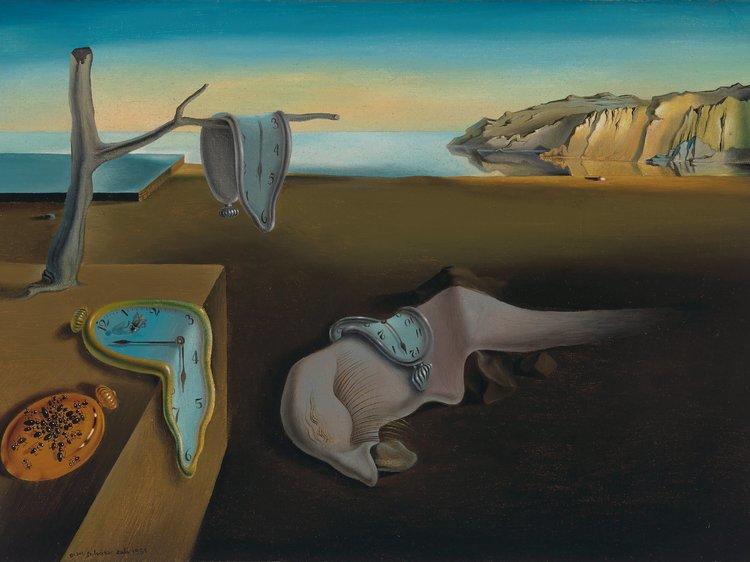

100. The Persistence of Memory (1931), Salvador Dalí

Where can I see it?: Museum of Modern Art

Dalí described his meticulously rendered works as “hand-painted dream photographs,” and certainly, the melted watches that make their appearance in this Surrealist masterpiece have become familiar symbols of that moment when reverie seems to uncannily invade the everyday. The coast of the artist’s native Catalonia serves as the backdrop for this landscape of time, in which infinity and decay are held in equipoise. As for the odd, rubbery creature in the center of the composition, it’s the artist himself, or rather his profile, stretched and flattened like Silly Putty.—Howard Halle

Photograph: Courtesy the Museum of Modern Art; NY. © 2015 Salvador Dalí; Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation / ARS; New York