William Versace is a name you should get to know. This first generation Aussie-Italian is a multidisciplinary artist who has an otherworldly ability to capture the wild, unspoken beauty of the natural world. Whether it be gelatinous resin creations, brilliant pigments handmade from native flowers, the world’s oldest form of photography – or sculptures that have been created hand-in-hand with Mother Earth herself, his art transcends human reality and touches something far deeper and more ancient.

Ever since he was a kid playing in his Nonno and Nonna’s back garden, he has been fascinated with the crazy textures of found objects and the natural world, and his current body of work is inspired by his deep affinity with the land around Kamay (also known as Botany Bay) in southwestern Sydney. This specific place was the big-time inspiration for his very first solo show; ‘Directions Back Home’, and trust us when we say that it’s pretty bloody magical.

However, life doesn’t always play nice. While feverishly preparing for his first exhibition show, William was struck by a serious tragedy, his entire studio was engulfed in a catastrophic fire. William lost ten years of work and thousands of dollars in the space of ten minutes. The fire was totally devastating, but William managed to pull through, creating an ethereal show that we think everyone should go and see. (Also, if you want to help out a young artist who's lost everything in a blazing inferno, you can donate to him here.)

Time Out sat down with William to talk about the fire, his Nonna and how he manages to capture the invisible.

How long have you been an artist? Where did it all begin for you?

The origins of my practice were definitely in my Nonna and Nonno’s backyard. My grandparents are migrants from the south of Italy, and when we were born my parents chose not to teach us Italian. My grandparents were peasants from Italy – my Nonna couldn’t even read or write, so she never learned English. We had this really weird relationship that I didn’t realise was weird.

I remember speaking to one of my friend’s grandparents in high school for the first time and turning around and being like, what the fuck – you can speak to your grandma?

My way of relating with them was very actionary and physical, so when I was at my Nonna’s place I would just go and explore the backyard – and she was like a hoarder, bro. It was one of those houses that you walk past and you go, oh fuck. I would go and explore the crazy objects and play with them and look at all the textures, it was all old and I was fascinated. And the other side was my Nonno, we couldn't talk, so what we'd do together was garden. I'd be picking potatoes, climbing up ladders for him to pick the mandarins or the plums, and that was where my art practice started, just the fascination with the objects there. Actually my high school art exhibition used a lot of materials from my Nonna’s holding stash. That was the beginning of it.

Can you describe your practice?

My practice is deliberately really broad in scope and materiality. The fundament of my practice is basically what it means to be a settler on Indigenous lands – what it means to be at home in this country. Mostly what I try to do is tell stories of place, and in this particular exhibition, I tried to let the place tell the story. I've tried to remove myself as much as I could from the process and let the place do what it does. And every place is really, really, different. So, depending on the place and what I think can represent that story the best, I will choose my material according to that.

Kamay is a big part of your work – what is it about this part of Sydney that captures you and makes you see it as worthy of attention?

To be totally honest with you [laughs], the reason I started going was because it was the quietest beach in Sydney. And no one was there, and I could be naked on the beach. I've developed this relationship with this place (Kamay) for 10 years since I moved here, and my art practice has grown with that place. The more I brought people there, and the more I created memories there, the more I spent time with the place, the more I noticed things – it was this long-form development.

Everyone I ever brought there was like, “ugh, why do you want to come here Will?” It’s right near the fucking container docks – on one side it’s beautiful national park and on the other it looks like fucking Star Wars.

There was really nothing that drew me to that place, other than the fact that I just spent time with it. It's nice that my first solo show is with this place, because it's like me leaving home and being in Kamay and exploring it with my art practice was almost reminiscent of what I used to do as a kid in my Nonna and Nonno’s backyard. It’s really special to me.

What kinds of wild and unique materials and things have you used from Kamay for this exhibition? What are the craziest things you’ve done that stand out?

There was a series of sculptures called ‘Erode’. For those sculptures I recognised that in that place (at Kamay) there were all these constant water streams that were coming off the mainland and dripping off the rocks. And I was like, oh, wouldn't it be interesting if Kamay was to collaborate with me? If I put something there – just a blank something, and just let the place over time sculpt the sculptures? I had 12 months, so I couldn’t put a fucking rock there because it would take 30 years, so I chose natural plaster (for environmental safety).

