[title]

★★★★★

Ivo van Hove is a nothing-if-not-mercurial director: his last London outing was the much derided (though I liked it) avant-garde ‘musical’ Opening Night, which was about as big a flop as you really get in the West End these days, closing weeks early.

But expectations were always high for this revival of Arthur Miller’s 1947 breakthrough All My Sons, because Van Hove made his own UK breakthrough with his extraordinary 2014 production of Miller’s A View from the Bridge. And by Hove, he’s done it again.

To some extent the secret of his triumph here is ‘cast really really good actors’, foremost Bryan Cranston and Paapa Essiudu, who offer two of the best stage performances of 2025.

But what van Hove has done is discretely uncouple Miller’s play from the naturalism that often stifles it. Running at the same length as the starry Old Vic production of a few years back but with no interval (ie about 15 minutes longer), Van Hove’s production really savours the writing.

All My Sons is an eventually bitter indictment of the American dream, that traces the downfall of Joe Keller (Cranston), a businessman and factor owner in suburban Ohio, 1947, who has recently avoided jail for his business’s role in selling cracked cylinder heads to the US Air Force, leading to the deaths of 21 pilots (yes, it’s what the band is named after). His partner Steve Deever was instead blamed and jailed.

When I’ve seen the play before, the production has tended to gallop towards this part of the story, with a focus that minimises the characters who aren’t members of the Keller family. But Van Hove luxuriates in every detail and role. The matter of the dead pilots doesn’t emerge until some way in, allowing the initial phases of the play to unfurl as a quirkily poignant study in how sedate suburban American life was scarred by the war. Here, the Keller’s negotiate with their oddball neighbours and grapple with the aftermath of their pilot son Larry’s disappearance at the height of the conflict. Relatively minor characters get stunning scenes: in particular the arrival of Steve’s son George – who can be little more than a deus ex machina to usher in the play’s climax – is handled phenomenally well. Looking like he slept in a hedge, Tom Glynn-Carney is superb as George, from his wildly disruptive entrance to a usually fleeting encounter with his now married former love Lydia (Aliya Odoffin) that plays out like a full-blooded drama of its own.

