Odd. Odd behaviour. Odd rhythms. Odd connections. Odd play. Nick Coyle’s The Feather in the Web isn’t much interested in kitchen sink realism, although at times it feels like it’s flirting with it. It isn’t quite magic realism either, although there are occasional tilts in that direction, too. And tonally, it’s very hard to pin down; is it deliciously trashy, in a John Waters way, or is it slyly aggressive, like Pinter? Of course, it could be all of these things and still cohere. But it doesn’t.

It opens with a scene straight out of Waters: a cancer patient (Belinda McClory) has a friend over (Georgina Naidu) who tries to convince her of the joys of polenta cake. The cancer patient’s daughter Kimberly arrives (Michelle Brasier) and, without a hint of character motivation, shoves cake in the friend’s face and pours hot coffee over her mother. Haha. The following scene is crass in its own, totally unrelated way. Kimberly goes to a mall, where she sucks off a mincing gay makeup assistant, because that’s shocking, isn’t it? A following scene in a psychologist’s clinic is equally as silly.

It isn’t until the next scene, where Kimberly is mistaken for a waiter at a fancy engagement party, that the plot kicks in. She falls instantly in love with Miles (George Lingard), who’s marrying Lily (Emily Milledge), while Miles’ drunk socialite bitch of a mother (McClory again) looks on. This leads to an arrangement of sorts, where Kimberly does Miles’s bidding in promise for something more. Lily befriends Kimberly, they all move in together and chaos ensues.

Coyle initially seems to encourage this idea of Kimberly as a mere Mistress of Chaos, and director Declan Greene follows suit. Her first appearance is accompanied by an ominous change of lighting (Claire Springett, whose work here is generally excellent) and some death metal growling from the sound system (Tom Backhaus’s sound design makes Michael Bay seem subtle). She’s frankly sociopathic, and then a delusional schizophrenic, but the play isn’t interested much in genuine psychopathy, so neither of these modes is maintained or developed. Brasier plays her with a flat, cartoonish villainy that gets us nowhere for the first half. She tries to invest the character with a poignant subjugation in the second half, but it’s hard to see her as a real person, so the pathos never lands.

Some of the other actors fare better. McClory is incapable of turning in a less than stellar performance, and here she invests small roles with the kind of detail that makes you wish she had more to do. Milledge does everything she can to make Lily a fully rounded personality (even though she clearly should be playing the lead) and Lingard makes the utterly loathsome Miles feel almost credible.

Greene, who has taken over the artistic directorship of Griffin Theatre, where this play originally premiered, has a couple of signature stylistic quirks, which he employs here to ambiguous effect. His plays are always super loud, uncomfortably loud, and this one is no exception; from bad karaoke to awkward party speeches, everyone is miked to maximum volume, which feels like an assault much of the time. He also tends towards an insular jocularity that feels like a private joke in a schoolyard, and the result in this case is a play that feels written solely for the initiated.

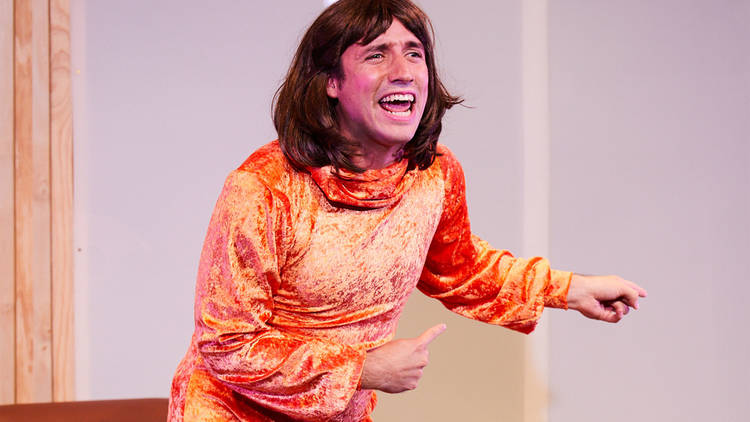

Coyle is ostensibly talking about the horror of cliques and the outsider as agent for social change with Feather in the Web, so it’s a little disconcerting to find the production so self-satisfied and unwelcoming. In the absence of a convincing lead, the actor who comes to represent the piece is Patrick Durnan Silva in a variety of jokey caricatures. A performer who comes from the world of sketch comedy, he remains so far from creating credible humans he seems to beam down from another planet.

Somewhere in all this studied mayhem is a real concern for the oddball, for oddity as a rational response to a conformist world. And Australians have always had a unique approach to highly idiosyncratic characters: you only have to think of Muriel Heslop or Dimity from Shirley Barrett’s 1996 film Love Serenade. Coyle has the makings of this kind of bizarre independent spirit with Kimberly, but he doesn’t quite pull her off, largely because those early scenes give us no context or chance to empathise. She’s just odd, and in this case, odd isn’t enough.