[category]

[title]

Driving Hong Kong from a sleepy fishing village to Asia’s World City, reclamation has shaped the very essence of our city. But as debate heats up over Chek Lap Kok’s third runway, Judd Boaz and Mark Tjhung dissect the land-sea debate and ponder how long we can continue developing our coastlines. Illustrations by Phoebe Cheng

The progression of reclaimed land in HK through history (Click for a larger image)

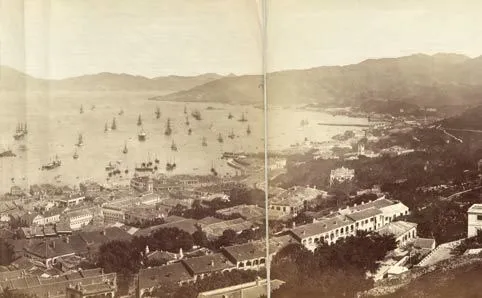

If you took a stroll along Hong Kong’s northern shoreline 170 years ago, your path would be very different to what it is today. Queen’s Road, without the trams rolling past, would be at the water’s edge, leading toward a Wan Chai, then known as the Praya East district, where Hennessy Road would be at the land’s boundary. Across Victoria Harbour, twice as wide as today, you might be able to make out the Kowloon Peninsula, a diminutive relation to its concrete modern manifestation, and beyond further, if you were to explore, you would find no Sha Tin, Tuen Mun, Tseung Kwan O or any of Hong Kong’s other numerous mainstay towns – in their place, a tranquil series of hills and valleys, rivers and endless sea. This was Hong Kong before reclamation.

The old Central shoreline

East Point and Causeway Bay, 1898

Indeed, modern Hong Kong is a reclaimed city. To put it into perspective, around 25 percent of all developed land in Hong Kong is built on reclaimed land. From the iconic Hong Kong skyline to the industrial hubs in the New Territories, reclamation has been a key element in turning Hong Kong from a tiny fishing village into a world city, transforming 67sq km of sea and swamp into prime real estate. But this reclamation has come at a steep cost. Little by little through piecemeal reclamation, Victoria Harbour has shrunk to half of its original size. Habitats have been destroyed across our coastlines, along with historical and cultural artefacts of old Hong Kong. With population growth pushing available land to its limit, the question that Hong Kong as a whole is grappling with is – where does it stop?

A history of reclamation

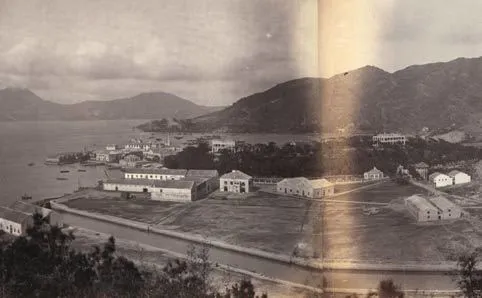

To really appreciate the role reclamation has played in the development on Hong Kong, and how it has helped the city develop from a population of just 7,450 in 1841 to the 7.2million it is today, it’s necessary to look back through its history. Although early attempts can be traced back to the Western Han Dynasty, land reclamation began in Hong Kong in earnest during British rule with the first reclamation of Bonham Strand in 1851. By promising waterfront companies the ‘ownership’ of any land they paid to have reclaimed, the government established a proper shoreline, and private money helped colour development policy for the better part of the next century. Indeed, as Hong Kong has developed, so its waterline has continued to retreat.

These early reclamation projects were created by cutting away large chunks of our mountainous terrain and dumping it into the sea, making both the more rugged terrain flat and the shoreline extend. Morrison Hill went into large portions of Wan Chai, Lam Tin’s Black Hill created parts of Kwun Tong and mud sourced from Ngau Tau Kok helped reclaim Kowloon Bay.

Taikoo reclamation, 1919-1920;

Image: John Swire & Sons Ltd. Courtesy of Historical Photographs of China

The massive influx of immigrants fleeing mainland China during the 1950s and 1960s, however, meant the government no longer had the luxury of waiting for businesses to reclaim piecemeal sections of land along the waterfront, and a new generation of satellite towns – Kwun Tong and Tsuen Wan in the 1950s and 1960s, and Sha Tin and Tai Po in the 1970s – were developed, each with an enormous emphasis on reclamation. With the overwhelming demand for new land, faster, more efficient and environmentally less dramatic techniques were developed in order to keep up. During the reclamation of Sha Tin during the 1970s, for example, the government used a low-cost dredging technique, pulling mud from the sea bed, allowing for land settlement, which ordinarily would have taken five to 10 years, to be achieved in just three months – the kind of new technique that allowed reclamation to increase at a steady rate.

Shatin reclamation, 1977; Image: Ko Tim-Keung

Western District reclamation, 1960s; Image: Ko Tim-keung

Yet as the new millennium closed in, the public attitude towards reclamation began to change – giving rise to new legislation in 1997 that would change the face of reclamation in Hong Kong.

