It’s rare for Red Stitch – a theatre company that bases its reputation on expertly acted new plays from around the world, with the occasional commissioned international premiere – to do a “classic”. They mounted a production of Uncle Vanya a few years ago that was only intermittently successful, all those Russians crowded onto that tiny stage. As far as I know, this is the first time in their history that they’ve mounted a classic Australian play. It’s possible they’ve hedged their bets a little, because Michael Gow’s Sweet Phoebe is a classic that feels a little like a new discovery, given its limited production history and frankly tenuous position in the Australian theatrical canon – despite featuring a young Cate Blanchett in its original production.

It turns out to be one of the company’s more astute choices for its 2019 season launch. Certain sociological aspects of the play feel a little dated at first, but as it progresses it takes on a kind of cautionary fervour that feels super contemporary, a play very much for our times. It was an ingenious decision to hand the directorial reins over to Mark Wilson, whose own performance history – most notably in Red Stitch’s production of French playwright Catherine-Anne Toupin’s Right Now, in which he played the creepiest of neighbours – suggests a natural affinity with this kind of material.

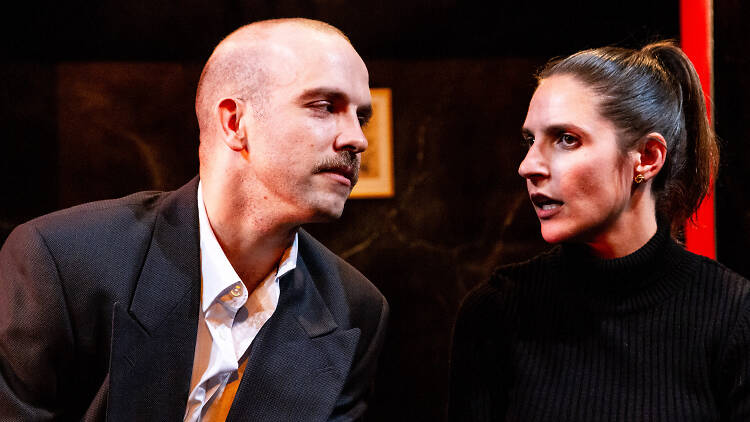

The plot is simple, the sort of clean conceit on which a good farce is founded: Frazer (Marcus McKenzie) and Helen (Olivia Monticciolo) are a power couple, driven, motivated and entirely focused on their success. The dread of performance anxiety, the hint they might not be as in control as they project, lies subsumed just under the surface. Then their friends call and ask them to take care of their precious dog, Phoebe, while they go for a week of couples’ therapy. Reluctantly, they agree.

Of course, as soon as Phoebe arrives, Helen and Frazer are smitten; they dote madly on her, relish walking her and even decide to let her inside. But when Frazer leaves the door open one morning, she runs away, and the increasingly desperate search for her starts to consume the brittle pair, to the point of utter madness. It does feel for a long time that we might still be in the realm of farce, until suddenly, as psychosis descends, it doesn’t. This massive tonal shift is the engine of the play, and Wilson brilliantly navigates it so that the precise moment the lever is pulled and comic turns to horror show is impossible to pinpoint.

The performances have Wilson’s signature all over them too: McKenzie and Monticciolo slice the air with their hands; they bottle their energy, then unleash it in wild gestures; they use their vocal intonation to ratchet up the psychological tension. He is often scary as hell, a powder keg waiting to blow. She is increasingly dejected and removed, until eventually she seems to drift away from us altogether. The two actors bounce beautifully off each other in a tortuous game whose rules keep changing and whose end is never in sight.

The set design (Laura Jean Hawkins) and lighting (Lisa Mibus) are intimidating and nightmarish, with huge slabs of black marble and angry red neon. It’s a ’90s minimalist hell, airless and subterranean. The performers move in and around its limited space like rats in a stygian tomb, as Daniel Nixon’s sound design threatens in the background. It’s deliberately symbolist and abstracted, and all the more effective for it.

Sweet Phoebe, like much of Gow’s work, is rich in allegory and imagery, and if it threatens to disappear up its own symbolism sometimes, so does Pinter and even Beckett, to which this play owes much. The dog functions here as an agent of chaos, as a kind of Cerberus of the mind whose appearance and disappearance mirror the central couple’s frail sense of self-awareness. Wilson’s excellent production, much like Matthew Lutton’s work on Gow’s Away for Malthouse in 2017, unmoors the play from its socio-realist roots and reveals its dark and bewildering heart. You’ll leave the theatre wondering if there even was a dog to begin with.