I also don’t always use the natural elements in place, especially if the place is highly anthropomorphically influenced. Botany Bay's heavily humanised, so I try not to create a picture perfect fairytale vision. There’s a golf course at Kamay. And I would notice that once every week or something, there was this [run-off] coming off the golf course [...] I was like, fuck, [there could be] chemicals and shit in this are invisible. How do I make the invisible visible?

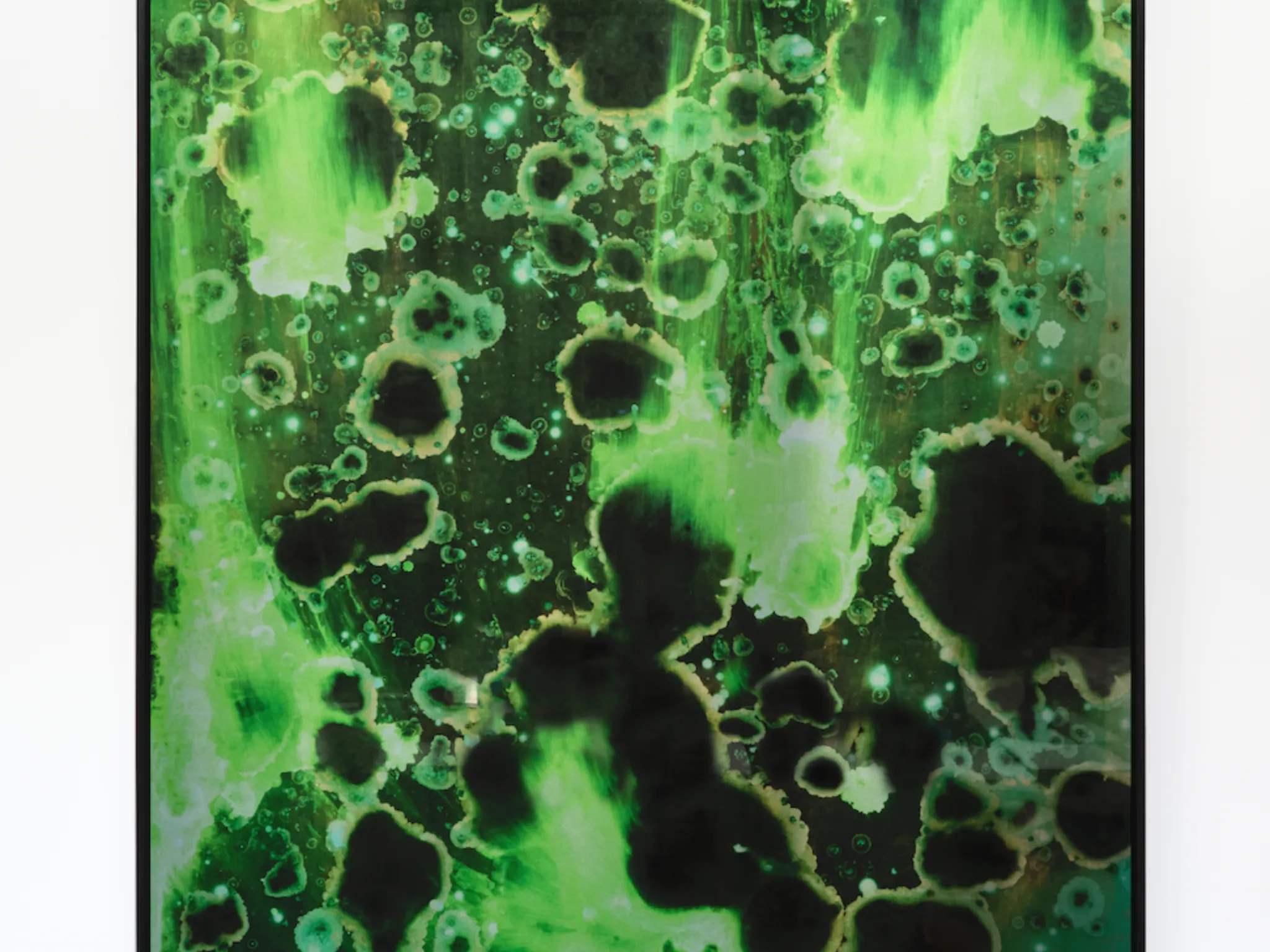

I found this process, which is the oldest form of photography. It's an experimental, cameraless photographic method. Basically these things are called photograms, and it works similar to a camera, but in photograms you’re doing it directly onto silver gelatin paper. So I took this silver gelatin paper and started putting elements from the place onto the paper, and you get these really abstract things showing a reaction to UV light, chemicals and temperature and objects. There are six photograms in the show, and some of them I put blue bottles on the paper, some of them I put seaweed, some I put run-off from the golf course. One of them's called ‘Conversations With a Rock Pool’ where I put all these elements from a rock pool; like salt, water and snails and just let the image burn.

