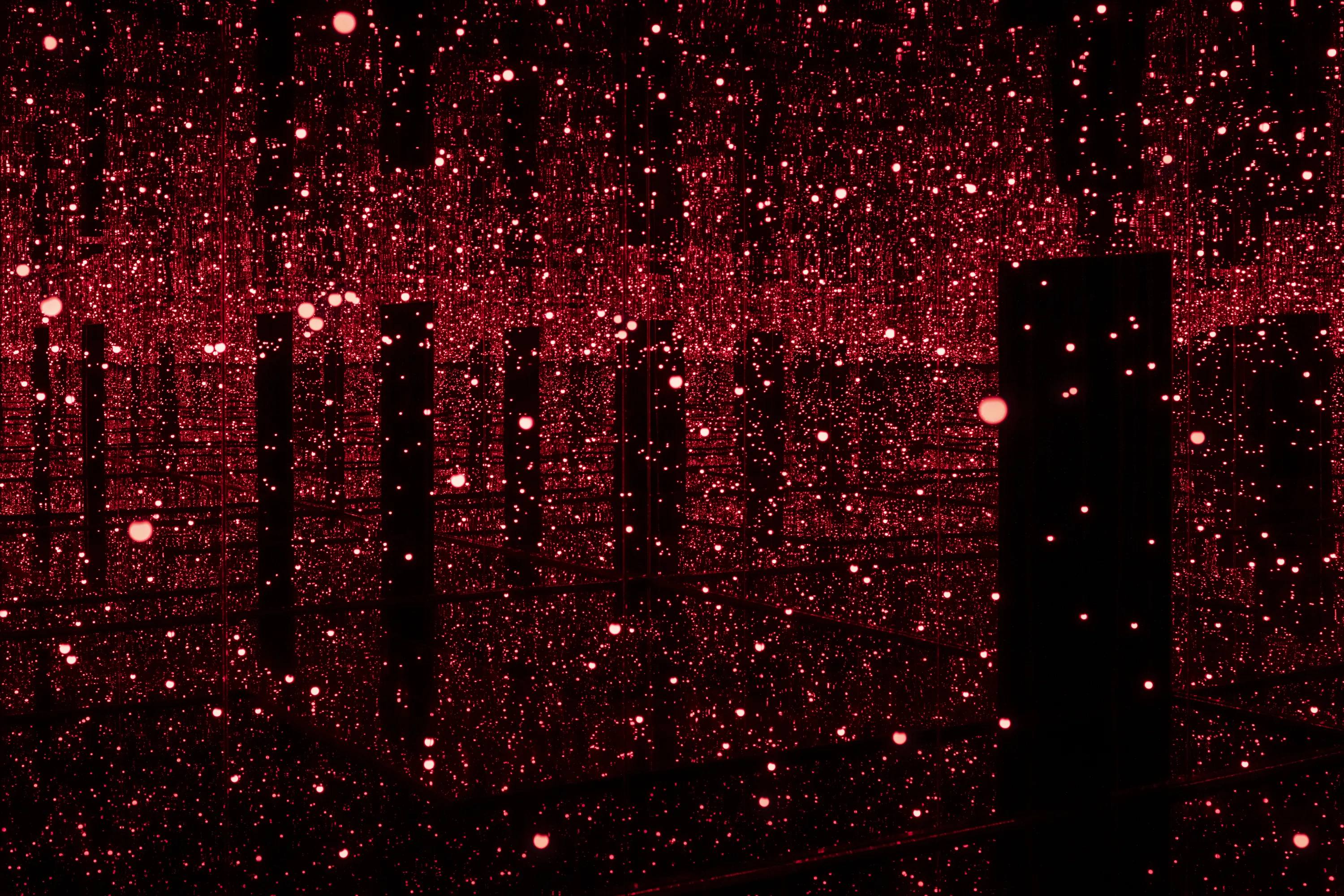

Also in 1965, over in New York, Yayoi Kusama was creating her first ‘Infinity Mirror Room’ at Castellane Gallery. It combined sculpture, light and mirrored walls to create a dizzying environment that has now become one of the hallmarks of immersive art, and one of the most famous artworks in the world today.

While other artists around the world at the time were dabbling with work that the viewer had to physically inhabit – like Bruce Nauman and his brutally oppressive corridor works – few others were going for full-on, full-body immersion like Kusama and Metzger.

Eventually in London in the 1980s, there were works like Rose Finn-McKey’s steam installation at the Chisenhale and Richard Wilson’s incredible walk-in room of crude oil at Matt’s Gallery, which were stunning sensory works of art, but not actually immersive in the way we think of it today. They were quite hard to take selfies in, essentially.

