On the nightlife scene

BEN BUCHANAN: There was a club called Club 57, which was when a group of people went to a church basement and they just put on shows for a couple hundred dollars. They did it three nights a week, films and art and just a mishmash of stuff. So [the owners of 'it' club Area] recreated that, and Area was like that idea, but on a big scale, $40,000 or $50,000 budget every six weeks or so. And they changed the whole interior to a theme. The theme could be night, sports, sex, the colour red, obelisks, fashion or whatever the theme was. And all the artists who were their friends... would come in and do stuff. And they would think it was fun because it was a cool place to come and join in. So it was a nightclub that ran four nights a week, all hours till 4 or 5 in the morning.

Unlike Studio 54, which was older people – and there just was not really much to look at at Studio 54, just flashing lights, disco music and a lot of cocaine – this was more arty. Feast your brain as well as your eyes and do all the same things you do in a club, but then you get nice things to think about and look at.

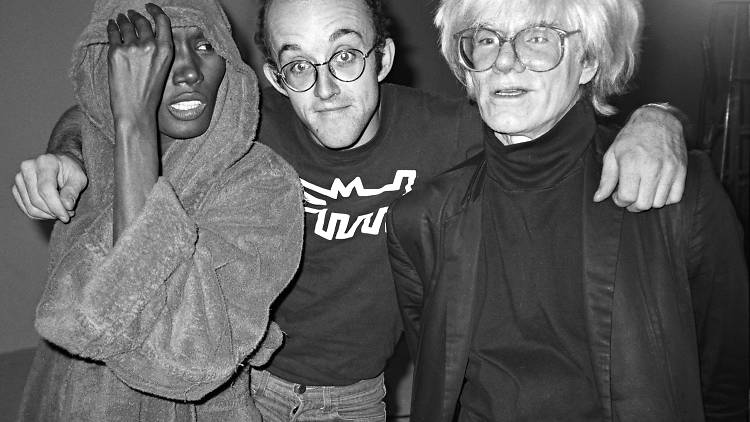

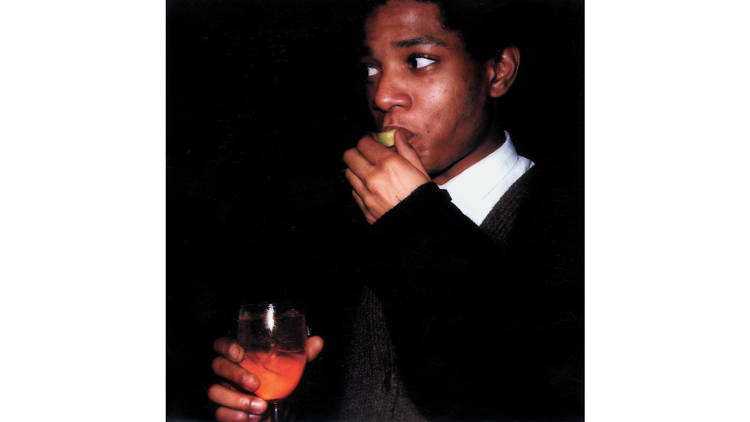

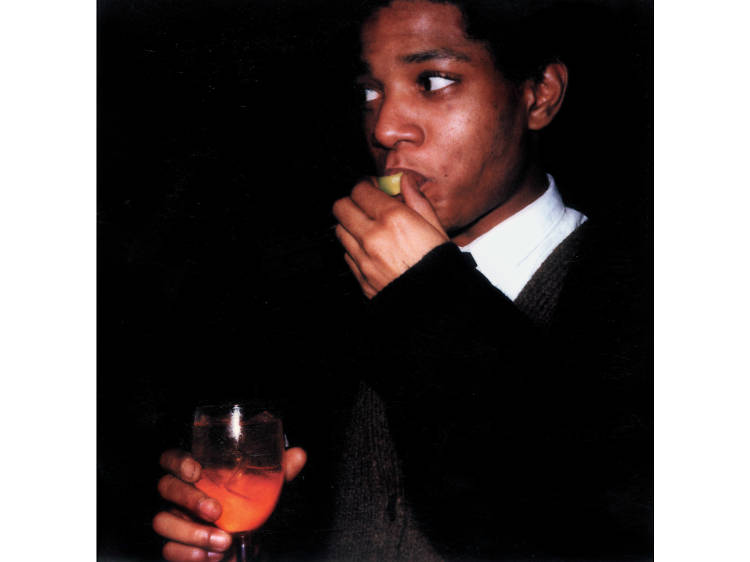

Basquiat used to bring his records and DJ in the lounge. He would just come in with a couple of crates of records and spend the evening playing records. He was an art star, we didn't pay him, he did it because he wanted to do it. So I have a lot of pictures of him doing that.

CARLO McCORMICK: Everyone kind of created their own opportunities outside the art world proper. So I worked at a club called Club 57.

Nightlife was a hugely important thing. New York had many thousands of clubs at that time. Right now it's got, in the whole city, like couple hundred or so. Then it was like 4,000 or something like that. New York was broke, totally bankrupt. It's just a hellish place. There was no money to be made, but nightlife was one of [ways to make money]. That and the porn industry, basically, we didn't have much left at that point – and dealing drugs. It was all pretty much shambolic, slightly criminal culture and economy.

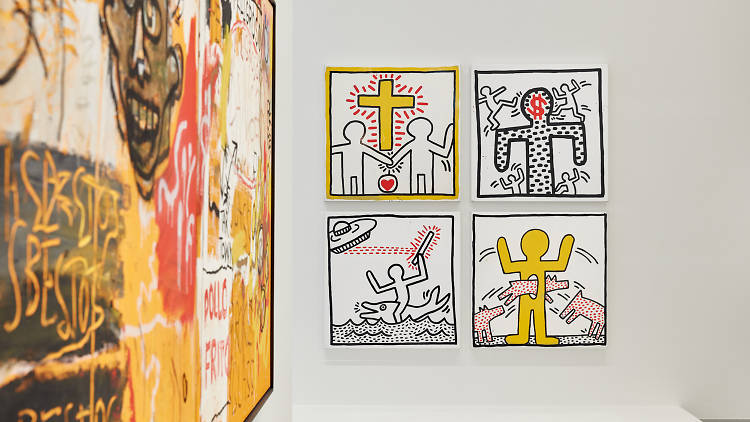

So the clubs were one, and obviously this kind of conversation that happened on the subways with graffiti art. Keith and Jean were very clear about, like, we're not graffiti artists. Not because they didn't like graffiti, they loved graffiti, but they didn't want to over-represent because they weren't like climbing fences and running from cops and jumping the third rail and learning these incredible mastery skills of what these people were doing with wild style lettering on the trains with aerosols. It was magic how this thing developed.

So that was one. And then the streets became another. And you can see both of these guys engaged the streets and the subways in their own way coming from studio practice ideas.