You recently lost your studio in a fire, could you tell us a bit about what happened?

I was working on my Kamay exhibition, and I was nearing finishing. I was in the studio, it was about 10 or 11 o'clock, and I went inside to grab some stuff. And then ten minutes later I just heard; “Will, Will, fuck there’s a fire!”, and I ran out and the whole back wall of my studio was on fire. I’m usually pretty good at dealing with fire because I've had some pretty close calls in my time – but this one was like no other. And my fire extinguisher was behind the fire. So I was reaching for my extinguisher, but I was burning my arm – and I just started flapping. And obviously no one's of any use when you start flapping. I ran out, and (my friend) called the fire brigade. I grabbed the hose and tried to put it out, but it just got so big.

I remember thinking: game over. That’s it. There’s no stopping this. And then ten seconds later, everything started exploding.

Like, the batteries, my tools, spray paint cans, my gas bottles, it was like a war zone. And then something like seven minutes later, the firies came and put it out, and the photos you saw are the damage that happened in seven minutes. It was ten years of work, gone in ten minutes. Everything, completely incinerated.

What’s happened since? How have you been recovering?

I was lucky that about 50 per cent of the works weren't in there (the studio), but 50 per cent of the works that were in there were really crucial ones to the show. So those ‘Erode’ sculptures, there were five of them – and four of them got lost. I was lucky that one was still at Kamay eroding. I had a chat to the gallery, and they were like, “Do you think you can still do the show?”, and I was like “Fucking hell, I don’t know”. And then I was offered a studio by some very good friends, and I have had some very good friends help me a lot. It's just been like gung-ho for two months. And I don't know what's next, after the exhibition, but I couldn't not do it. Both for emotional reasons, and financial reasons. I’ve just lost everything I'd ever worked for. I'm already fucked enough financially, I really need to do the show – whatever the show will be.

What special things will people get to see at the exhibition?

It’s a show in collaboration with Kamay. It’s not about me. You’ll see eight works called ‘The Shipwreck Series’, where basically there was an old steamship that wrecked at Bunaabi Headland at Kamay in 1932, and over almost 100 years, the salt and the UV and the weather have all made these insane textures on the shipwreck. It’s so much an artwork itself, that the only thing I did was highlight what the place has done over 90 years. I went and took live moulds of the textures, and took them back to the studio and made these bone white plaster casts of the shipwreck. You can kinda tell it’s a ship, but what you’re really looking at is Kamay having its way over 90 years. You’ll see the one ‘Erode’ sculpture that’s left, but you’ll see a video of the place eroding the others over 12 months.

The other thing you won’t see – but you will smell. I’m obsessed with the botany at the place, and one thing I do a lot – I think it’s a vegetable gardener thing – I’ll take a leaf or a flower and I’ll crush it in my fingers and smell it. And I noticed that so much of the place had these incredible smells. And so I hit up this cosmetic chemist, named Kat Snowden, and I took her for a walk, and I was like, “I know you don't do this, but can you make a scent for my exhibition?” And she said, “Fuck yes.” So there are two separate smells. There’s a bushland smell, that’s made out of eucalypt resin and different shrubs, and barks, mushroom, a native geranium, lantana. And then as you walk through the exhibition, you'll come into another smell, and that's a more coastal oceanic smell, which we made from different seaweeds, sea urchins and also small bushland scrub, so you’ll also be able to smell the place in the gallery.

You've mentioned you're not sure what's next, but is there anything that strikes a particular kind of flame in your heart that you know you’d really like to do?

[The fire] really changed what is possible, both in good and bad ways. I feel a lot a lot less tied to the studio now, because it doesn't exist. So that could manifest as a trip around Australia, to work on another place, which is something I always had in mind anyway. I'm not 100 per cent sure.