[title]

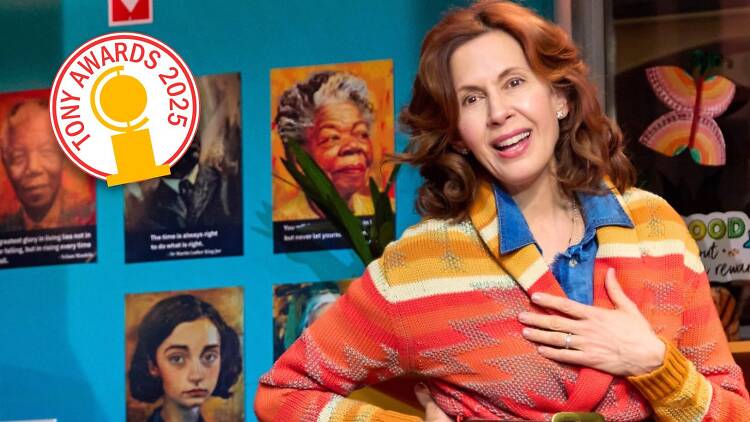

Jessica Hecht has never won a Tony Award, which is a fact so surprising that it barely even makes sense as a sentence. Tonys are not, of course, the only of marker of artistic achievement in theater, or even a consistently reliable one at all. But Hecht is not just an extraordinary actor with a unique individual style that might be described as intensely grounded flightiness. She is also a pillar in the New York theater world, and especially its nonprofit division: In a career that spans more than 30 years, she has starred in six Broadway shows that were produced by either Manhattan Theatre Club or the Roundabout, plus Off Broadway offerings by the likes of the Public, Lincoln Center Theater and Playwrights Horizons. (She has starred in commercial productions, too, like 2010's A View from the Bridge, opposite Liev Schreiber and Scarlett Johansson, and 2015's Fiddler on the Roof, opposite fellow stage treasure Danny Burstein; TV fans may know her from her recurring roles as Susan Bunch on Friends or Gretchen Schwartz on Breaking Bad.) In her spare time, she serves as the executive director of a nonprofit operation of her own: the Campfire Project, which provides arts-based therapy for displaced people in refugee camps around the world. Her third Tony nomination is in the category of Best Featured Actress in a Play, for her unforgettable performance in Eureka Day as a staunch antivaxxer at a progressive day school. We spoke with her in depth about her approach to acting, her favorite roles and what it was like to work with Arthur Miller.

In advance of the Tony Awards on June 8, Time Out has conducted in-depth interviews with select nominees. We’ll be rolling out those interviews every day this week; the full collection to date is here. Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

RECOMMENDED: A full guide to the 2025 Tony Awards

I feel like you have an idiosyncratic, personal approach to naturalism. I don't want to bore you with praise, but one of the things that I love about your work is that you seem to have a set of performance priorities that you bring to it.

That's such a wonderful way of putting it—“performance priorities” is such a thrilling thing to say. I do feel really strongly that people need to hear the language and hear the story. Sometimes you’re doing straight-up naturalism—a great Coen Brothers film or something, or the way Annie Baker writes, which is awesome—but not every play is going to be that. I think the older I've gotten, the more I'm interested in creating something that allows you to carve out space for people to really hear what's going on.

That touches on two qualities I associate with your acting. One is that your articulation is often careful; in Summer, 1976, for example, I started hearing the particular way that you hit certain words. And I also feel like you're unusually attentive on stage—I can feel you listening. Are those things that you think about when you're putting together a performance?

I do. There's a quality of being on stage that is, of course, heightening what your responsibility would be in life in a conversation. But I was trained by the greatest writers of the 20th century, Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller, who wrote with an attention to the way people engage in real conversation: how they'll take a word from the other person's dialogue and repurpose it for their own use. Williams does that a lot—the language volleys, and when that happens it is usually a sign that the two people are listening to each other, or they couldn't share that language. I'm super interested in how playwrights do that, and I like to play around with that when I'm acting—and also it takes my attention off myself, because I have a lot of stage fright. When I say that, people are like, “Oh my God, you seem so crazy and free!” But it takes me so much to get there. I feel very anxious. If I take my attention off myself and listen to the way the language is working, it's much more fun. If somebody hands me a word in a unique way that day, I can play around with it right back. It keeps my mind alert to new things I can pick up.

