Highams park has a secret. The suburb, which lies just above the north-eastern cusp of the North Circular, might seem sleepy and unassuming – there’s a big Tesco, a Screwfix and rows of duplicate detached houses – but it’s actually home to something much more unusual.

Lyle’s golden syrup recipe is top secret. It’s so top secret, in fact, that in order to even get access to the factory I’ve spent months negotiating and wangling my way in. It’s finally paid off – an employee of ‘Big Syrup’ has finally agreed to let me inside Plaistow Wharf, which has been making the delicious amber goo since 1885.

Nestled behind West Silvertown DLR station, the huge grey factory is easily identifiable as syrup central thanks to the giant Lyle’s can attached to the side of the building – and the fact that as you walk closer you can smell the unmistakable sickly-sweet scent of burnt sugar in the air. At the entrance, there’s a stone carving of the slightly creepy Lyle’s golden syrup logo – a dead lion surrounded by bees with the legend ‘From the strong came forth sweetness’.

The logo is something that would probably never get past advertising bods today, but golden syrup’s design has been unchanged since its inception, and the product holds a Guinness World Record for the world’s oldest branding.

Before I can get inside the factory and see how the secretive syrup is made, I visit another location: Tate & Lyle’s sugar refinery, at the other end of what was once called ‘the sugar mile’.

Local affairs manager Chris Abell meets me at the front of the refinery, which is tucked away behind a massive wall near City Airport. We change into hard hats and yellow tabards, and I remove all my jewellery, as he tells me that the company’s tin line churns out a staggering 40,000 cans of Lyle’s golden syrup a day, five days a week.

‘This means we produce over 10 million cans a year,’ he says. ‘What I like about the tins being unchanged is that I’m eating the same product somebody would have 100 years ago.’

Now mostly rows of building sites and luxury flats, ‘sugar mile’ was the UK’s hub for all things sweet in the early twentieth century, from Trebor’s mints to Keiller’s marmalade. But its sugar kings were undoubtedly nineteenth-century refiners Abram Lyle and Henry Tate. Although their two companies were merged by their families in 1921 (Lyle owned Plaistow Wharf and Tate the refinery), Abell explains that these two sugar daddies were actually bitter rivals in their lifetimes. ‘They would both get the same train from Fenchurch Street and ignore each other,’ he says. The decision to merge after the rivals died was a tactical one, allowing the company to refine 50 percent of the UK’s sugar.

Stepping inside the main warehouse at the refinery, I am greeted by an absolutely gigantic pile of unrefined cane sugar – around 50,000 tonnes of the brown stuff. I fight an insatiable urge to dive headfirst into this crystalline Everest, which crunches under my feet like snow. The raw sugar arrives in huge ships that deliver it to the jetty outside, from places such as Brazil, Mozambique and the Caribbean. Abell is keen to stress that at this stage it’s not actually edible – that happens when it’s refined into the white stuff that you might stir into a cuppa.

Some of this unrefined sugar is taken by lorry to Plaistow Wharf, where it goes through a process to turn it into Lyle’s golden syrup. After arriving at Plaistow Wharf, I learn that every drop of Lyle’s golden syrup ever produced has been made at this factory, after Abram Lyle was the first person to realise that a by-product of sugar refining could be turned into a delicious syrup. Today, only nine people in the world – nicknamed ‘Goldies’ – know the exact recipe.

The history of golden syrup is even richer than the product. The ingredients haven’t changed since Victorian times, meaning the tin in your cupboard contains the exact same stuff that was taken by explorer Captain Scott on his doomed 1910 Antarctic expedition. The Plaistow Wharf factory was targeted by German bombers 68 times during World War II but never ceased production, and even offered shelter to locals who had lost their homes in the Blitz.

As we walk through Plaistow Wharf, it’s a buzzing hive of activity as the factory gears up for its busiest time of the year: Pancake Day. In the first room I’m taken to, I see the tins being made. Machines that date back to the 1940s whizz and clank as the metal is beaten into shape and decorated with that iconic green-and-gold branding. It’s a hypnotic process watching everything click into place and seeing the cans move along the lines above my head. At the end of the line, a huge wheel covered in nozzles creates a vacuum in each tin, to check it’s fully airtight – those that aren’t drop off the production line and are swiftly carted away by the workers.

