Photo: Rob Greig

From hundreds of feet above ground, London looks like a different city. Airy, green, calm. Hell, maybe even a bit clean. Seeing the city from this height makes you understand why there’s such a demand for high-rise living. There are currently more than 200 buildings of 20 storeys-plus proposed or being built in London. The vast majority of them will be luxury flats. Today’s elite long for the exclusivity of vertical living, the views and the glamour of the penthouse apartment. Who among us doesn’t secretly want to be a modern plutocrat, lording it over Manhattan with a tumbler of scotch in one hand and a cigar filled with the dried flesh of our enemies in the other?

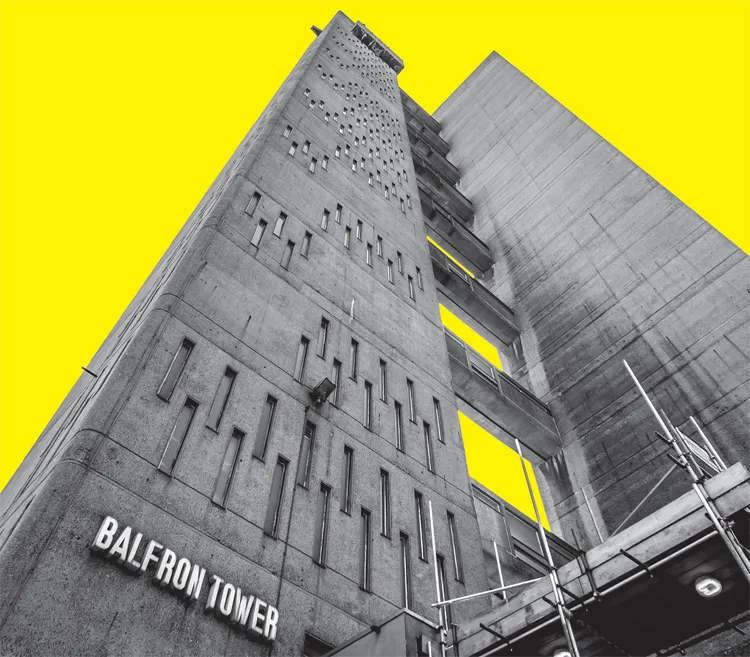

But this hasn’t always been what high-rise living in the city was like. Take a closer look at London’s residential skyline and you’ll notice two kinds of towers: new, shiny, glass-clad monoliths that most of us can’t afford to live in, and old, grim, grey, stubby tower blocks that most of us don’t want to live in. Sitting somewhere uncomfortably in between is Balfron Tower. Designed by Hungarian architect Ernö Goldfinger in 1963, this iconic modernist masterpiece is a big, looming, unmissably brutal chunk of architecture, originally built to house some of east London’s poorest residents. Today, however, it’s on the cusp of becoming one of the city’s most desirable bits of real estate. The history of the Balfron is more than a story of one building: it’s the story of how high-rise living has changed in London since the 60s.

The Balfron Tower. Photo: Lisa IndigoBurns Wormsley

I’ve cycled down the Limehouse Cut into the heart of Poplar to stand underneath the Balfron more times than I should admit, awed by its imposing presence. It’s a mean-looking thing: all grimy concrete and sci-fi geometricism. But there’s something beautiful about it. It’s stuck between an A-road near Canary Wharf, the black hole of the Blackwall Tunnel and the bleak greyness of the surrounding area, but 50 years after it was built, it still looks like something from the future. It doesn’t just impose itself on the landscape, it’s a cultural icon too, starring in films like ‘28 Days Later’, music videos by The Verve and Oasis, and countless gritty British TV shows. It’s also an important part of British architectural history: a socialist design in a brutalist style.

The Balfron was the first of two almost identical towers built in London by Goldfinger. The other, Ladbroke Grove’s Trellick Tower, is by far the more famous. Both were constructed to provide social housing for London’s workingclass communities. They were built with plenty of idealism in mind – these were hamlets in the sky (Balfron is a village in Scotland), vertical utopias where everyday Londoners could live in peace. Goldfinger and his wife even had a flat in the Balfron when the building first opened.