I’ve found that when you’re playing characters that can look adversarial or testy on the page, you tend to come at them from surprising angles. In Eureka Day, for instance, your character Suzanne has very strong convictions, but she arrives at revealing them in…not a sneaky way, exactly, but—

Sort of through the side doors.

Through the side doors. Even when she’s being intransigent, she seems very open and accommodating. Is that an intentional strategy on your part—to soften things or go around them?

These questions are really making me reflect on what's interesting to me. The things that are interesting to us relate to our own aesthetic and also just our own pleasure in life. I love little kids. Anyone in my family can attest—they’re constantly saying, “You are going to get arrested staring at these children.” [Laughs.] And when my kids were little, I loved being in their school. So when I read the play, I immediately thought, Oh my gosh, she just loves little kids. If someone is going to devote that much time to a school that is that beautiful, and to idealize childhood in such a way, she must love children. So I created a character around my own desire to be around small children. It’s not really woven in there linguistically, but the language fit beautifully into a framework where Suzanne was often explaining everything to a small child, thinking that a child would really be interested [laughs]—it's insane, but it’s the way she navigates the world. And that was definitely supported in the script: She goes about her business until she just can't anymore, and then she becomes very coarse. She can't handle life. And also it seemed to work that since her child had had such a tragic destiny, she was stuck at that moment in time. I think most people are arrested at a certain point in their life. Once I was talking to my therapist about a family member, like, “Oh my God, I don't know that we'll ever get to this evolved place that I would hope we would get to.” And my therapist said, “Don't you realize that most people aren't interested in taking a journey with you? They just wanna get through the day. They just wanna feel basically okay.” So when I look at characters, I often think about how evolved they are. Where is their evolution headed, and where did it maybe stop?

I was interested to see that you went from Eureka Day into something completely different just six weeks later: A Mother, at Baryshnikov Arts Center, which you also co-conceived with the playwright, Neena Beber.

I feel very lucky in terms of the work I get to do. But there are things I've wanted to do for a long time that I have not felt able to muscle into reality, and it feels like a now-or-never moment for me. You create enough theater that you finally think, I should trust my instinct and know what I'm interested in and just make a few things like that. [Laughs.]

The play is an updated version of Bertolt Brecht’s The Mother, which is a fairly obscure play. What drew you to this project?

I run this organization that does work in refugee camps around the world, and we were consistently struck by the mothers in these refugee camps who feel completely overwhelmed with their kids' lack of a future. When I returned from our first trip, I was at the Strand, and The Mother jumped out at me. It was one of those plays—I don't know if you studied theater as a kid—but when I was in high school, I had this teacher who would introduce us to plays far beyond our emotional or intellectual understanding.

We did Brecht’s St. Joan of the Stockyards at my high school! Kudos to our drama teacher, Mr. Meyer.

So you know exactly. And you think, What are they up to? But in reality, they're planting this little seed. When I saw that play, it suddenly overwhelmed me with a sense of the meaning of what Brecht was doing—that these stories are appropriate for multiple times in one's own life and multiple historical and social contexts. War and strife will continue to plague us, and every time you look at these plays, you can adapt the story to what's going on for you. I was coming back from a very despairing refugee camp in Greece during the height of the Syrian civil war, and at first I wanted to adapt the play to speak to that crisis, but then I sort of adapted it to speak to who I was and my sense of theater as a vehicle for telling stories. I was gifted in that experience to have Misha Baryshnikov running an institution that is all about allowing artists to have a laboratory—rather than what we're used to, which is the pressures of commercial theater.

It’s useful to have a foot in the commercial world, though. Even after decades on stage, you surely encounter people who know you only from Friends and Breaking Bad.

Yeah. And I don't watch TV that much! I feel very embarrassed that I didn't watch Friends very often. Early in my career, I was even more uncomfortable watching myself, so I don't really know the episodes at all. But I thought the actors were amazing. Lisa Kudrow is one of the most talented women I've ever encountered. And Matthew Perry was the kindest. I mean, they all had remarkable gifts. But when people talk to me about stuff, I'm so ashamed—I don't even know the storylines. And Breaking Bad was a whole ’nother moment. I'm very lucky to have done shows that were enormously successful. And I was there at the very beginning and the very end of both of those. It's this bizarre gift I was given.

I also enjoyed seeing you pop up on The Boys as the Deep’s psychotherapist. That kind of part is great for an actor who’s the right kind of listener.

