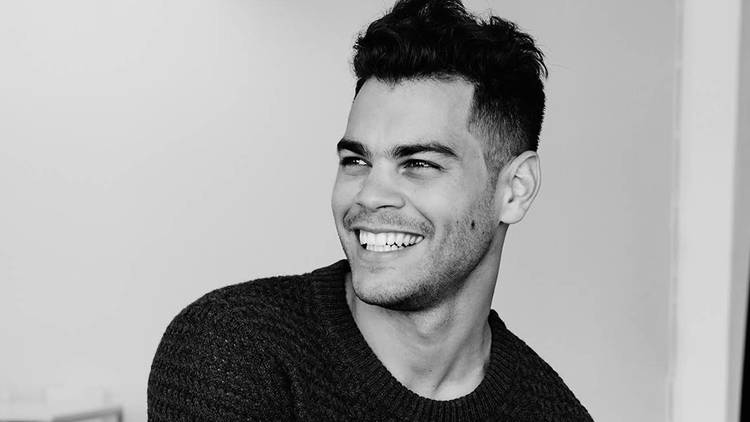

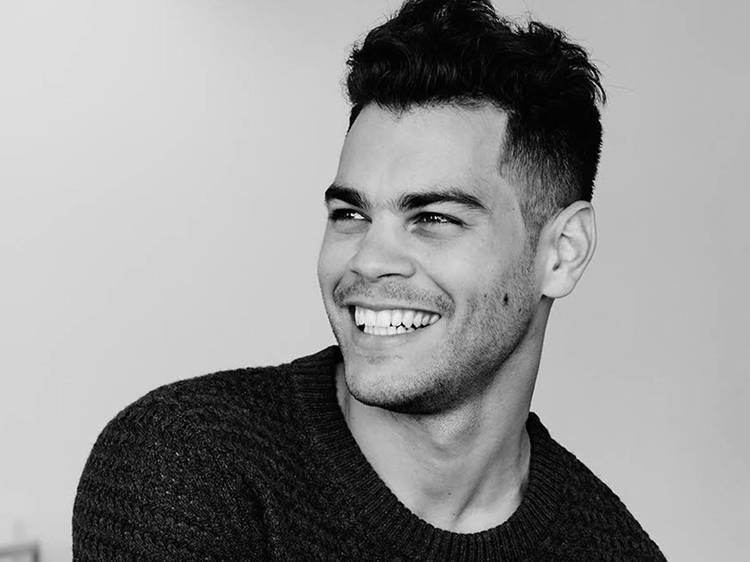

This month, Time Out Melbourne is co-edited by Jacob Boehme. Below, get to know the fiercely talented men and women making our city a deadlier place by shaping Melbourne’s future across many different fields.

Wominjeka. Welcome to the Deadly Issue and to our beautiful City of Melbourne. Like many Aboriginal peoples across our country, I wasn’t born or raised on my traditional lands of the Narangga and Kaurna nations in South Australia. I was born in the inner city suburb of Fitzroy, historically an important meeting place for many of our mob, and was raised on the other side of the river in Newport, on Kulin country, Bunjil’s country. I call Melbourne my home.

As creative director of Yirramboi First Nations Arts Festival, along with Yirramboi’s Elders, Blak Critics and the Time Out crew, we present for you a taste of Aboriginal Melbourne: its history and languages, and through our Deadliest Melburnians, a snapshot of the diversity and brilliance of local contemporary warriors shaping the economy and culture of the world’s most livable city.

This May we also celebrate National Reconciliation Week 2017 (May 27-June 3), which marks two significant milestones in the journey of a nation we now call Australia.

Fifty years ago, on May 27 1967, over 90 per cent of Australians voted to recognise us in the national census. Up until that point, we weren’t counted as citizens. For most of you reading this, that’s not that long ago – only one or two generations away.

The second significant milestone (June 3) is the 25th anniversary of the landmark Mabo decision, which legally recognised our relationship to country that existed prior to colonisation and that still exists today. We celebrate Uncle Eddie ‘Koiki’ Mabo’s well-documented and hard-won battle for our sovereign rights to land and country as First Peoples. And yet, the battle’s still not over. We stand on this day, and fight today, not only for our sovereignty but for the environmental futures of your children too.

Language and knowledge have power. Let these words empower you to listen to a place and know its story: one that carries the dreams of 1,000 generations who walked this land before you, and one that holds the talents and hopes of those that stand beside you. Jacob Boehme