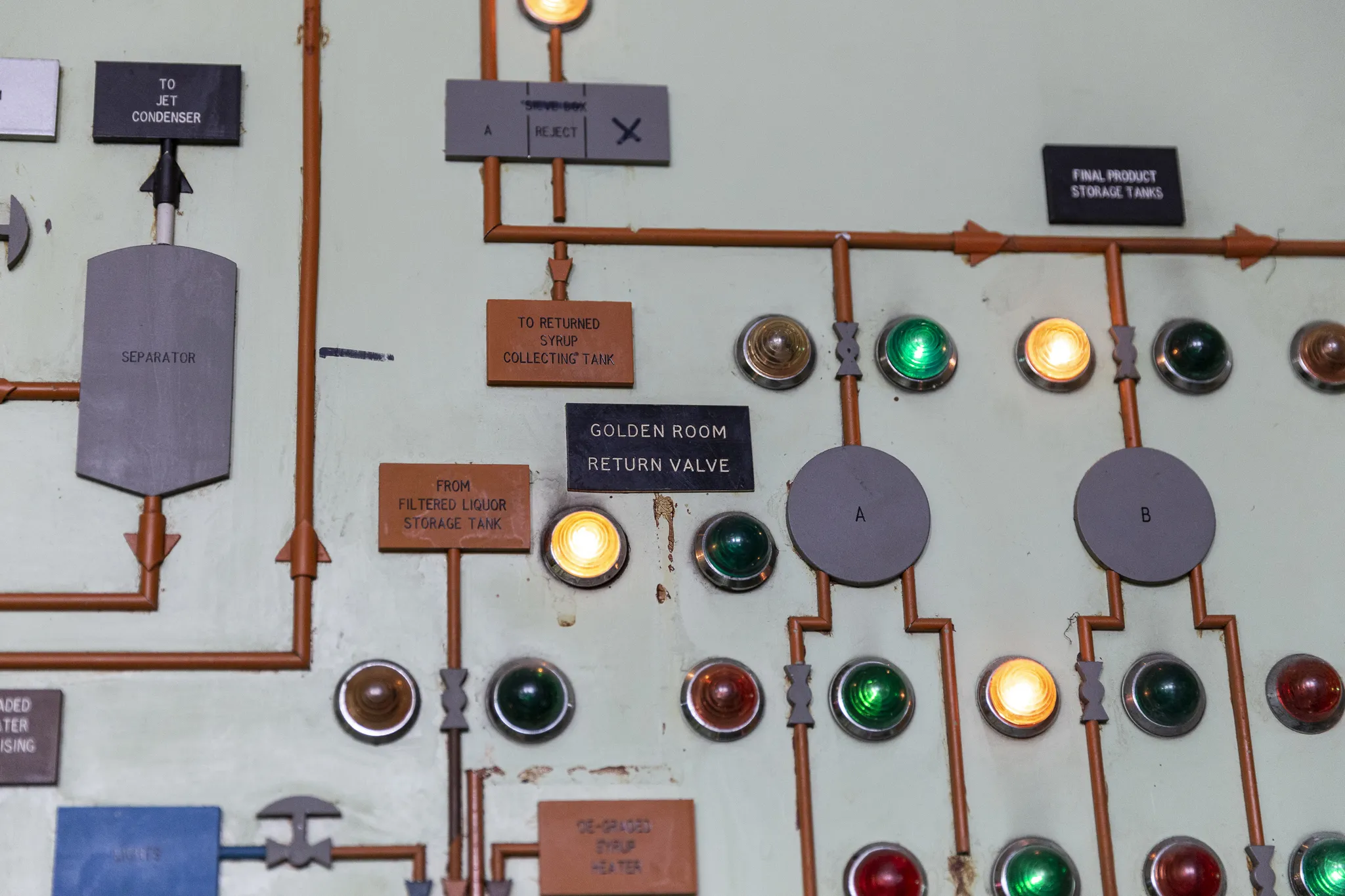

Everything is operated by a giant panel in a side control room, which Chris describes as ‘the heart of the building’. It looks exactly like Homer Simpson’s workspace. I was expecting Willy Wonka-style rivers of gold, but the factory is more like a laboratory than a fantasy sugar kingdom.

I meet one of the ‘Goldies’, Shruti Kawa, the factory’s process area manager. Despite my penetrating, Paxman-esque lines of questioning, she won’t give up the recipe, though she is able to give me some more details. ‘We take the by-product of sugar refining, a substance called “jet”,’ she explains. ‘About 100 tonnes of jet comes from the refinery every day, about four tankers’ worth. Jet is a very dark syrup that crystallises easily. We process it so it won’t crystallise for more than five years.’

The process that stops the jet crystallising creates the taste. As the colour molecules are removed, it turns from a dark red to the famous golden hue, and it thickens into a syrup. ‘It takes eight hours overall from beginning to end,’ says Kawa.

We walk into the next room, where a different machine fills each tin with syrup. The syrup is heated to 46C before pouring to make it runnier and speed up the process. Abell hands me a spoon and pulls a tin off the line, encouraging me to try the syrup right there. The delicious warm sweetness transports me right back to childhood baking.

After the syrup is poured, the cans are sealed by another machine. Although the syrup has remained unchanged from the past, the factory has adapted to the present day. In another room, modern machines pump the syrup into squeezy bottles – around 100,000 of these are made every day.

At the end of each day, the bottles and tins – more than a million per month – are loaded on to pallets, and transported all around the country, eventually finding their way into people’s kitchen cupboards and on to their pancakes.

As I leave, Abell presents me with a memento – a tin of Lyle’s golden syrup, of course. I leave on a sugar high – satisfied that I’ve finally managed to sweet-talk my way into this holy of holies. Even if they do keep a pretty tight lid on how their famous golden product is made.