If you're the right kind of listener, and also if you don't put too much weight on things. Particularly if you get onto a show early. I think of going onto these TV shows or films that are unknown entities as being a helpful player in their process. [Laughs.] On The Boys, I kept thinking, “I just wanna do a nice job for them, because they have to have something to balance all this depraved superhero stuff out.” You just walk in like you're going to do a reading of something that might be lovely. And then you never know what'll happen and you don't have to put too much pressure on it. Also, I come from a whole family of mental health workers. My dad was a psychiatrist. My sister's a psychiatrist. My mom and my sisters are therapists.

Same! My dad's a psychiatrist, and my mom's a therapist and social worker.

You and I have got to meet and talk about that at another juncture. Where did they work?

In Montreal.

In Montreal! Oh my God. I love Montreal. My grandmother and all her siblings were at the Baron de Hirsch orphanage there, which helped so many destitute Jewish kids who came to Montreal. Baron de Hirsch was a big name in the Jewish community—this incredible philanthropic man. Montreal has a history of helping. And also, my husband says the best bagels are from there.

Speaking of Jews, I saw you in Neil Simon’s Brighton Beach Memoirs, opposite Laurie Metcalf, and I thought it was wonderful. I was sad that it closed so quickly.

That was awesome. My mother grew up in the same neck of the Bronx as [producer] Manny Eisenberg and Manny’s dear sister who just passed away, Cookie Eisenberg—my mother went to school with her. And Neil really had a lot of roots in that area, although he’s known for being from Brooklyn. My mother was originally from Brooklyn, so that whole world of immigrant Jews trying to find their way was super familiar. Historically, Neil didn’t usually cast Jewish women in those parts, but somehow I slid in. And I felt like I had to very delicately play my Bronx 1937 card or whatever it was. But I knew it in my gut. That was a fascinating thing—not to make a caricature of the people you knew, not to blow it up too much, which is always very difficult if you know someone. And Neil was there in the room, and Manny, who I think is one of the greatest minds of the American theater. But also acting with Laurie Metcalf is utterly thrilling. It’s like a sporting event in the best way. You have to get it right—you come right back and try to meet her incredible depth and energy. I loved trying to do that with a character who was slightly blind. And that was my first experience with [director] David Cromer. He had just arrived from Chicago, and he has a magnificent storytelling technique, which also inspired me deeply. Later I did Streetcar with Cromer at Williamstown, with the truly great Sam Rockwell.

I’m always struck by how allergic to sentimentality Cromer seems to be.

I love that you said allergic. He is.

He has a horror of it.

Horror! “Why are you crying? Why are you crying? He died. Come on, move forward.” He has that great phrase: “Just do what a person would do.” Which is true. And he does have an extraordinary mind for storytelling. That’s sort of like what we were talking about at the beginning, about how you think I manage the language. I just want people to hear what the words are so they can have a relationship to the language, to the story, and not just to me. Cromer has an impeccable way of looking at the information the audience needs, rather than letting the behavior of the character override that.

It can be hard when you’re navigating that kind of linguistic precision and delivery on stage to not have it be empty. The trick is to find something happening—

—even though you’re managing stuff. I think that is a big trick, but you know, I think we are affected by our own storytelling more than we ever trust. You don’t have to fabricate—I shouldn’t say fabricate, but you don’t have to generate as much emotion around storytelling. If you are really listening, as we were just talking about, and really trying to find the way in which you as a person are experiencing the story in the moment, you just automatically generate emotion. We do as actors, but also—think about how much emotion you go through in the course of a day, hearing something that happened in the world. If you are really organized toward your emotional response to that, you realize how much that can happen on stage if you are able to empty yourself to the simplicity of the story. The more we kind of fabricate stuff, the more distant we get from the story.

I had a really great conversation on something related to this a few years ago with Didi O’Connell, whom I absolutely adore—

[Gasps.] Goddess. Just, goddess.

—and she was doing Dana H., which was incredibly physically disciplined. [The entire performance was lip-synched to audio of a real woman’s description of a harrowing sequence of events] so there was no room for her to add any big emotional theatrics. But what was also striking is that there was no such emotional moment in the audio itself. The woman’s tone was very straightforward. And that made me think about how artificial a lot of storytelling approaches are—those moments when people are telling stories on stage or onscreen and they kind of act out the story instead of telling it.

I was just thinking about that piece literally yesterday—how she talks about that guy putting the gun up her ass, the shock that that had happened. She did have an emotion, but it was more about the…absurdity of the situation. So the audience was terrified for her. If you don’t fill in all the emotion, the audience can have the emotion of sheer terror and despair. But she’s still not even able to process it.

