[category]

[title]

The Jonathan Club’s Town Club will host two days of public tours through the L.A. Conservancy.

I don’t know how many times I’ve walked or driven past the unobtrusive brick exterior of Downtown L.A.’s Jonathan Club. And as I sat in traffic on Figueroa Street, I always assumed the members-only social club must be fancy inside, but until I was invited to take a tour this fall, I didn’t realize the degree of architectural treasures that were hiding in there.

Now average Angelenos will soon be able to gawk inside the otherwise off-limits clubhouse: To celebrate the centennial of Jonathan Club’s DTLA building, the L.A. Conservancy is hosting two days of intimate tours of the space on January 25 and 31, 2026. Priced at $100 for the general public and $75 for Conservancy members (a fraction of what a Jonathan Club membership would cost you), the 60-to-75-minute guided tour will whisk you through the interior and exterior of the club, and it includes light refreshments, complimentary valet parking and a commemorative keepsake.

L.A. is teeming with handsome spaces for the upper crust, but when I step inside the Jonathan Club for the first time, I’m immediately taken aback by how atypically L.A. it looks, like the sort of handsome old-money hideaway you might expect to see in New York City. But its closest architectural cousin turns out to be only a few blocks away: Both the Jonathan Club and the Biltmore Los Angeles were designed by architecture firm Schultze & Weaver within a couple of years of each other. The two Renaissance Revival structures even share the same ceiling painter: Sicilian-born muralist John B. Smeraldi’s masterful handiwork is all over the lobby and historic dining hall.

Though the social club itself dates back to 1895 (and technically even a year before that as a political organization), the DTLA Town Club building debuted on December 14, 1925 (the first iteration of the smaller, satellite Beach Club arrived in Santa Monica in the ’30s). Most likely named after Brother Jonathan, a pre-Uncle Sam personification of common man patriotism, the invitation-only club’s historical roster reads like a roll call of L.A. streets and institutions: Huntington, Griffith, Doheny, Lankershim, Dockweiler and Pepperdine. William Randolph Hearst, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Buster Keaton and Ronald Reagan were all members, as well. (You’re probably noticing a trend among those names: Women were restricted to a separate entrance and elevator and couldn’t become members until, in the club’s own telling, “society’s growing impatience with ethnic and gender discrimination” led to changes in the 1970s and ’80s.) Today, the club touts a more diverse membership that totals nearly 4,000.

My tour starts in the lobby, which teases all of the features that define the rest of the building: ornate wooden trims and fireplaces, colorful geometric ceiling patterns, romantic California landscape paintings and tastefully contemporary furniture. I hook past the old-school letter board that runs down the day’s events and into the wood-and-marble elevator, which ushers me up a floor to the bulk of the social spaces.

If the dark wood of the bar and restaurant areas conjure images of smoky decadence, that’s no coincidence: The Tap Room long served as a billiards room, while the Grill was a game room. (Look closely to find historical hints among the gargoyle-like figures tucked atop the dining room’s columns, some of which are holding dice.) The walls are lined with a wealth of old photos, maps and magazine covers, every single one of which ties back to a member—there’s even a QR code above every booth that’ll run down the backstories of each item. I sit down at one of the tables for lunch with a friend during my visit, and we’re surprised that the entrees barely top $30—but then I remember that this is a club where you’re offsetting that cost with monthly dues and a steep initiation fee. A previous story on the club pegs the undisclosed upfront fee around $50,000, but a representative tells me this seems more like an average of multiple membership tiers, like ones that include the Beach Club; Town Club-only initiation fees start at $9,000, and monthly dues are more akin to a gym membership.

Tucked behind the restaurant, the appropriately titled Dodger Room is stuffed with photos and keepsakes straight from the collection of member and former Dodgers owner Peter O’Malley. I’m particularly smitten with a bookcase topped with open tomes that mimic the wavy roofline of the outfield pavilions.