But then, in 2003, Olafur Eliasson filled the Tate Turbine Hall with weather, and everything changed. A huge gleaming sun hung from the ceiling, fog poured down the walls. For one whole winter, London had a permanent sun. People came and had picnics in the Turbine Hall, spent hours basking in the art’s glow. A proper, full body, immersive experience.

And it made something click in the UK art scene: artists and curators realised that viewers wanted, needed, more. Maybe it’s because we’d all got used to surroundsound at the cinema, or plays that made you a participant, but art now had to do more to compete, and at the same time, artists realised that they could harness the power of immersiveness. But even then, it was hard to anticipate quite how saturated with immersive art London would become.

In 2007, the Hayward Gallery put on a big, ambitious exhibition of work by English sculptor Antony Gormley. It was full of his human-sized steel sculptures, but one work captured the public imagination like no other. ‘Blind Light’ (also the name of the exhibition) was a box in the middle of the gallery, seemingly filled with an impenetrable wall of whiteness. But it was penetrable: you could enter and immediately lose yourself in a dense cloud of light, like being stuck in the thickest fog imaginable.

Ralph Rugoff is the director of the Hayward Gallery, and curated that show: ‘While “Blind Light” offered a disorienting immersive experience not dissimilar from earlier fog environments by artists like Ann Veronica Janssens, it was also designed so that spectators outside the box could watch bodies appearing and disappearing in the mist as people approached and then moved away from the glass walls. That twist – whereby the visitor’s immersive experience becomes a spectacle to be witnessed by others – seems kind of prescient looking back at it through the lens of our current social-media landscape.’

It was a viral sensation before viral sensations were even really a thing; there were pictures of it absolutely everywhere, and every other major institution took note: if you could get people to post pictures of themselves in your exhibition on social media, you’d be getting the best marketing money could pay for, and it wouldn’t cost you a penny.

It was a viral sensation before viral sensations were even really a thing

At a similar time, commissioning body Artangel unveiled Roger Hiorns’s ‘Seizure’. It was my first experience of a truly immersive art work – not just an installation or being stuck a couple of feet away from some terrifying nude performance artist – and it was genuinely mindblowing. An abandoned council flat in south London had been pumped full of liquid copper sulphate and sealed shut, allowing every surface in the building to become covered in a thick layer of deep blue crystals. It was a whole world, a full-body art experience replete with smells and sounds that totally overpowered the viewer. I’d never seen, or been in, anything like it. It was amazing.

But immersive art really hit the mainstream in London in 2012, when the Barbican Curve Gallery hosted Random International’s ‘Rain Room’. Apparently, it’s not enough for Londoners that it rains constantly outside, they want to get rained on indoors too. But that was the big trick: using clever technology, Random International created a room of drizzle where you would never get wet. All around you, the rain would fall, but never on you. It was a huge, blockbusting hit.

And it was all over social media, just like the Hayward Gallery’s 2014 Martin Creed exhibition with its room of white balloons, or Japanese design group teamLab’s installation at Pace in 2017, or 180 The Strand’s ‘Strange Days’ exhibition in 2018. This was art built for the social media era, designed to be posted over and over on Instagram and Facebook: a self-perpetuation art-marketing machine.

‘It’s tempting, in any case, to speculate that the popularity of immersive art grew in parallel with the increasing amount of time we dedicate to “virtual” experience, staring at screens,’ says Rugoff. ‘But the selfie factor adds another wrinkle to the situation.’

So our physical reality is being forced to compete with our virtual one – our digital lives are making us have higher expectations of our physical lives, and this is art expressing that idea. Regardless of the wrinkles, immersive art is now very, very big business. 180 The Strand now charges up to £20 a ticket, the Tate’s well into its second year of sold-out Kusama Mirror Room installations, and the Royal Academy now plays host to Superblue, an immersive-specific – and expensively ticketed – art gallery.

American critic Brian Droitcour describes modern immersive art in a recent edition of ‘Art in America’: ‘The best immersive work, like any good art, draws on historical traditions and contemporary vernaculars, melding different ways of looking and making. The new art is unlike last century’s art. That’s what makes it exciting.’

And it is exciting; it’s overpowering, memorable, often beautiful, and has led to some of the best art of the contemporary age. But when you apply the immersive approach to artists like Klimt and Van Gogh, artists who never intended for their work to be seen in this way, it becomes a lot less about taking exciting, adventurous artistic leaps and instead becomes way more about ticket sales and selfies. That’s when you know, for sure, that the immersive art shark has been well and truly jumped.