Right. If you’re talking about someone having a gun in your face—

Let alone in your ass!

—let alone in your ass!—you’re not behaving the way you would if someone were actually doing that to you. You’re telling the story of someone having a gun in your face, you’re navigating what it is to tell that story. Whom are you telling it to? What are their reactions going to be? How do you feel about bringing it up again? When was the last time you told this story?

Right, a story with detail. The detail of the story is what you want someone to hear, and that’s what great writing does. Not just that you were really upset; you forget that after a while. It’s so interesting. I was thinking about these stories—I don’t mean to go back to the refugee stuff I work on, but most of these kids have been tortured, and when they write their asylum statements they are desperate to tell all the details, because the accumulation of those details is why someone had to flee. It’s not that they’re sitting there crying that someone tried to kill them multiple times, it’s the detail. What Didi does, and what I aspire to do, is create enough details that you completely believe the person. That’s all! And there’s really no amount of emotional gymnastics that you could do every night the same way that would be as trustworthy as the description. [Laughs.] Does that make sense? You can’t trust that you’ll get there emotionally every night. You’d make your scene partner crazy, because it would require that they give you the same prompts every night in the same exact way. That’s so punitive. You never know what the person opposite you is going to be capable of! We’re human! We don’t know! We’re going to be doing a hundred shows, two hundred shows!

You’ve been in three Arthur Miller plays on Broadway: After the Fall, A View from the Bridge and The Price. Miller's language is generally less poetical than that of other playwrights whose work you've done in revivals, such as Shakespeare and Tennessee Williams. How do you make that language sing?

That’s a great question. He wrote many of his plays to approximate authentic human speech. He was super interested, particularly in A View from the Bridge—he would go to those places and really try to write out what he thought people were doing, with a kind of literal justice to the way language worked that he was hearing. Your responsibility to that is enormous.

He was still around when you were doing the revival of After the Fall, right? [After the Fall is Miller's 1964 play about a Miller-like writer and his Marilyn Monroe–like wife.]

Yes. He was there for After the Fall, and he didn’t like that we had books about Marilyn on the table. Carla Gugino played Maggie [the Marilyn part] and she was stunning. She’s a magnificent actress, and she’s a deeply thoughtful actress and person. Even though she’s often cast in parts that create this goddess-like impression, her whole thing as a person is about connection. But yes, Arthur was with us, and that was life-changing. I auditioned for Arthur several times before I got that job, for different things. And he was always so kind. He would say, “We’re going to work together at some point.” As I said, I get nervous a lot, and many times I’ve literally had to talk to myself—when I’m in a situation where somebody much less brilliant than Arthur Miller is telling me how a scene works, or telling me I’m coming up short, I think: Just calm down. I figured out something with Arthur Miller. I will figure it out. It just breaks my heart thinking about him. He suffered from such a feeling of—I love that documentary his brilliant daughter Rebecca made, about how much he focused at the end on critics and what he didn’t succeed at doing, and how they didn’t really always get him. Isn’t that funny?

Authors’ relationships to their own work can be so fraught. I have a weird relationship to that, obviously, as someone who writes about people’s work. Sometimes I’ll hit on something that is exactly what they were trying for, and sometimes they’ll think I got it wrong. And sometimes maybe I did get it wrong! But also maybe sometimes I’m seeing what they did in a way they aren’t seeing, because they’re too close to it—where someone doesn’t realize that what they’ve written reveals something about them, or that it operates in a way they didn’t intend. And Miller was always cagy about the autobiographical elements of After the Fall even though it’s obviously autobiographical. But maybe a public denial can be necessary for the thing to happen at all, because otherwise it’s too lurid.

It’s like what I said about becoming a caricature of yourself if you're playing your mother or your sister or your cousin—someone you really know. I think he was cognizant of his own life being seen in a two-dimensional way, because people think they can read a book about him and then play him, and then they often play him with less complexity than he had. That was probably his biggest fear: that we’d do research by reading Timebends rather than just looking at the language of the play. He wanted very badly to put things into simple terms for the actors doing his work. In After the Fall I played Louise, his first wife and the mother of two of his kids. When we were working on that play—and he knew we had all read Timebends and this and that—he said: “Look: You’re such a nice wife, and you made a beautiful dinner, and every night you do the same, and you get everyone organized, and your husband is never on time. And you have this beautiful dinner, and this night was particularly special.” And you’re like, Oh, okay! [Laughs.] I don’t need to think about your wife. I’m a mom with two kids and a husband! I understand what it means to feel, like, “Where the fuck are you? I made this dinner.”

