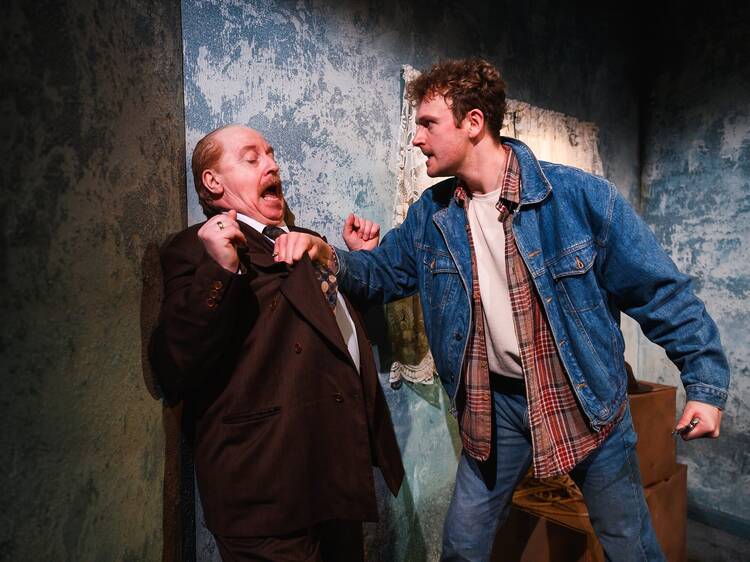

Anya is a London-based freelancer but her hometown of Birmingham will always be where her heart lies. She spend a lot of her time at the theatre and thinks Thursday is the best day of the week.

Anya is a London-based freelancer but her hometown of Birmingham will always be where her heart lies. She spend a lot of her time at the theatre and thinks Thursday is the best day of the week.