‘The Balfron is a classic piece of architecture of its time,’ says Peter Murray, architecture writer and chairman of New London Architecture. ‘It’s not just what it looks like, it’s actually the quality of the detailing, the solidity of the structure and the layout of the space.’ The flats themselves are huge. There’s privacy, too. The walls are thick and solid to keep sounds separated so you don’t feel stacked up among 100 other families.

Despite its architectural merits, the Balfron quickly became an unpleasant place to live. From the late ’60s onwards, reports of antisocial behaviour on the estate were rife – junkies in the stairwells, domestic violence, drug deals and constant low-level crime. How did those early ideals of community and social housing get smashed apart so easily?

Photo: Ben Scicluna

‘Like a lot of tall buildings, the Balfron was really badly managed,’ says Murray. ‘There was no proper control at the front door, families were put high up in the building and it gradually became a pretty nasty place to live in. It became a focus for vandalism, drug use and muggings.’ Things were the same over in west London at its sister building, the Trellick, which became so dangerous that Murray describes it as ‘pretty much a no-go area’. Apparently, people wouldn’t even go near it for fear of being hit by the stuff tenants would lob out of the windows.

But there was a turning point in west London in the mid-1990s, when residents of the Trellick came together to reverse the building’s fortunes. ‘What changed it fundamentally was right to buy,’ says Murray. ‘The mix of residents changed, and it gradually pulled itself up by its bootstraps. They got the borough to start funding repairs, then [the Trellick] got listed.’ It was private ownership that helped convert what had become a skyscraping slum into a building that everyone who’d ever worn a turtleneck was desperate to live in. With its mixture of social-housing tenants and private design anoraks, the Trellick today is a modernist success story.

The Trellick Tower. Photo: Lisa IndigoBurns Wormsley

The Balfron? Not so much. It went through the same period of violence and crime, but not the regeneration. Until now. Now a local housing association – Poplar HARCA – is starting to refurbish the flats in order to sell them on the open market. In the process, all social housing tenants have been moved out, and won’t be returning. There are currently no plans for social housing or flats with affordable rent in the Balfron. Considering the state of the housing crisis in London, it should come as no surprise that the plans have upset local residents. Action East End and Tower Hamlets Renters have actively protested outside of Poplar HARCA’s offices in recent months.

I talk to an artist called James, who has been living in the building for three years under a property guardianship scheme: ‘Until May 2014, when the majority of council tenants were rehoused, it was a very mixed community,’ he says. ‘Now it is mostly white, middle-class, early thirties. The character of the place has dissolved.’

A sign in the Balfron Tower lift. Photo: Bob Bob, Flickr

Peter Murray takes a rather different view: ‘To a certain extent, I think as long as other accommodation is provided in the area, it does often mean that these pieces of architecture are looked after rather better when they have private owners.’ Poplar HARCA tell me that ‘the aim is to reinvigorate Balfron Tower and create a building suitable for twenty-first-century contemporary living, giving it a new lease of life, while being sympathetic to the architectural heritage of this iconic building.’ In addition, the money from selling Balfron flats is intended to help fund social housing in the area. So while it’s not all bad news, it is a double-edged sword. The architectural significance of the building will be preserved, but in the process the building will become something far removed from what Goldfinger intended it to be. Design-centric living – which the architect envisaged for the everyday Londoner – will again only be accessible to the privileged few. ‘It’s scandalous,’ adds James. ‘If these flats are bought by overseas investors and then sit unoccupied, Ernö Goldfinger, a lifelong socialist, will be turning in his grave.’

Of the new high-rises in London, none has social housing in it. According to findings by housing charity Shelter, only 0.1 percent of London’s houses are affordable for the average young family. That’s just 43 homes. Wherever normal Londoners are going to be living in the coming decades, it probably isn’t in a penthouse. But whatever the Balfron’s future is, at least its status as a design icon is assured and its ragged, brutal outline will be inspiring design nerds like me for decades to come. If you have deep pockets, you could even own a slice of the tower yourself. Not that Goldfinger would’ve liked that very much.