You’ve had the chance to work with a lot of great living playwrights—not just Miller at that time but also people like Richard Greenberg and Sarah Ruhl. Is it better or worse to work with a living writer?

It depends on the living writer. It depends on how difficult it is to simplify what you think will work with that writer. If it’s someone as clear-thinking as Miller, at a certain juncture in his life where he knows how things work for him and how to talk to actors, then you reorganize yourself and say, “I can fulfill this mission of simplifying things.” If you’re dealing with someone who has a more elusive sense of what they want, and you can’t figure out how to get that from them, that’s really challenging. Someone like Sarah, who is an exquisite writer—if you just follow the poetry of what she’s doing, very simply, and try not to manipulate it into a different frame, then you’re fine. It’s all about trying to codify—for yourself—how to do different writers’ work. It’s not going to be the same. Each writer is different, and that’s the puzzle of working with a living writer who has an aesthetic you appreciate but you don’t know how to do it yet.

Another Broadway performance of yours that I really treasured was in Greenberg’s The Assembled Parties. A friend of mine who knows her work well said he felt like you were channeling Jill Clayburgh in that one. Was that something you had in mind?

It actually was. Because she died right around that time. Rich is just peerless in his work, and I am so fond of his writing. And we were doing a reading of My Mother’s Brief Affair, and he had written it for Jill, which was before Linda [Lavin]—bless both of them—before Linda took that part. And Jill had a quality with his writing that was unlike anybody I’d seen. She didn’t know the charms she had, when she was reading or being. Maybe it was because she was sick, too, and was just trying to get through the reading without causing any waves that might make her feel unwell. But I thought she was so graceful. I didn’t know, but her grace was definitely something that influenced me. And Rich was very fond of her. So, yeah. She was magnificent.

Okay, I have one more question for you, but it's a two-part question. When you look back on your stage career, what part would you want to go back and do again because you had such a great time doing it, and which part would you want to go back and do again because you think you would do something differently?

Oh, beautiful. The one I would wanna go back and do again, because there might be new things to be revealed, is this play called Stop Kiss [by Diana Son]. That was my first big success.

This was at the Public in the late 1990s?

At the Public, yeah. I relied a lot on my own, for lack of a better word, “quirkiness” at that time to figure out how the language worked in a way that was seamless—so that when there were all of these different things going on there was still a seamlessness to it. It was the first time I felt like, “Oh, now I can do multiple things at once, and go from a serious scene to a funny scene. I know how to do this thing, and I didn't know I knew how to do this thing before!” But I would like to do it again with my head screwed on a little bit better, with more precision and less abandon. I was also pregnant when I did that play, so it was a little bit overwhelming.

Is that the one where the Times critic compared you to Sandy Dennis?

Maybe? Or that might’ve been—because it’s funny, I genuinely stay away from reading reviews, but my mother still gives me a sense of things—and that might’ve been Rich’s great play The House in Town, because she said, “Well, they didn’t really like what you did, but they said it was because you were too much like someone I think is very talented, Sandy Dennis.”

No, this one was a compliment! I guess you were compared to her in two Times reviews.

So not just a fail! And I like Sandy Dennis. I remember Joe Mantello once saying that one of his favorite actors was Sandy Dennis, and I was like, Oh, good! [Laughs.]

She was great in the right part! I just saw Another Woman again, the Woody Allen movie, and she has only two scenes but she runs away with that movie. That scene in the restaurant booth is just amazing.

Because she found this little portal. She was more of a Method actor, but she would find a little portal, and then you were like, Oh my God, nobody would figure that out besides you.

And what about the part that you would like to do again just for the pleasure?

I would want to do Blanche again [in A Streetcar Named Desire], although I'm obviously far too old. I would want to do Blanche again because the specificity of that language—to be able to speak that again… I teach that play, and I sometimes think of the language of Blanche as just a bible for one’s existence, in terms of why I act, and why people get lost in life. David Cromer explained a lot about that play when he said, “Blanche and Stanley are two very, very capable human beings, real survivors. Stanley has had very good luck, and Blanche has had terrible luck. She's not just crazy. She's had horrible luck.” I think about how people survive with terrible luck. And I think it's such an interesting task as an actor to figure that out.