Underground origins: the 1960s

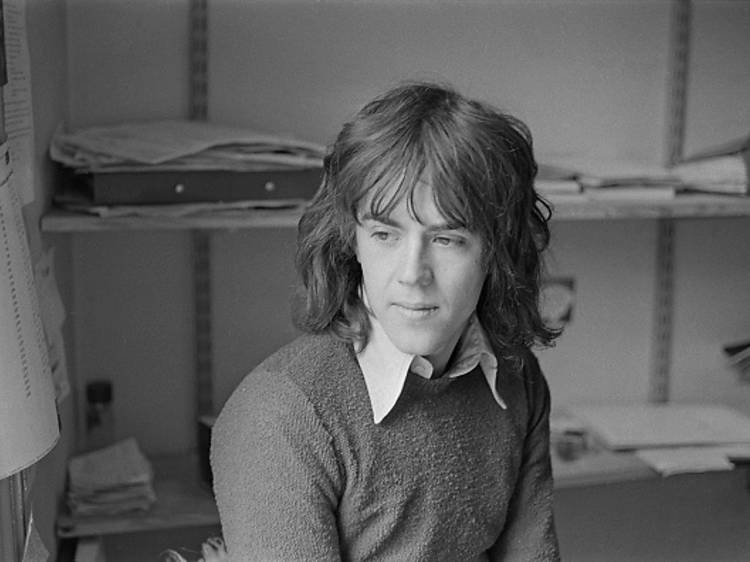

Young Tony Elliott was enrolled at Keele University in the Midlands, but spent most of his time driving his VW Beetle down to London to soak up the city’s chaotic, exploding counterculture. In the summer of ’68, after a stint editing the Keele magazine Unit, he decided London needed a comprehensive, accurate guide to all the best places to go out. After unsuccessfully offering to take over the listings page of countercultural bible International Times, Tony turned his idea into the first issue of Time Out: a fold-out A5 pamphlet, printed with birthday money from his aunt.

Issue 1, published on August 12 1968, included sections on art, film, buildings and political demos (‘Meet the Fuzz’). Tony’s girlfriend Stephanie Hughes covered theatre, shopping and ‘rabbit food’. Bob Harris (later a BBC DJ) compiled the music listings and helped Tony get the magazine seen; he and Tony distributed Time Out to hip shops around London, and sold it at the Rolling Stones’ legendary Hyde Park concert.

Soon the magazine went fortnightly. By the end of 1969, Time Out had a basement office, a small team of clued-up editors and a groovy readership of 10,000 – including psychedelic luminaries like David Bowie and Marc Bolan. ‘We were a bright light,’ said Tony later: ‘The one magazine that covered the new underground, independent culture alongside the best of the mainstream.’