The battle for the harbour

“In 1996 and 1997, reclamation sort of became a bad word with the legislation,” says Paul Zimmerman, CEO of Designing Hong Kong and an elected councillor in the Southern District representing the Pok Fu Lam constituency. The legislation in question is the Protection of the Harbour Ordinance, proposed by the Society for the Protection of the Harbour, an NGO founded in 1995. The Society fought for the legislation for two years and sent it to then Governor-in-Council Chris Patten alongside a petition with 148,041 signatures. It was finally passed by LegCo in 1997. The ordinance states:

“The harbour is to be protected and preserved as a special public asset and a natural heritage of Hong Kong people, and for that purpose there shall be a presumption against reclamation in the harbour.”

“It was perfect timing for the legislation,” says John Bowden of Save Our Shorelines, a Hong Kong-based NGO advocating protection of Hong Kong foreshores. “It was the end of the colonial era; it was Chris Patten enabling people to start thinking about what they wanted from a civil society and what they really felt like they wanted.” Winston Chu, one of the main proponents behind the legislation, aimed to protect the harbour, which he considers ‘the soul of Hong Kong’. Thus in many ways, harbour reclamation became the rallying cry for a new Hong Kong.

This manifested itself in various protests, none more noteworthy than in 2004, when the historic Edinburgh Place Ferry Pier and Queen’s Pier in Central were slated for demolition to make way for the Central harbour front reclamation (See HK's Top 10 Demplished buildings). Winston Chu says these losses can be attributed to Hong Kong people turning a blind eye to reclamation. “The funny thing about human psychology is they cannot visualise something before it happens. They say ‘oh, the government will not do that, the government will not do this’,” says Chu. “But when it really happens, then people got very excited and they started demonstrations. Then you have much support from the public, by which time it is too late.”

The reclamation works for the Central Harbourfront; Image: JO schmaltz

Indeed, heritage has been one of the concerns of those advocating against reclamation in various projects past. But perhaps the greater public outcry today has been focused on the increasing environmental impact that continued reclamation is having on the harbour.

The environmental alarm

Environmental concerns have long been an inevitable accompaniment to Hong Kong reclamation projects. And most recently, the discussion has focused on the impact of the proposed third runway for the Hong Kong International Airport, a project that aims to raise the airport’s flight-capacity by an extra 200,000 flights per year and which, with its proposed 650ha of reclaimed land, would make it Hong Kong’s second-largest reclamation ever. An Environmental Impact Assessment for the third runway was released on June 20 and closed for public consultation on July 19.

“[The reclamation] will cause some irreversible impacts to the marine environments,” says Samantha Lee, senior conservation officer, marine at WWF Hong Kong. “It will cause serious habitat loss, which is permanent.” In particular, Lee points to the risk to Chinese white dolphin – often known as the pink dolphin – as well as the fishing industry, with the government’s low-cost dredging technique of pulling up mud from the bottom of the sea to lay foundations increasing sediment in the water, making it turbid and drastically affecting fish populations. “This approach the government has been using is one of destroying first and conserving later,” says Lee.

The at-risk Chinese white dolphin

Many environmental activists share Lee’s views. “For a cosmopolitan society like Hong Kong, it’s quite ridiculous to reclaim the land where the Chinese white dolphins live. You can see the mindset of Hong Kong people and the government,” says Roy Tam, CEO of environmental group Green Sense. For Tam, the government has not been able to justify destruction of habitats and the deterioration of water quality that would occur with the third runway project. “If it’s an environmentally sensitive place like North Lantau, then we are definitely opposed to that,” he says.

Dr Li Kui-Wai, associate professor at City University of Hong Kong, however, says simply stopping reclamation on an environmental basis isn’t so cut-and-dry. “Obviously we would like to have cleaner areas and we want to have a better environment. But on the other hand, we are talking about the welfare of seven million people and the economic capabilities of Hong Kong. We have to strike a balance.”

But where does it stop?

Balance is a keyword in this debate – and with HK’s population projected to reach 8.47 million by 2041, there remains a tension between the need for land and the need to protect the environment.

In 2004, in the case of Town Planning Board v Society for Protection of the Harbour Ltd, the Court of Final Appeal laid out a four-headed public needs test to the continued reclamation of the harbour, which required several criteria to be met:

• that the development must address issues that affect Hong Kong in the present;

• that the development must serve an economic, environmental or social need of the city;

• that there must be no reasonable alternatives to the reclamation; and

• that the development must entail the very minimum level of reclamation to meet requirements.

Winston Chu sums up how he sees the test. “[The need for the reclamation] must be so overriding that the need is more important than the harbour,” he says. Indeed, there are those who suggest that reclamation purely for housing development may not even address the problem at hand. “Land created from reclamation is extremely expensive. If you make use of it for housing, the prices will always be very expensive and beyond people’s means,” says Chu. “As long as you do not develop the New Territories, there will not be enough land and the harbour will not be safe.”

