[title]

"Let Me Tell You" is a series of columns from our expert editors about NYC living, including the best things to do, where to eat and drink, and what to see at the theater. Last time, Things to Do Editor Rossilynne Skena Culgan explored why cemeteries are hosting the coolest events in NYC right now.

After becoming pregnant this spring, I quickly realized this wouldn’t just be a journey of my body and emotions—it would also be a journey of stuff. Well-meaning loved ones sent me long lists of my must-have items and shared strong opinions about what brands I needed for my baby to live her best life. As an eco-conscious, minimalist New Yorker living on a tight budget in a tiny Manhattan apartment, this freaked me out almost as much as the prospect of birth itself.

That’s why when I heard about the new exhibit “Designing Motherhood: Things that Make and Break Our Births” at Museum of Arts and Design in Columbus Circle, I knew I had to go see it. The fascinating exhibition covers 150 years of how design has affected everything from menstruation to motherhood to menopause—and how all of these phases interact with products, programs and policies. “Designing Motherhood” goes beyond biology and gender to explore that while being born is a universal human experience, the designs that shape that experience are not.

RECOMMENDED: The best museum exhibitions in NYC right now

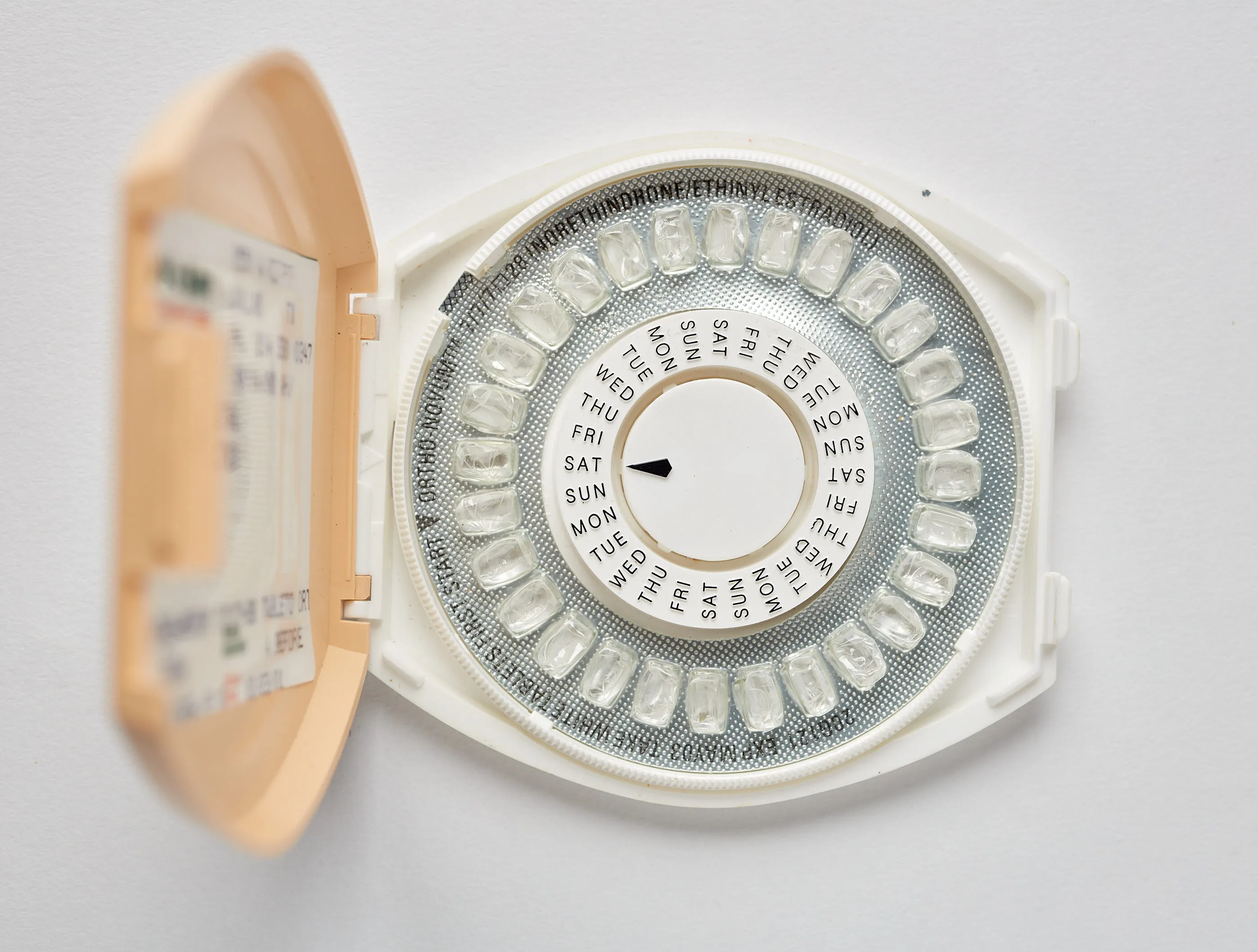

The exhibition, which is part of the Designing Motherhood project and co-organized by Elizabeth Koehn and Alexandra Schwartz, begins with conception and fertility. Whether we’re trying to conceive or actively trying not to, products such as CycleBeads, ovulation predictor kits, Plan B, IUDs, birth control pills, condoms and insemination devices play an important role. You’ll see the evolution of these products over the years, coupled with the powerful text by Gabrielle Blair titled Ejaculate Responsibly: A New Way to Think About Abortion. As she writes, “Ovulation is involuntary. Ejaculation is not.” Her book underscores the unfair burden placed on women when it comes to preventing pregnancy, considering that 90% of the birth control market targets women.

In my privileged middle-class American experience, I know many women—myself included—who spent their 20s trying desperately not to get pregnant and spent their 30s trying desperately to conceive. It was fascinating to see so many of the devices that make that possible every day.

Eventually, once sperm fertilizes an egg, babies live in a protective womb for 40 weeks of pregnancy, getting everything they need from mom and living blissfully unaware of the capitalist system they’ll soon enter into. From their first cry, their entry into that system quickly changes. When babies are born, they’ll require some basics, of course, such as diapers, clothing and feeding supplies. Some societies, like Finland, provide “baby boxes” with all of these essentials given for free to all expectant Finnish citizens, curators explain. Many European countries have followed suit.

