1. “Rose’s Turn” from Gypsy (1959)

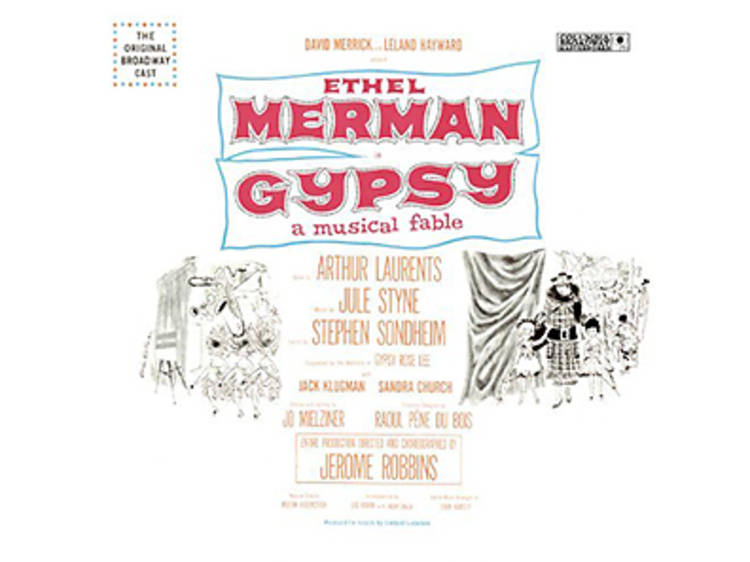

Throughout Gypsy, Mama Rose has pushed her children to be stars, even if it meant pushing them away from her. But in the show’s shattering climactic number, she finally takes center stage herself, if only in her mind. Built from fragments of prior songs in Jule Styne and Stephen Sondheim’s classic score, this musical nervous breakdown—created by Sondheim and director Jerome Robbins in an inspired three-hour improvisation—takes Rose apart and reassembles the pieces into a sad and scary portrait of thwarted drive; the strenuous optimism of “Everything’s Coming Up Roses,” her first-act finale, twists into the unquenchable need of “everything coming up Rose’s.” It’s a feast for actors; no wonder the top leading ladies of their generations, from Ethel Merman and Angela Lansbury through Bernadette Peters and Patti LuPone, have yearned to take their turns at it. As often as it’s been wrung out, the song remains inexhaustible.—Adam Feldman