The Real Estate Developers Association of Hong Kong said in a public submission to the government on proposed reclamation projects across Lantau Island in 2012, ‘we would recommend a proper balance to be adopted to avoid the public getting the impression that it is just reclamation for its own sake. Reclamation should only be considered as a last resort to create land for housing’, also noting that ‘the potential contribution [of reclamation] to regulating property prices is, at best, uncertain’.

Paul Zimmerman suggests that the answer lies in the New Territories, in the so-called ‘brownfield’ sites. “The key is to use the space that we do have in a more efficient way,” he says. “A lot of the industrial properties in the New Territories, for example, are totally space-inefficient.”

The clock is ticking on the government and Kenneth To can see the writing on the wall. “The government is scratching for odd pieces of land to meet the market,” says To, vice president of the Hong King Institute of Planners. “It won’t last long. Very soon you’ll be running out of those bits and pieces, and you really cannot increase density in the urban areas anymore. That’ll end in the next seven or eight years, at most.”

The future – and the government position

While there is significant opposition, as well as a clear call for balance from various environmental and business sectors, continued reclamation seems firmly on the government’s agenda. “For more than 100 years, Hong Kong has been producing land through reclamation, which proves to be an effective way of increasing land supply underpinning urban expansion,” wrote Secretary for Development Paul Chan this year. “The current land shortage is closely related to the sharp decrease in reclamation in the past decade.”

In a blog post on the Development Bureau website last year, Chan also stated: “Reclamation is the best way to build up a land reserve because it does not involve land resumption and rehousing, and the reclaimed land can be readily made available in the short, medium and long terms when the need arises... If Hong Kong remains hesitant and fails to expedite the relevant work, leaving the problem of land shortage to continue to hinder our livelihood and development, who will suffer most in the end?” Time Out contacted the Development Bureau, but it declined to comment.

As further evidence of the government’s drive to reclaim, in 2012, the Civil Engineering and Development Department produced a map (see above) flagging 25 potential sites for further reclamation, with several already in the early stages of planning. Kenneth To says this glut of proposals is a deliberate move to counteract opposition. “In the past few years, this government has been pushing the planners to identify more than enough development opportunities, knowing that many of them will not be able to go ahead,” he says.

Ultimately, the future of reclamation – its continuing drive into the harbour or otherwise – comes down to a precarious balancing act, and one where there are pros and cons to every outcome. While the government, with the pronouncements from the Secretary for Development, appears to have a clear position, the question for Hong Kong as a whole seems to be: where, in this precarious balancing act, does our collective conscience lie?

For more information on the current and future reclamation projects in Hong Kong, see devb.gov.hk. For more information on the proposed third runway, seethreerunwaysystem.com.

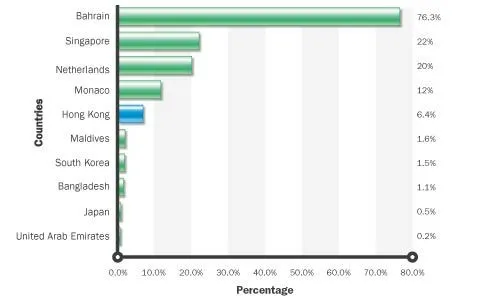

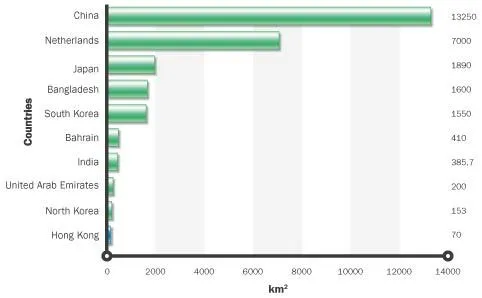

Reclamation around the world

Top 10 Countries with Most Reclamation by Percentage

Top 10 Countries with Most Reclamation by Area

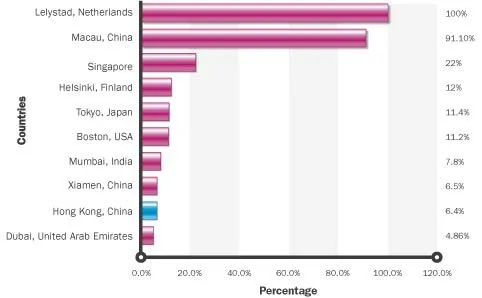

Top 10 Cities with Most Reclamation by Percentage

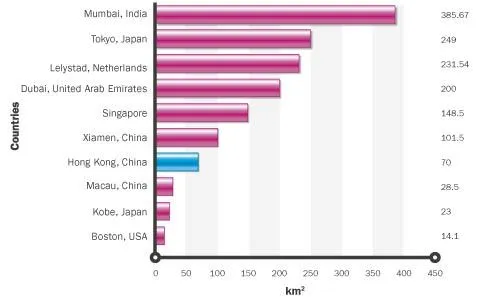

Top 10 Cities with Most Reclamation by Area

Discover Time Out original video