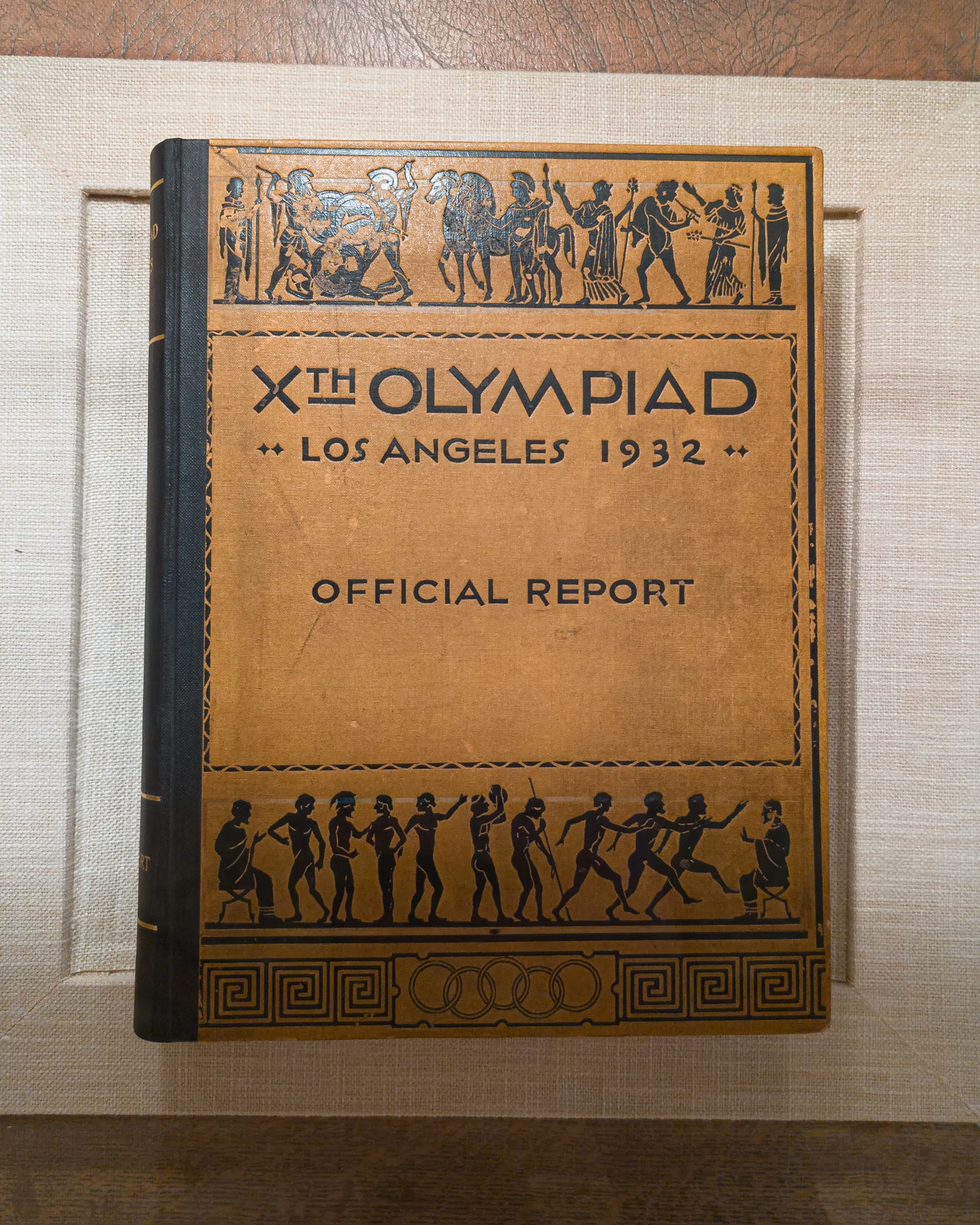

The second floor also has much quieter spaces, too: There’s a sumptuous reading room and fully functional library, a collection first approved by the club’s then-president Henry E. Huntington before he shifted all of his focus to his own San Marino estate. Wooden busts of Hippocrates, Shakespeare, Cicero and Dante monitor the space, and among the nearly 7,000-book collection, you’ll find a few prominently encased in glass, including books about the history of California, as well as an official bound report recounting the 1932 Olympics in L.A.

The most impressive spaces by far are up on the third floor: the Florentine Lounge and the Main Dining Room. I’d hold up the lounge as almost the sole reason for seriously considering the L.A. Conservancy tour: Pictures truly don’t convey the vastness of this soaring pre-function area, covered with dark wood and warm lighting fixtures. Flanking the fireplace, you’ll find colorful paintings from the early ’30s by Christian Siemer that depict the library building at the Huntington and the main domes of the Mount Wilson Observatory. There’s also an astounding 10-foot-by-17-foot canvas that shows a view of Pasadena, looking up the Arroyo Seco toward the Rose Bowl (decades before the freeway would fill that view). It’s so big it had to be craned into the space, and during my tour I’m told that it’s likely this was the largest possible canvas that could fit onto a train car (Siemer’s paintings traveled the country by rail to promote Southern California tourism).

The Florentine Lounge is only an appetizer for the Main Dining Room, which was the dining space for years but now mostly accommodates special events. It’s barely changed over the past century, though: Smeraldi murals blanket the chandelier-accented ceiling of a space that seems as fitting for weddings as it does international delegations.

I could go on and on about the rest of the building—a 12-floor establishment, as the Jonathan Club folks likely would’ve told you a century ago during Prohibition, but in reality a 13-floor building. Even today, the elevator only goes up to 12, which means you’ll need to take an intentionally roundabout route up to the 13th-floor sunroom, the most contemporary-leaning space in the building by far that balances well-preserved Batchelder tile columns with beautiful portraits of David Bowie.

As for the indoor pool, basketball court, gym, squash court and outdoor garden—not to mention the barber shop and six floors of overnight rooms—those are the sorts of details you’ll simply have to hold out for the tours to hear about.

Discover Time Out original video