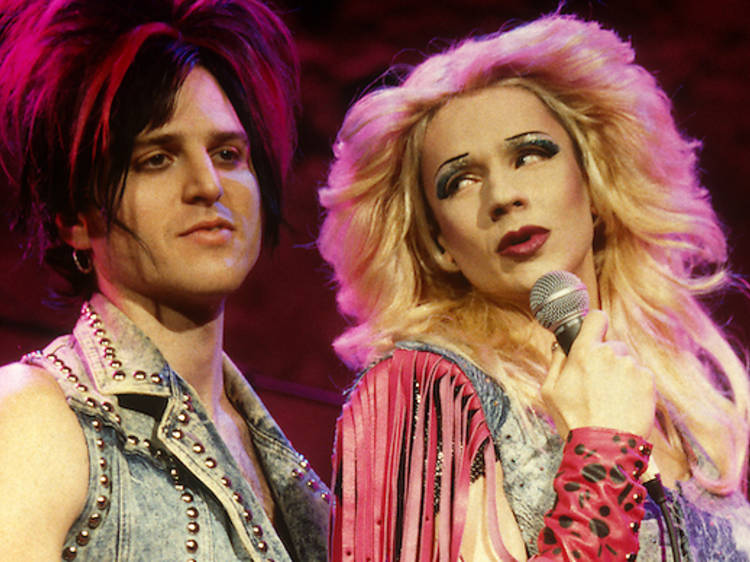

More than two decades after it blasted onstage at the Hotel Riverview in Greenwich Village, Hedwig and the Angry Inch retains its electric currency. Presented in the form of a concert by a defiantly vulnerable East German glam rocker named Hedwig—who landed in Middle America after a botched sex-change operation—the show has a wham-bam score by Stephen Trask (drawing on the sounds of ‘70s rockers like Lou Reed and David Bowie) and a witty, pained book by John Cameron Mitchell, who originated the title role (and took it over from Neil Patrick Harris in the musical’s 2014 Broadway revival). A headlong blast of queer energy, Hedwig is the ultimate antibinary musical, dissolving boundaries—between male and female, cis and trans, rock and roll and musical theater—in a messy, cathartic and ultimately joyful public struggle with questions of acceptance, control and self-love.

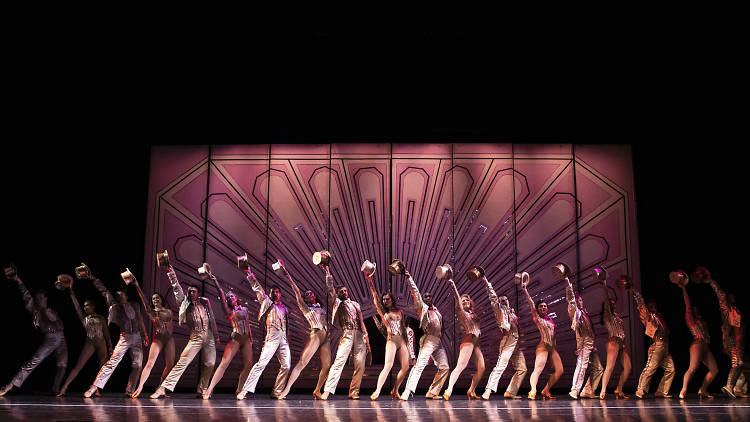

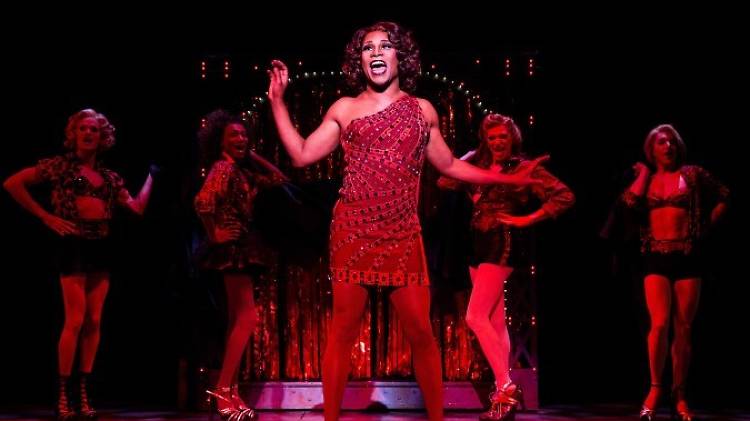

It is no secret that many LGBTQ+ people have a special affinity for Broadway musicals. "Keep it gay!" sings the flamboyant director in The Producers, and musical theater has long drawn nonstraight folks to the ranks of its creators, performers and fans. But it is only in the past fifty years or so that tuners have actually featured openly gay characters onstage—and the result has been some of the best Broadway shows of all time. Here is our list of the top musicals with strong gay themes, ranked for their combination of quality, historical importance and LGBTQ+ content. We've limited the list to ten, which means that some very good shows did not quite make the cut. But there's an awful lot here to be proud of.

RECOMMENDED: Complete A–Z listing of current Broadway shows