It’s late, it’s dark, and you’re at a gig you’ve been looking forward to for weeks. The floors are sticky. The music is loud. You keep getting swung side to side and you spilled half your drink on the girl in front of you. Life is good. And there it is, the flicker of the intro to your favourite tune. It’s coming.

But suddenly, you’re no longer lost in a blur of light and darkness. Instead, you’re looking at 300 phone screens, each one identical to the next, all showing a sea of more ahead. Sure, you might not be able to see the stage for love nor money, but at least your fellow attendees got some good content for their Insta story.

Yep, phones are now an inescapable part of London’s social life. You’re paying 20 plus quid for an event to watch people film it, and for some reason, everyone else is too. And how far will it go? Will it be phones the size of iPads next, so we can watch the entire thing as it happens? Fold-out tripods you can bring along to your Hampstead Heath walk? Microchips implanted in our eyeballs? Or do we rise up as Luddites, and begin smashing fellow attendees’ phones with portable sledgehammers, one by one?

Don’t despair. These might not be your only options. It turns out there’s a movement which is catching on in the capital. And the good news is it doesn’t involve destroying your mobile device – it just means putting it away for a bit. Welcome to London-gone-phoneless. Could it take hold?

No phones allowed

Been to Abba Voyage yet? You know, the one where you watch life-size ABBAtars perform ‘The Winner Takes it All’? Well if you haven’t, you might have wondered what it would be like. That’s because Abba Voyage strictly bans phones, monitored by crowd security, so you won’t have seen it on social media.

And they’re not the only ones. Last year, Mitski stopped her Roundhouse concert to tell fans to put their phones away, and Chris Martin did the same during a Coldplay concert at Wembley. Placebo banned phones at their O2 Academy gigs in November, and anyone who went to see John Mulaney at the Eventim Apollo last month had to lock their phones away in secure Yondr pouches before they could enter.

If you’re on TikTok, of course, you’ll know it’s not always like this. Matt Healey and Harry Styles have been filmed by so many fans that you can watch them cavort at home from every possible angle. Styles even took a fan’s BeReal while on stage.

Phones do so much for us, we don't trust our own memories anymore

Recent research from Virgin Media even found that nearly half of young people wouldn’t want to go to a concert if they couldn’t take photos or videos. And there’s no escaping it – nearly a third of them feel they would miss opportunities to capture memories if they couldn’t film at a gig. They just don’t want to put those phones away.

But here’s the thing. According to a 2013 study, filming an event doesn’t help you to remember it later on. In fact, it found that people who took photos of something actually had a less accurate memory of it afterwards. This is called the ‘photo-taking impairment effect’.

‘Essentially, you’re not present in the moment,’ says psychologist Charlotte Armitage. ‘So instead of smelling, hearing, sensing what is going on around you, feeling the sound vibrations, you’re staring down into a brightly lit phone.’

And when you’re standing in a crowd full of people with their phone out, you might find yourself reaching for your own without even realising. Armitage notes that the ‘peer pressure’ element leads us to think ‘they’re doing that, I should do it too’. Plus, she adds, ‘because phones do so much for us, we almost don’t trust our own memories anymore.’

Going old school

Even clubs, where we’re meant to be letting loose, can be the absolute worst for the iPhone brigade. After lockdown, Fabric re-introduced its photo ban from 1999, placing stickers over clubbers’ phone cameras as they come in. ‘People are so relaxed about it, their phone is just an extension of their body,’ says Fabric director and co-founder Cameron Leslie. East London club Fold also has a no-phones policy, as did queer sex-posi night Crossbreed before it shut down in November.

‘It’s actually quite healthy to try and tempt people to just get into the moment, rather than try and capture it through a lens,’ Leslie explains, ‘where you literally cannot capture the atmosphere and the x-factor of what’s going on.’ It’s not enforced militantly, but clubbers tend to be given a gentle reminder if they break the rules.

And it’s not just music venues giving that gentle push. For St John owner Trevor Gulliver, who just opened a new restaurant in Marylebone, phones will never, ever be part of the dining experience they’re creating. ‘It’s quite simple,’ says Gulliver. ‘I mean, we opened in 1994 so it was a different world. It wasn’t quite those bricks with aerials sticking out the top, but phones weren’t the media photograph camera things they are now.’

When you walk into St John, a sign on the wall says ‘no phones allowed’. ‘Simply, everyone has the right to a nice lunch,’ Gulliver explains. But when the rule was introduced in 1994, it wasn’t about TikTok and Instagram (obvs), it was simply about people ‘rudely’ taking phone calls at the table. Now, it has a whole different purpose, as customers arrive keen to document the entire meal onto their Instagram stories. Hashtag St John. Hashtag date night. TikTokers even bring mini tripods up to their tables, Gulliver notes. He gently points them to the sign on the wall.

A little privacy, please?