The United States, however, where approximately 50% of families struggle to afford diapers, has not. Some individual cities and aid organizations have stepped up to help, including New York City in partnership with Welcome Baby USA and the United Way, which offers baby boxes at select hospitals. Additionally, since 2020, local organization Saving Mothers also offers kits to expectant mothers in New York City; those kits even include sample scripts to help women confront structural racism and sexism within the healthcare system.

I know many women—myself included—who spent their 20s trying desperately not to get pregnant and spent their 30s trying desperately to conceive.

You can see an example of what a baby box looks like in the exhibition. Packed with onesies, socks, books, a thermometer and more, these kits have the power to make a major difference.

As the exhibit continues, it showcases newspaper clippings announcing hospital innovations, activist posters about reproductive rights, maternity clothes and videos of midwifery care appointments. Lactation and breastfeeding get a spotlight, too, before the exhibit turns to what the museum aptly calls “the baby gear industrial complex.”

As the curators explain, “the baby gear industry is big business, especially thanks to online marketing algorithms that can target expectant parents from the moment they purchase an ovulation kit.” As somebody barraged with Instagram ads for everything from the Babybub maternity pillow to the wonders of the Babylist registry, that really resonated.

Ads tend to capitalize on new parents’ anxieties, as the exhibit explains, insisting that their product will make the parents’ life easier and the baby’s life safer. As someone who spent hours researching the best, safest, most eco-friendly bassinets, carriers, strollers and more, I get definitely feel that anxiety. The constant touting of “new and improved” offerings isn’t just expensive and overwhelming, it’s a sustainability nightmare.

To explore that concept, there’s a towering wall of strollers, from retro models with pastel colors and big wheels to today’s sleeker options. Another display debates the merits of the $1,700 Snoo. Further, you’ll learn about competing items on the market—from the $25 IKEA plastic high chair to Stokke’s wooden Tripp Trapp Chair, which retails for $250. I have personally waded into the high chair debate and learned that many people have strong opinions about where my future baby sits to eat—and the price tag, sustainability and design merits of that particular seat.

I’m not technically a parent yet, but from the very first positive pregnancy test, the safety of my baby was my primary concern.

The exhibit ends with a note about safety. Before the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission was established in the early 1970s, child product safety was a hodgepodge of local regulations, consumer awareness and industry self-regulation. The federal commission’s safety recalls made kids safer by decreasing injuries and deaths. But, curators warn, recent federal funding and staffing cuts have left the fate of this agency uncertain.

I’m not technically a parent yet, but from the very first positive pregnancy test, the safety of my baby was my primary concern, and safety is no doubt a universal concern for parents across the globe. “Designing Motherhood” showcases the gains we’ve made in safe, smart design—and the big consequences for our little ones if we let that slip away.