By Hove, he’s done it again

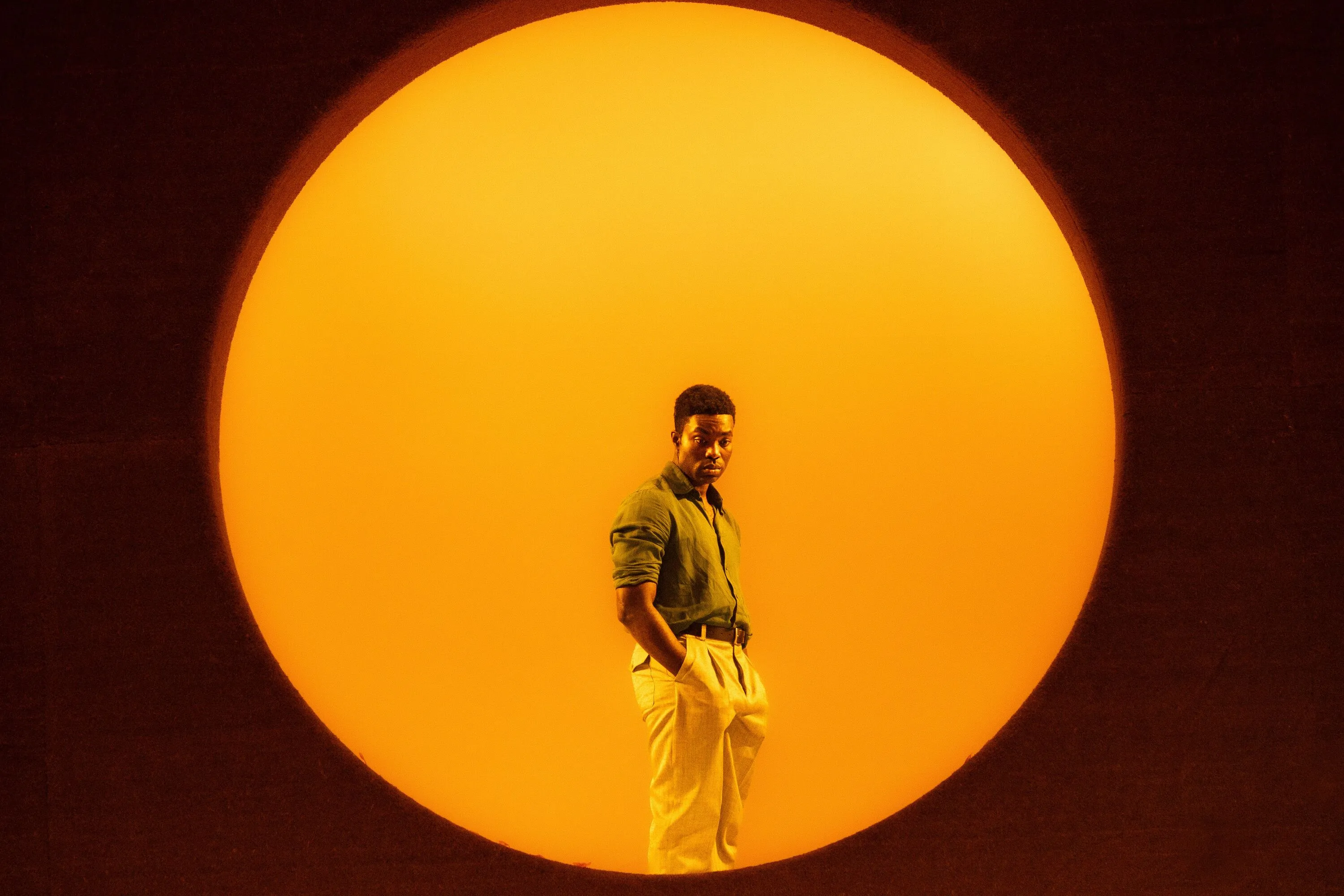

Van Hove stages All My Sons like a series of playlets that flow into each other, the central drama slowly building to a climax but with each component given its due. It’s bound together by an extraordinary creative team: Jan Versweyveld’s evocative set simply consists of the apple tree planted in Larry’s memory that is topped by a storm at the start of the story, a round aperture behind it standing in for the Keller’s house. Tom Gibbons’s minimalist but ever-present score drifts from quirky to sanctified to chilling, heightening every scene. And Versweyveld’s lighting is astonishing, starting out warmly naturalistic – a perfect sunny morning in the suburbs – but gradually becoming further and further unmoored from reality as the drama intensifies, the final scenes unfolding under sinister, unnatural greens and blues.

But it’s the actors that ultimately make it. Cranston is superb as a grandfatherly figure who believes he has squared his past actions with himself, because he’s a pragmatist, a capitalist and because he thinks what he did was in line with the American Dream. But at the very end he is almost physically stunned to discover that he does care – the revelation rips him to shred before our eyes. Marianne Jean-Baptiste is exquisite as Kate Keller: a tough, no nonsense woman for whom the death of her son Larry has become an achilles heel, a point of vulnerability in an otherwise steely character.

It’s Essiedu however, who really runs off with the show as the Kellers’ surviving son Chris. At one point the family’s embittered neighbour Sue (Cath Whitefield) suggests Chris leave town because she’s annoyed that his sunny goodness is encouraging her husband to take a lower paid job (‘He's driving my husband crazy with that phony idealism of his’). And as Chris, Essiedu really is that guy: a puppyish, bashful, extraordinary wholesome young man who teeters on the border between ‘really nice’ and ‘living saint’. We really root for him – when he eventually turns on Joe it’s not a petty family squabble, it’s Biblical, the Son confronting the Father and declaring Heaven is a lie. There’s plenty of imagery relating to the Fall sprinkled throughout Miller’s prose, and this production laps it up.

It’s more meandering and less taut than Van Hove’s A View from the Bridge, but I think that’s a strength in the end – he’s certainly convinced me that All My Sons shouldn’t be rushed. The whole thing plays out symphonically, building to an astonishing crescendo. Right near the end, Joe finally says the play’s name, its meaning clear at last. When I’ve seen the play before, there’s been no special reaction. Here, the audience gasped.

All My Sons is at Wyndham’s Theatre, now until Mar 7 2026. Buy tickets here.

The best new London theatre shows to book for in 2025 and 2026.

Sadie Sink will star in Robert Icke’s Romeo & Juliet next year.