Of course, banning phones isn’t just about ‘vibes’. It’s also about safety. We now live in a world where picking your nose on the northern line could have you cancelled in five different countries by 10am – let alone what you get up to in the clubs. In December, someone at Fabric filmed another guest while they were dancing. The guest was unaware he was being filmed, and the video showed his face. Following its circulation, Fabric put out a statement that, among other things, the author of the video would be given a lifetime ban.

‘It’s quite simple,’ says Leslie. ‘This was about an individual who’s chosen to dress the way he’s chosen, and chosen to dance the way he’s chosen. And that’s exactly what clubs are about.’ The incident was a ‘perfect example’ of why Fabric’s policy is in place, he says. ‘When people come through the doors, they’re allowed to be just in the moment, listen to music and enjoy themselves without fear of any kind of judgement of any kind.’

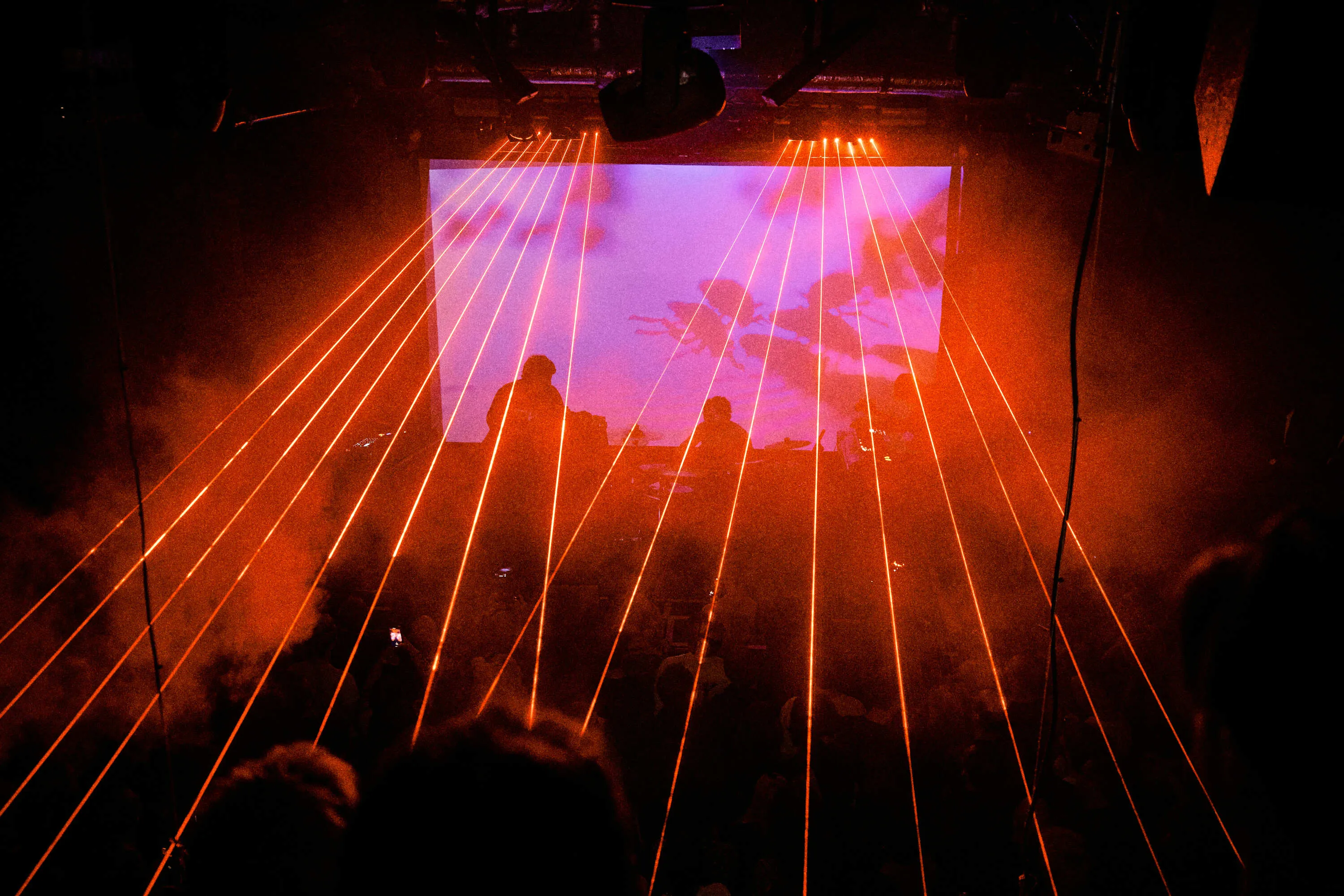

So can we expect Fabric’s policy to become the new norm? ‘It’s hard to say,’ says Leslie. ‘A lot of venues try to embrace the Instagrammable moments, a lot of those spectacles want to be captured. So it’s a delicate balancing act.’ But even if Gen Z don’t want to give it up just yet, a culture change could be on the way. And as Gulliver says, ‘You don’t go to the cinema and take pictures of the film. You don’t use it when you’re driving a car. Why use it when you’re having lunch?’